“Debsian socialism” remains in the American lexicon as a vestige of the golden age of socialist popularity, and for good reasons. Debs’s near-million-vote total in the presidential election of 1912 would have rendered the Socialist Party the “third party” in American politics, if the Progressive “Bull Moose” Party, which split from the Republicans under the leadership of Theodore Roosevelt, had not offered overpowering competition. For a few years before and after, socialists held hundreds of offices in many states outside the South (and some even there), along with a few elected representatives to Congress. The socialist cause seemed to be growing ever more powerful—until the United States entered World War I in 1917. Everything about this success story, however limited in time, is connected with Eugene V. Debs.

How did historical developments pave the way for socialist influences? The nation grew more prosperous, fast becoming a global economic leader, but only through “boom-and-bust” cycles, leaving millions in abject poverty during downturns. Industry advanced, but accelerating mechanization replaced the well-paying skilled jobs established only a generation or two earlier. New floods of immigrants, overwhelmingly from Eastern and Southern Europe, offered employers low-wage opportunities to get rid of costlier and sometimes more resistant workers. Smaller farmers in the West and South, especially, suffered from advances in large-scale agricultural production and distribution that left them behind or, worse, trapped them in tenant-farmer status. Meanwhile, the intimacy of small-town and rural life seemed to grow more distant as fewer people depended upon homegrown crops and household skills. Nostalgia flourished in the young nation—and turned bitter.

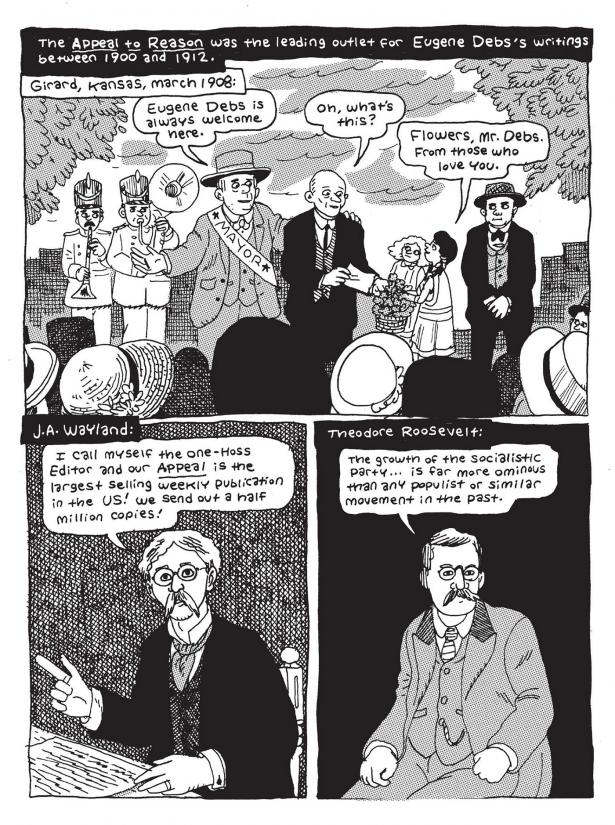

The largest conglomeration of socialists, middle-aged and middle American, bore little superficial resemblance to the socialist proletarians of Europe. Foreign visitors and even New Yorkers could hardly understand that the Appeal to Reason, the nation’s largest weekly political newspaper, came from small-town Kansas. A later study of the “Appeal Army,” the volunteers who sought new subscribers, revealed a mostly middle-aged cadre, a combination of craft workers, small farmers, and ministers’ wives—the very social types sometimes ridiculed by European Marxists. But they educated themselves, built local socialist chapters, and often published their own local newspapers.

They also got votes, up to a point. The presidential vote for Debs rose from 88,000 (in 1900) to 400,000 (in 1904), 420,000 (in 1908), and 900,000 (in 1912)—proportionately strongest in Oklahoma until the approach of the world war. Debs’s campaigns had special strength in more than a dozen German American districts, with Milwaukee in the lead, and became increasingly strong among Jewish voters in New York as the years passed. By 1912, more than 75 socialist mayors presided in 23 states, the largest number in the small industrial towns of Ohio, alongside three Christian socialist ministers. Even in the Deep South, socialist candidates ran strongly in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Foreign-born workers and their families who were drawn to socialist ideas (or brought such ideas over from the Old World) also seemed to adore, even worship, Debs, even more than the native-born. They feared prejudice along with class oppression, and Debs offered them hope and direction. A 97-year-old Slovenian woman and former hat makers’ union leader, interviewed in 1981, recalled with excitement, “Gene Debs held my baby!” She held that memory dear.

Edited excerpt from Eugene V. Debs, A Graphic Biography (Verso Books, 2019) appears by permission of the publisher. Art by Noah Van Sciver, script by Paul Buhle and Steve Max, with David Nance.

No Paywall. No Ads. Just Readers Like You.

You can help fund powerful stories to light the way forward.

Donate Now.

Spread the word