A 30-second search on the internet produces at least two dozen stories from U.S. newspapers and other media about San Pedro Sula in Honduras. “Honduran City is World Murder Capital,” announces Fox News. Business Insider calls it “the most violent city on earth.” In an attempt to explain the motivation for migrant caravans traveling to the U.S.-Mexico border, NPR labels it “one of the most violent cities in the world.”

This wave of media attention has been going on for at least half a decade, as tens of thousands of Hondurans arrive at the border seeking refuge. President Trump’s rhetoric portraying the caravans as a threat has focused even more attention on this Honduran city.

Fear of violence is a completely legitimate reason for leaving home and making the dangerous journey north. Violence and gangs, however, are often presented by U.S. media as the only explanation for the exodus of Hondurans from this metropolis. Yet more than a century of history connects the city with the United States, in a close but unequal, and usually abusive, relationship, at least for Hondurans.

Over that time, San Pedro Sula has been the capital of banana exports, a city wracked by war and death squads, and a factory town for the garment industry. Most recently, it has become a community hit by deindustrialization as hard as any textile town in New England. The media almost always ignores this history, yet it is this long relationship that has produced the migration with which the media seems obsessed.

That “murder capital” narrative, however, is being challenged increasingly by U.S. organizations calling for a deeper look. Some of them started as defenders of migrants incarcerated in U.S. detention centers, and now seek to clarify the root causes of migration as a way to support migrants and their home communities.

A recent four-page spread in The New York Times Magazine described in detail the lives of young people in San Pedro Sula’s Rivera Hernández neighborhood. Its author, Azam Ahmed, explained to readers that he wanted to “bear witness,” “to capture just how inescapable the violence was,” in the context of “tens of thousands fleeing the region.” Honduras’s state of crisis, he wrote, is a result of “warring gang factions.”

Accompanying the article were Tyler Hicks’s dark photographs of gang members, their faces wrapped in bandannas, one holding his gun loosely by his side. Both text and images present these young people as the “other”—a vision to frighten comfortable middle-class readers with what seems an inside look into an alien and violent world.

The Times piece is only the latest of many that paint this picture. Four years ago, Juan José Martínez D’Aubuisson wrote an even longer article about the same neighborhood. Pastor Daniel Pacheco arranged the meetings with the gangs, as he did for Ahmed and Hicks. That article, appearing in InSight Crime, concluded: “The violence here is difficult to understand. ... The people live with the violence without thinking about it, like how the Eskimos spend their days without thinking about the snow that surrounds them.”

Steven Dudley, InSight Crime’s co-founder and a former bureau chief for the Miami Herald, at least acknowledged the link between violence in San Pedro Sula and U.S. deportation policy. “Gangs’ emergence in the mid-1990s,” he wrote in another article, “coincided with state and federal initiatives in the United States. ... The number of gang members deported quickly increased, as did the number of transnational gangs operating in [Central America]. ... With the deportations, the two most prominent Los Angeles gangs—the Mara Salvatrucha 13 and the Barrio 18—quickly became the two largest transnational gangs.”

Some 129,726 people convicted of crimes were deported to Central America from 2001 to 2010, 44,042 to Honduras. U.S. law enforcement pressured local police in the region to adopt a “mano dura,” or hard-line approach to them. Many young people deported from the U.S. were incarcerated as soon as they arrived. Prisons became schools for gang recruitment.

The Trump administration argues today that violence is not a basis for an asylum claim by refugees at the border, but this and previous U.S. administrations have cited that violence as a threat to Americans. When Marine Corps General John Kelly was commander of the U.S. Southern Command under President Obama, before his stint in the Trump White House, he framed Central American migration as a national-security threat, calling it a “crime-terror convergence.” And the gangs and violence became a justification for U.S. funding of the Central American Regional Security Initiative, which supplied $204 million to the corrupt Honduran government for army and police in 2016-2017, and another $112 million for economic development.

There is indeed violence in San Pedro Sula. But that violence has a long history, and is intimately tied to the city’s relationship with the U.S. That relationship is so close that the most basic decisions affecting the lives of its residents have often been made by powerful Americans.

