Over the last three years, Kenny Stills has not stuck to sports.

Instead, the Miami Dolphins receiver has kneeled during the national anthem before games to protest racial injustice. Taken an off-season road tripthrough the American south to visit community activists and civil rights movement landmarks. Publicly called out his own boss, Dolphins owner Stephen Ross, for the seeming incongruity of founding a nonprofit dedicated to racial equality – while also hosting a recent reelection fundraiser for US president Donald Trump.

The timeframe of his activism, Stills said, is hardly coincidental.

“Colin Kaepernick has played a really big part in helping open my eyes,” Stills said. “He’s influenced me and everything I’ve done from the time I first took a knee on September 11, 2016, to now.”

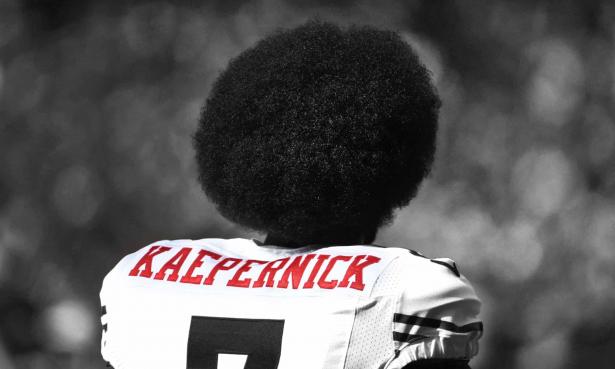

Last week marked three years since Kaepernick first brought attention to police brutality against people of color by sitting during the national anthem, a protest that ultimately led to the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback’s athletic exile.

Since then, Kaepernick has been awarded Amnesty International’s top honor. He has drawn Trump’s ire. He has inspired athletes like Stills, and been labeled a “traitor” by a NFL executive. He has served as the face of a multimillion-dollar Nike marketing campaign, and donated $1m to community charities. He has accused league owners of colluding to keep him out of football, and kept himself ready to play again.

A persona non grata in his sport, Kaepernick stands as a symbol of conscience outside of it. Yet for the most part, the quarterback has maintained radio silence, choosing to communicate with the media and public by sharing other people’s words on Twitter.

As such, it’s difficult to know exactly how Kaepernick views his time in the NFL wilderness. Nevertheless, it’s worth asking: after three years, what has he accomplished – and at what cost?

“Colin is a pioneer,” said Andrew Brandt, a former NFL front office executive who now writes about the league and is a sports law professor at Villanova University. “He is a beacon for other athletes. We can all talk about his impact. But he’s also not getting to do what he wants, which is play football. He has been ostracized.”

For now, at least, the answers depend on where you look.

The outcast

When Kaepernick first began protesting during the 2016 NFL preseason, he understood his actions would be controversial – and that he was taking a career risk.

“I am not looking for approval,” he said at the time. “If they take football away, my endorsements from me, I know that I stood up for what is right.”

Before Kaepernick sat, athletes ranging from WNBA players to the five members of the Los Angeles Rams to the NBA’s LeBron James, Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul, and Dwayne Wade had taken public stances against the racial injustice and police violence that spurred the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement and protests in places such as Ferguson, Missouri.

However, Kaepernick’s actions received far more attention, transforming him into a cultural and political flashpoint. His attempt to highlight what he called the “oppress of black people and people of color” quickly was lost amid heated debates about patriotism, sufficiently appreciating America’s military, and the appropriateness of mixing sports and politics.

After meeting with former NFL player and US Army veteran Nate Boyer, Kaepernick switched from sitting during the anthem to kneeling, the better to “show more respect for the men and women who fight for the country.”

Nevertheless, then-Republican presidential nominee Trump said that Kaepernick should “find a country that works better for him”. Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg labeled the quarterback’s actions “dumb and disrespectful”.

Meanwhile, conservative talk radio host Rush Limbaugh echoed a critique made by some football fans, lamenting that Kaepernick’s protests reflected the “politicization of everything”.

Within the NFL, reaction to Kaepernick was mixed – and largely split along racial and labor-management lines.

Then-49ers safety Eric Reid and other teammates joined the quarterback’s protests. Over the course of the season, African-American players for other teams followed suit, including Malcom Jenkins, Arian Foster, and Stills.

By contrast, seven anonymous league executives told journalist Mike Freeman that they wouldn’t sign Kaepernick to their teams. One called the quarterback a “traitor”. Another stated, “he has no respect for our country. Fuck that guy.”

“In my career,” a NFL general manger told Freeman, “I have never seen a guy so hated by front office guys as Kaepernick.”

Kaepernick entered free agency in the 2017 offseason as an accomplished performer at a position of perpetual league need. Over six seasons, the quarterback had thrown for 12,271 yards and 72 touchdown passes with just 30 interceptions; rushed for 2,300 yards and 13 touchdowns; and led the 49ers to a Super Bowl appearance.

He also had appeared on the cover of the popular Madden NFL video game.

Despite that resume, Kaepernick went unsigned by the NFL’s 32 teams. In June 2017, league commissioner Roger Goodell suggested that his absence was purely the result of “football decisions”.

As NFL teams subsequently hired a series of less-accomplished signal callers – including Zac Dysert, Josh Woodrum, and the immortal Matt Simms – Goodell’s assertion appeared increasingly dubious. In October 2017, Kaepernick filed a grievance against the league, accusing team owners of colluding to keep him from being signed because of his “advocacy for equality and social justice”.

