Some of America’s most notorious racist riots happened 100 years ago this summer. Confronting a national epidemic of white mob violence, 1919 was a time when black people in the United States defended themselves, fought back, and demanded full citizenship through thousands of acts of courage, small and large, individual and collective.

But pull a standard U.S. history textbook off the shelf and you’re unlikely to find more than a paragraph on the 1919 riots. What you do find downplays both racism and black resistance while distorting facts in a dangerous “both sides” framing. These textbooks render students stupid about white supremacy and bereft of examples from those who defied it.

At this moment of revived racist backlash, all of us need to learn the lessons of 1919.

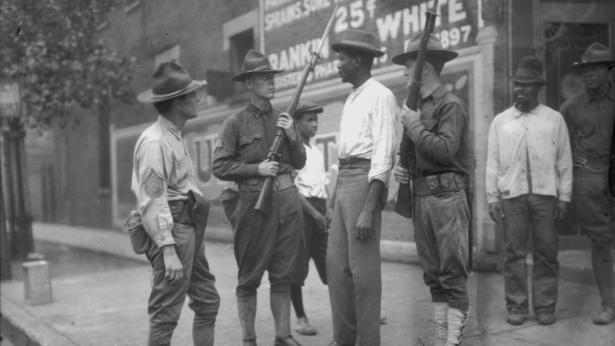

Throughout 1919 the exercise of black agency — black veterans wearing their military uniforms in public, black children swimming in the white section of Lake Michigan, black sharecroppers in Arkansas organizing for better wages and working conditions — was met with white mob terror. A wave of anti-black collective violence usually and problematically termed “race riots” occurred in Charleston, South Carolina; Longview, Texas; Bisbee, Arizona; Washington, D.C.; Chicago; Knoxville, Tennessee; Omaha, Nebraska; and Elaine, Arkansas. In addition, white supremacists lynched nearly 100 black people and initiated dozens of smaller racist clashes throughout the country in 1919. In Pittsburgh, the Klan made clear the goal of this bloody work in the printed notices posted around a black neighborhood: “The war is over, negroes. Stay in your place. If you don’t, we’ll put you there.”

Red Summer — so deemed by NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson to capture its sheer bloodiness — is a study in what historian Carol Anderson calls white rage. In White Rage: the Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, Anderson writes, “The trigger for white rage, inevitably, is black advancement. It is not the mere presence of black people that is the problem; rather, it is blackness with ambition, with drive, with purpose, with aspirations, and with demands for full and equal citizenship.” According to historian David Krugler, the official death toll of 1919’s epidemic of white rage exceeded 150. ”The majority of the victims were black,” he wrote, “Yet African Americans refused to surrender.”

In Knoxville, Tennessee, armed black men organized themselves to successfully repel hundreds of white rioters who had already destroyed the county jail with a battering ram and dynamite. In Chicago, African-Americans formed self-defense units after days of white terror in their neighborhoods. Many of these defenders were veterans, among the 370,000 black men inducted into the Army during World War I who hoped fighting for democracy abroad might finally secure their first-class citizenship at home. The mob violence in Chicago convinced Harry Haywood, a veteran of the all-black 370th Infantry Regiment, he’d made a mistake. As he explained, “I had been fighting the wrong war. The Germans weren’t the enemy — the enemy was right here at home.”

In Washington, D.C., 17-year-old Carrie Johnson opened fire on men breaking into her home while 1,000 white rioters laid siege to her neighborhood. In Anniston, Alabama, in December of 1918, a black veteran, Sergeant Edgar Caldwell, was ordered out of the white section of a streetcar. He refused. Kicked out of the car and set upon by the white motorman and conductor, Caldwell shot his pistol twice, killing one of his attackers.

Though uncoordinated, when looked at together, these hundreds of moments in and leading up to 1919 read as an awesome display of collective black agency and self-preservation.