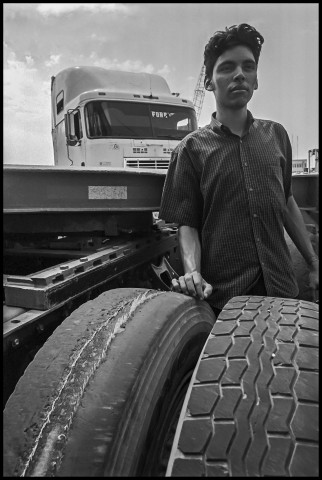

A young driver of a rig bring down goods from the San Pedro Sula factories shows that the tread on his tires has worn so thin that the metal belt is exposed. David Bacon

The first was Samuel Zemurray, who founded the Cuyamel Fruit Company, and eventually became the head of United Fruit (which we know today as Chiquita Banana, or formally, Chiquita Brands International). A Russian immigrant who settled in New Orleans, Zemurray started as a banana importer in 1898, and then in 1910 bought 5,000 acres along the Cuyamel River, near the small town of San Pedro Sula, which he made the headquarters of his banana empire.

When the Honduran government wouldn’t give him land concessions and low taxes, Zemurray hired mercenaries, Guy “Machine Gun” Molony and Lee Christmas. In 1912,they overthrew the president, and installed Manuel Bonilla in his place. Zemurray developed the port of Puerto Cortes, 30 miles from San Pedro Sula on the Caribbean coast, to handle his cargo, and a railroad to connect them. He ruled every aspect of the lives of the people in the region, leading the U.S. embassy to call his holdings “a state within another state.”

Successive Honduran governments protected Cuyamel, and, in its later incarnation, United Fruit. Banana workers organized a strike in 1920, and the U.S. sent a warship to put it down. In 1932, General Tiburcio Carías Andino outlawed strikes, and for good measure, the Honduran Communist Party. Despite the repression, however, Hondurans organized one of the most active labor movements in Central America, starting on the banana plantations.

Zemurray became known as the “banana king,” with huge investments throughout Central America backed by Lehman Brothers and Goldman Sachs. In U.S. politics, Zemurray was a liberal, supporting the New Deal and even The Nation magazine. His investments were threatened, however, when Jacobo Arbenz was elected president of Guatemala in 1951, promising land reform. Zemurray then hired pioneering public-opinion manipulator Edward Bernays to convince the U.S. Congress that Guatemala had become a Soviet “threat,” and Arbenz was overthrown in a CIA-orchestrated coup.

A succession of generals governed Honduras from 1963 to 1981, taking bribes from United Fruit and tolerating the growing drug trade. At the end of that period, during the presidency of Ronald Reagan, the United States began using the country as a base to fight to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua, and to train the Salvadoran army to defeat the Farabundo Marti Front for National Liberation (FMLN) in El Salvador’s civil war.

Honduras had its own small guerrilla movements, like the others challenging landed elites and their U.S. partners throughout the region. In September 1982, leftist guerillas took 100 businessmen and government officials hostage for eight days in San Pedro Sula. For its part, the government sponsored death squads in San Pedro Sula and Tegucigalpa. U.S. Senator Tom Harkin accused the CIA and U.S. military advisers of organizing Battalion 316, which was responsible for murdering and “disappearing” more than 150 leftists and trade unionists from 1981 to 1984, one of them an American Jesuit priest, James Carney.

The point person for U.S. policy in Honduras was Ambassador John Negroponte, who’d been a political officer in Vietnam during the Vietnam War. According to a 1982 Newsweek article by John Brecher, John Walcott, David Martin, and Beth Nissen, “Negroponte forged close ties with powerful Hondurans, especially the commander of the armed forces, Gen. Gustavo Adolfo Alvarez. ... ‘They discuss what should be done, and then Alvarez does what Negroponte tells him to,’ a member of the military high command said matter-of-factly.”

Hondurans didn’t accept these policies passively. Some 40,000 people demonstrated in San Pedro Sula against the U.S. “contra war” in next-door Nicaragua, and another 60,000 in Tegucigalpa. Opposition grew so strong that after elections were re-established, President José Azcona Hoyo ordered the “contras” to leave in 1988.