Last February, Kaepernick and the NFL reached a confidential settlement of the case reportedly worth less than $10m. A few weeks earlier, an anonymous survey of 85 NFL defensive players by the Athletic found that 81 believed he deserved a roster spot in the league.

Today, however, Kaepernick remains a quarterback without a team – a former Pro Bowl performer whose most recent touchdown pass to a NFL player came in a March charity game.

“You’ve had people who have gotten DUIs coming back to the league,” said Lou Moore, a history professor at Grand Valley State University and author of We Will Win the Day: The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality. “Michael Vick came back to the league after dogfighting.

“The way the NFL works is, if you are good and can help a team, we will bring you in. Kaepernick is clearly good enough. And he didn’t come back. That says a lot about what the teams think about him. And the fact that he had to know that could cost him his career – and he still did it – says a lot about him.”

The beacon

Before Kaepernick’s first protest, Stills said, he wasn’t particularly interested in politics. He had never voted. He paid more attention to video games than to news. He didn’t know a lot about American history.

“It isn’t something we talked about much in my household,” he said.

Kaepernick sparked a change. Stills decided to vote in the 2016 election. He began keeping up with current events. He had long discussions with Foster, then his teammate on the Dolphins, who encouraged Stills to read and educate himself.

Stills started with The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, a critique of systemic racial discrimination in the justice system, then moved on to the works of African-American literary giant James Baldwin and civil rights leader John Lewis.

Stills shared what he was learning with family and friends. He organized his community service road trip. He began protesting during the anthem and also working with South Florida police, children, and community groups.

“ showed me that as athletes, there is something we can do,” Stills said. “We can use our platform to inform other people what needs to change. To help people who don’t have a voice be heard.

“People definitely ask me to stick to sports, and I totally understand where they are coming from. You want to be entertained, and get away from all the things that are happening. But that is also coming from a place of privilege.

“How do you think people feel who have lost kids to police brutality? Don’t you think they want to live their lives and be entertained like something never happened to them? I still catch passes and touchdowns and the games still go on – but these things are happening to human beings. It shouldn’t be hard to have a little bit of empathy.”

Stills isn’t alone. Soccer star Megan Rapinoe took a knee during the anthem in 2016 – and since has been anything but shy in expressing her disapprovalof Trump. College and high school athletes have staged anthem protests.

So have American hammer thrower Gwen Berry and fencer Race Imboden, who this month protested social injustice and Trump by raising a fist and taking a knee, respectively, on the medals stand at the Pan American Games.

The Players Coalition, a group of NFL players, leveraged anthem protests into a $89m social justice partnership with the league.

Moore said that Kaepernick has helped revive and galvanize a tradition of athlete activism that peaked in the 1960s when Muhammad Ali refused to fight in the Vietnam War and American track athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith gave black power salutes on the podium at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

That tradition largely went dormant in the 1980s and 1990s – in part because Ali, Carlos and Smith lost work and endorsement opportunities for their actions, and in part because many athletes followed the smiling, stick-to-sports examples of superstar pitchmen OJ Simpson and Michael Jordan, who embodied an anodyne ethos reflected in Jordan’s (possibly apocryphal) proclamation that “Republicans buy sneakers, too”.

Times change. Last September, the sports apparel company long associated with Jordan – Nike – featured Kaepernick in an advertising campaign with the slogan, “Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything”.

“Kaepernick’s actions and then the treatment he received are really the exclamation point on this new era of athlete activism,” said Kenneth Shropshire, CEO of the Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University and author of The Miseducation of the Student Athlete: How to Fix College Sports.

“A lot of people have tried to pinpoint where it began,” Shropshire said. “Was it the Rams? Was it LeBron in Miami with Trayvon Martin? What has become clear is that after folks saw Kaepernick, something different was going on.”

Waiting game

Earlier this month, Kaepernick posted a workout video on Twitter. Referring to his ongoing exile and desire to play, the post’s caption read “5am. 5 days a week. For 3 years. Still Ready.”

Brandt said that it’s unlikely that the 31-year-old free agent will get another NFL opportunity – at least not on the field.

“It’s not a question of talent,” Brandt said. “There are over 100 quarterbacks on rosters right now. And no one disputes that he is a top 100 quarterback. I think for teams, it just becomes: ‘Is he worth the drama?’

“But time heals all wounds. Maybe in five years, the NFL hires him for social activism. I think at some point there will be some kind of detente that does not involve him playing.”

Ali, Smith and Carlos were once reviled and shunned. Today, all three are widely admired – both for taking conscientious stands and enduring the price of doing so. Ali lit the Olympic flame at the 1996 Atlanta Games, while Smith and Carlos have been honored with a fist-raising statue at San Jose State University, their alma mater.

Moore said that Kaepernick will someday enjoy similar public regard.

“When you actually risk your livelihood in sports to stand up for social justice, the comparison is always to Ali, Smith, and Carlos,” Moore said. “But in the future, the question will be, ‘how does this compare to ?’ I think that is his legacy. In the end, people will embrace him. He will be loved.”

For now, Kaepernick continues to work, donating money to community charities and staging his Know Your Rights camps for young people. He also continues to wait. Last week, the NFL announced that Jay Z – who previously had expressed public support for the quarterback – would co-produce upcoming Super Bowl halftime shows and help promote the league’s social justice projects.

At a press conference, however, the headlining music mogul repeatedly was asked about one man. “Everyone’s saying, ‘How are you going forward if Kaep doesn’t have a job?’” Jay Z said. “This was not about him having a job.” That much rang false, and in a larger sense true, a reminder of everything Kaepernick has lost and won.

Spread the word