Just as contemporary targets of anti-black violence are often blamed for their own victimization — Michael Brown was “no angel” while white supremacists in Charlottesville are deemed “very fine people” — the white media’s coverage of the 1919 riots almost always assigned blame for the violence to black people. But the black press, whose publishers and writers risked their lives in the pursuit of truth-telling, worked alongside black leaders and political organizations to establish a powerful counter-narrative. Black America’s most influential newspaper, the Chicago Defender, carefully documented the riots while striking a tone of defiance, saying, “A Race that has furnished hundreds of thousands of the best soldiers that the world has ever seen is no longer content to turn the left cheek when smitten upon the right.”

But students learn little of this early-20th-century episode of sustained, collective self-defense. Two of the three U.S. textbooks used in my school, outside of Portland, Oregon, devote only a single paragraph to the riots. The third has five paragraphs, focusing mostly on the D.C. riot, which would seem generous if the account didn’t distort the history and leave students mystified about racism’s role in the violence, writing:

Southern African Americans who had migrated to Washington, D.C., during the war had been competing for jobs in an atmosphere of mounting racial tension. Newspaper reports of rumored African American violence against whites contributed to the tension.

Following one such newspaper story, 200 sailors and marines marched into the city, beating African American men and women. A group of whites also tried to break through military barriers to attack African Americans in their homes. Determined to fight back, a group of African Americans boarded a streetcar and attacked the motorman and the conductors. African Americans also exchanged gunfire with whites who drove or walked through their neighborhoods.

By opening its analysis of the riots with black people migrating and seeking work, this textbook structurally implies it was the actions of African-Americans — rather than the white mobs — that prompted the violence. This is the same kind of backward reasoning that makes note of Trayvon Martin’s hoodie or Tamir Rice’s airsoft pellet gun in explaining their killings. In this framing, black people always “do” something which justifies the violence that follows; white violence and volition is always incidental, never fundamental.

The authors of the textbook also erase the magnitude and breadth of the self-defense effort. A black newspaper, the New York Age, celebrated as “splendid” the reach of the resistance, which included “poolroom hangers-on and men from the alleys and side streets, people from the most ordinary walks of life.” Neval Thomas, an active member of the Washington branch of the NAACP, counted 2,000 African-Americans — many of them armed — patrolling D.C. city blocks with the intention to “die for their race, and defy the white mob.” White people were not being targeted because they “walked or drove through” black neighborhoods, as the modern-day textbook suggests, but because thousands of white people had organized themselves into mobs, and black people were determined to protect themselves.

These textbooks peddle in the ambiguity of “racial unrest,” “racial violence,” and the most ubiquitous offender, “race riot,” to describe the events of 1919. These phrases give the impression of groups of blacks and whites in conflict with each other, responsibility shared by “both sides.” But there is little doubt about who instigated these riots. As Cameron McWhirter has written, “In almost every case, white mobs — whether sailors on leave, immigrant slaughterhouse workers, or southern farmers — initiated the violence.”

To capture the irrefutable fact of white culpability, a more accurate term might be racist riot. But “racism” or “racist” are terms these textbooks avoid.

The absence of a full-throated naming of racism’s role in these episodes of anti-black collective violence matters. By downplaying the extent to which violent white supremacy shaped African-Americans’ 20th-century experiences, textbooks leave students without the knowledge to fully account for racism as a key force in modern social relations. No wonder the question of reparations is so seldom seriously entertained in mainstream U.S. political discourse. We cannot repair a pattern of harm that we have been taught to neither acknowledge nor understand.

One hundred years ago, black people across the United States met white mob violence with countless defiant acts of self-defense. Today’s Black Lives Matter activists fit seamlessly into this centuries-long pattern of black militant resistance to white supremacy — as they mobilize against the violent policies and militarized police that threaten their neighborhoods, as they challenge corporate media’s habit of framing victims of white racist violence as the authors of their own destruction, as they demand we confront the damage white supremacy has wrought. Our students deserve the opportunity to identify this through line of black agency, rebellion, and resistance. It is a powerful call to action for all of us: Red Summer is now.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca is an organizer/curriculum writer for the Zinn Education Project and high school social studies teacher.

Spread the word