As the Central American wars ramped up, Honduras opened its first industrial free-trade zone in 1976. Beginning in the late 1980s after the wars ended, the U.S. Agency for International Development initiated a large program to develop export processing zones in San Pedro Sula.

USAID financing paid for road construction, sewers, buildings, transportation, and the basic infrastructure for manufacturing. U.S. companies were then wooed to either invest directly in building plants themselves, or guaranteeing work to contractors to operate factories for them. By the 2000s, the country had become the fifth-largest exporter of clothes to the United States, and the biggest in cotton socks and underwear. That production was concentrated in San Pedro Sula, which became the industrial heart of Honduras. The goods were shipped out through Puerto Cortes.

Carol Vasquez, daughter of Hector Vasquez, an owner-operator and leader of job actions by the Honduran port truckers’ union. David Bacon

San Pedro Sula became a factory town. Lining its main arteries were roughconcrete buildings housing enterprises that sewed garments, packed shrimp, or ran injection molding machines churning out plastic parts. At shift change, young women streamed through the gates, while men piloted the trucks carrying containers of merchandise to the nearby docks in Puerto Cortes.

One of San Pedro Sula’s workers, Claudia Molina, came to the U.S. in 1995 to describe conditions in the plants. “Our work day is from 7:30 a.m. to 8:30 p.m.,” Molina told me in an interview, “sometimes until 10:30, from Monday to Friday. On Saturday we start at 7:30 a.m. We get an hour for lunch, and work until 6:30 p.m. We take a half hour again to eat, and then we work from 7 p.m. until midnight. We take another half hour rest, and then go until 6 on Sunday morning. Working like this I earned 270 lempiras per week [about $30 at the time].”

Molina worked for a company, Orion, that sewed garments for big U.S. clothing lines. On June 10, 1995, a company security guard shot a worker three times in the head. He’d gone into the plant without an ID card to collect his paycheck. Workers stopped work. “We demanded that the company give the worker’s family the pay they owed him, and that they recognize our union,” Molina recalled. Instead, Orion fired more than 600 people.

Many factories had a company doctor to see to it that workers didn’t qualify for disability payments, she charged. As well, the U.S.-owned companies in San Pedro Sula were intensely preoccupied with the sex lives of young women workers. At Orion, the doctor handed out contraceptives. Distribution of birth control pills in factories was not motivated by a concern for the reproductive rights of the women workers, however, but by the companies’ desire to keep women working on the production lines.

Price Waterhouse, the large U.S. accounting firm, got two U.S. government contracts to evaluate USAID programs, and to identify problems hindering the growth of the plants in San Pedro Sula. These studies, in October 1992 and May 1993, identified the main problem faced by employers as a potential labor shortage, which would exert an upward pressure on wages. Fifty factories in Honduran free-trade zones employed 22,342 workers by March 1992. Price Waterhouse predicted that 287 factories would soon employ 105,000. Consequently, “EPZ’s labor demands could not be met by natural population growth.” The most important way to solve labor needs, it said, was through “an increase in the labor participation rates of young women,” that is, by drawing more young women into the workforce and keeping them there.

At the time, women made up 84 percent of the workforce in Honduran maquiladoras, over 95 percent of them younger than 30, and half younger than 20. They were at the point in their lives where most wanted to begin their own families. Price Waterhouse noted with disapproval that “the pregnancy rate among women of childbearing age was 4 percent in June 1992, up from 2.5 percent six months earlier. This is regarded as too high (3 percent would be the maximum acceptable).”

To keep women from getting pregnant and leaving the factory to have children, USAID funded the Honduran Association for Family Planning, which established “contraceptive distribution posts staffed by nurses in three EPZ factories: Monty, and Hanes … and MAINTA (OshKosh B’Gosh).” As the companies began to run out of girls in their late teenage years, younger and younger girls were drawn into the plants. One study featured a table showing that children between 10 and 14 made up 16 percent of the women either employed or seeking jobs. A footnote claimed “the legal minimum working age in Honduras is 15, but in the rural economy it is normal to work from ten onwards.”

In 2005, the U.S. and Central American governments negotiated a free-trade agreement to protect the rights of foreign investors in economies based on exports to the U.S. When the Central America Free Trade Agreement came up for a vote in the U.S. Congress, supporters claimed it would produce jobs in maquiladoras and slow down migration. Honduran social movements wouldn’t drink the Kool-Aid, however. When the Honduran Congress took up ratification, more than a thousand demonstrators filled the streets of Tegucigalpa, angrily denouncing the treaty. After the Congress ratified CAFTA anyway, the crowd was so angry that terrified deputies fled.

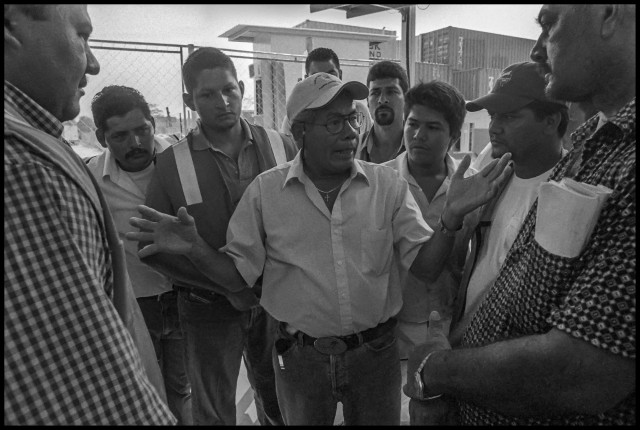

Erasmo Flores, president of the union for Honduran port truckers, talks with drivers and union members about their workplace problems. David Bacon

“We chased them out, and then we went into the chambers ourselves,” said Erasmo Flores, president of the Sindicato Nacional de Motoristas de Equipo Pesado de Honduras (SINAMEQUIPH), the union for the port truckers of San Pedro Sula and Puerto Cortes, in an interview. “Then we constituted ourselves as the congress of the true representatives of the Honduran people, and voted to scrap Congress’s ratification.” While admittedly an act of political theater by the left-wing Bloque Popular, the protest showed how unpopular the agreement was in Central America among workers and farmers—those people most likely to become migrants.

In November of that year, progressive Honduran parties finally elected a president, Manuel Zelaya, a rancher in a cowboy hat. They couldn’t stop implementation of CAFTA, but Zelaya announced a program of economic and social reforms, including raising the minimum wage, giving subsidies to small farmers, cutting interest rates, and instituting free education. All of these were measures that, by raising living standards, would have given people a future at home in Honduras. But in 2009, Zelaya was overthrown by the military and put on a plane out of the country. After a weak protest, the Obama administration gave de facto approval (and more military aid) to the coup regime that followed.

If the social and political change that Zelaya was beginning had been allowed to continue, fewer Hondurans would be trying to come to the U.S.

CAFTA also required privatization of state-owned assets to create investment opportunities for foreign corporations. Honduras’s General Union of Dock Workers twice beat back government efforts to privatize the docks of Puerto Cortes, mobilizing the whole town in the process. “We put our union’s assets, like our soccer field and clinic, at the service of the town,” said Roberto Contreras, a union officer and Honduran representative for the International Transport Workers’ Federation, in an interview. “When the government tried to privatize our jobs, we told people that if we didn’t cooperate to defeat it, the whole town would lose, not just the port workers.”

Despite this opposition, the coup government that replaced Zelaya finally did privatize the shipping terminals in Puerto Cortes in 2013, and gave a contract to a company from the Philippines, ICTSI, to run them. As an incentive, it gave the company the freedom to fire workers who belonged to the union. When dockworkers saw newly hired laborers in jobs they’d done for generations, they protested. The government sent in the army and arrested 129 of the protestors, charging them with “terrorism.” Attackers broke into the home of the union’s general secretary, Victor Crespo, and a truck mysteriously hit and killed his father in front of their home. Crespo had to leave the country.

By 2006, San Pedro Sula had half a million inhabitants, working in more than 200 factories. By 2011, it was generating two-thirds of Honduras’s GDP. Nevertheless, the country remained one of the poorest in Latin America, with the greatest income inequality. Hurricane Mitch had already devastated the banana plantations in 1998. Garment production began to decline after the U.S. recession hit in 2008, and plants relocated to countries where labor costs were even cheaper.

According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, the coup against Zelaya and the U.S. recession had devastating impacts on Hondurans. The post-coup government of Porfirio Lobo reduced social spending. By 2012, 66 percent of Hondurans lived in poverty, and 46 percent in extreme poverty. Unemployment went from 6.8 percent in 2008 to 14.1 percent in 2012, while the number of people working full time for less than the nation’s minimum wage (86 cents per hour in 2014) went from 28.8 percent to 46.3 percent.

As a migration-preventing strategy, CAFTA and the poverty-wage economic model imposed on San Pedro Sula was a bust. In 2014, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended 90,968 Honduran migrants at the border. That number fell in 2015 to 33,445, and then went up to 52,952 in 2016 and 47,260 in 2017,when the number of people detained while traveling with children reached 39,439.

Blaming the wave of migration on violence, however, is too simple. From 2011 to 2017, the number of killings in Honduras actually dropped, from 87 per 100,000 to 44. Pastor Daniel Pacheco told Los Angeles Times reporter Kate Linthicum, “I can ask them to leave the gang, but I don’t have anything else to offer them. Even if they graduate high school, they can’t get a job.”

Soon, going to school, or getting medical attention for their injuries, will become more difficult. On May 2, Radio Progreso in San Pedro Sula exposed an agreement between the Honduran government and the International Monetary Fund calling for cuts in the budget for education and health care.The story predicted that cuts will include the firing of teachers and health-care workers and less money for buying medicine.

The IMF, in which U.S. representatives often decide policy, demanded that the government hand over administration of public hospitals to private foundations, and that it privatize the state-owned electricity and telephone companies. Radio Progreso noted that “these enterprises are experiencing firings and the reduction of their budgets.”

Longshoremen load a container of goods from San Pedro Sula factories onto a ship bound for the U.S. David Bacon

Conditions for women still working in San Pedro Sula’s factories have deteriorated as well, leading the Collective of Honduran Women to organize an Occupy-style “planton,” or encampment, on May Day. The group denounced the government for approving rising production quotas, “in which supervisors stand behind the workers with a stopwatch to time their movements. They prohibit them from leaving the line to go to the bathroom, much less get a drink of water, because they must continue working.” The collective charged that women as young as 22, 25, or 30 are already incapacitated by carpal tunnel syndrome.

The government’s cuts were met throughout May by mass protests, including highway blockades by teachers and health workers. Police used teargas against demonstrators, some of whom were wounded by gunshots and others detained. In Tegucigalpa, teachers began a national strike on May 30 with a march by 20,000 people. The tear- and pepper gas used by police against the demonstrators was so intense that it closed the international airport.

The government signing the agreements with the IMF is headed by Porfirio Lobo’s successor as president, Juan Orlando Hernandez, who has continued the policies of rolling back Zelaya’s reforms. Last year, U.S. prosecutors charged the president’s brother Tony Hernandez with transporting cocaine through Central America in cooperation with government officials. The drug trade that counts in Honduras, it seems, isn’t the one in the Rivera Hernández barrio.

Defying the Honduran Constitution’s ban on re-election, Hernandez held on to power in 2017 in a contest marked by allegations of widespread fraud. The left’s candidate, Salvador Nasralla,was leading in the polls, and Honduras’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal called his lead “irreversible.” Then the computers counting the ballots mysteriously went down, and a day later Hernandez claimed he’d won. Widespread protests followed, and Hernandez declared a state of emergency limiting the right to assemble. According to Radio Progreso, at least 1,351 people were arrested.

The Unitarian Universalist Service Committee (UUSC) sent a delegation to Honduras to take testimony on the election and ensuing protests, and found that the Honduran National Police, and special units of the security forces, the Cobras and the Tigres, had beaten and tortured people. The U.S. military has trained all three.

The UUSC and other groups with ties to progressive movements in San Pedro Sula are supporting a bill in the U.S. Congress, HR 1945, introduced by Democratic Representatives Hank Johnson, Jan Schakowsky, Jose Serrano, and Marcy Kaptur. The bill would suspend U.S. military aid and discourage loans from international development banks until the Honduran government prosecutes those guilty of human rights violations.

U.S. unions have also sent delegations to Honduras to investigate the root causes of migration. In 2014, AFL-CIO Executive Vice President Tefere Gebre led one such group and in early 2015 produced a widely discussed report on its return. “What we witnessed,” he said, “was the intersection of our corporate-dominated trade policies with our broken immigration system, contributing to a state that fails workers and their families and forces them to live in fear.” The report, “Trade, Violence and Migration: The Broken Promises to Honduran Workers,” was unusually critical of U.S. foreign and immigration policies. It demanded that the U.S. extend refugee status to people, especially children, fleeing violence and persecution, and end the mass detention of migrants. It supported “trade policies that lead to the creation of decent work,” and “ending all aid to the military.”

Recently, another labor delegation was led by President Stuart Appelbaum of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. It focused on violence against unions and workers. “Gang violence is a result of economic insecurity and high poverty,” Appelbaum said in an interview. “Unions and workers fighting for their rights are victimized by the same violence, and by government sanction of it.”

U.S. immigration policy makes a major distinction between migrants who claim refugee status based on their fear of persecution and so-called economic migrants who flee poverty and hunger. Yet for many people leaving San Pedro Sula, this is a distinction with no difference. People leave home because staying becomes untenable, often for a combination of reasons. They flee from the violence. They leave because they were laid off as teachers or nurses, or because they couldn’t get an education for their kids or medical care in a hospital.

The Pew Research Center reports 96 percent of Hondurans deported from the U.S.say they migrated because of grinding poverty. Even if you don’t fear being beaten or murdered, you still don’t want to die poor and hungry.

But the reality is also that people don’t want to leave. Even the gang members interviewed by Azam Ahmed say they don’t intend to leave San Pedro Sula: “But the surviving members of Casa Blanca,” he writes, “who once numbered in the dozens, do not want to flee, like tens of thousands of their countrymen have. They say they have jobs to keep, children to feed, families, neighbors and loved ones to protect.”

They are, as Reverend Deborah Lee of the Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity, who has led several faith-based groups to Honduras, says, “fighting to stay home.” That perspective gives her a deeper insight into the lives of people in San Pedro Sula than the stereotype of “murder capital of the world.” She says that the purpose of her investigation and documentation, and of her political activism, isn’t to stop migration. It’s to stop its forcible nature, and give people a choice. She was one of the architects of the three declarations of faith that her organization has put forth. “We envision a world where migration is not forced,” it says, and where it is not criminalized. “We defend migration as a choice for self-determination and a life free from violence and insecurity.” And finally, this vision recognizes history. “We must bear responsibility for our role in the root causes driving forced migration, and support those for whom it is too late.”

Reverend Lee’s delegations arose from a seven-year campaign to force the closure of the jail holding immigrants for deportation in Richmond, California. In the course of many vigils and demonstrations, her group formed relationships with imprisoned Central American migrants in the detention center, which led them to question why people had left their homes to begin with. Eventually, they found themselves looking at San Pedro Sula’s long relationship with the U.S.

The vision directly contrary to Lee’s—the nativist vision—was on display a few years ago, when buses carrying immigrant children in detention rolled into Murrieta, California, and were met by nativist protesters. One waved a sign reading, “Send them back with birth control!”

But the U.S. had already tried that, in its San Pedro Sula factories.

David Bacon is a California writer and photojournalist; his latest book is In the Fields of the North / En los Campos del Norte (University of California / El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, 2017).

Read the original article at Prospect.org.

Used with the permission. © The American Prospect, Prospect.org, 2019. All rights reserved.

Support the American Prospect.

Click here to support the Prospect's brand of independent impact journalism

Spread the word