‘Anti-Alien Hysteria:’ Journalist Elizabeth Glendower Evans and the Trial of Sacco and Vanzetti

It was 1920, a time of heightened fear in the United States about immigrants and radicals. Two working men, Italian immigrants who spoke little English, were arrested in connection with a robbery and murder in South Braintree, Massachusetts. But Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti’s real crime was that they were anarchists and activists.

Both men had been actively organizing and raising funds for the defense of another Italian-born anarchist, Andrea Salsedo. Salsedo died two days before Sacco and Vanzetti’s arrest in an unexplained fall from the fourteenth story window of the Justice Department’s offices in New York City

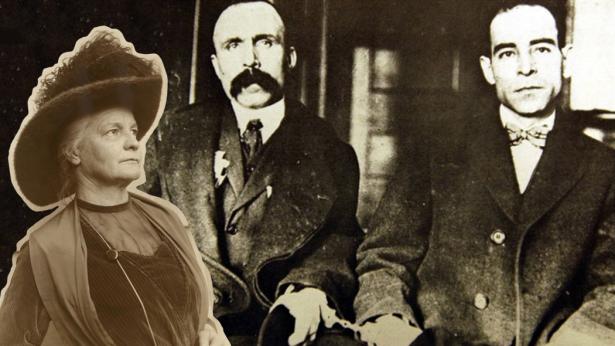

The trial of Sacco and Vanzetti became a rallying point for progressives, labor activists, and human rights advocates around the globe. Writing in La Follette’s Magazine, the former name of The Progressive, Elizabeth Glendower Evans, a Massachusetts-based civil liberties activist, covered the trial and its aftermath extensively between 1921 and 1928, bringing the case to the awareness of readers across the country.

Evans, attended the trial, visited the men in jail, and became acquainted with their families. As editor Belle Case La Follette later wrote in 1927, “In the beginning there was nothing personal in Mrs. Evans’ championship of the cause of Sacco and Vanzetti. She was not in sympathy with their revolutionary ideas nor with their opposition to the war and evasion of the draft. It was her sense of justice, her loyalty to the traditions of our free institutions, that first drew her into the fight.”

Evans first discussed the case in May 1921 with a column headlined: “Are We As Citizens on Guard? Amazing Story to be Revealed in Italian Trial in Massachusetts This Month; Human Rights Said to be the Issue.” Evans interviewed the two men in jail, and began to delve into the background of the case.

“My interviews with the accused so quickened my interest that I determined to read this record [of the evidence submitted] for myself. A more astonishing document never met my eyes,” she wrote. “No evidence is given showing why either Sacco or Vanzetti should have been held for the Braintree crime.”

Evans became convinced that the men were being scapegoated because they were immigrants and labor activists. She explained that “all this took place in the months when the anti-alien hysteria which had been gathering head since the war, came to a climax.” Reminiscent of today’s ICE raids and migrant detention camps, this era of anti-immigrant fervor included “red raids.” Evans wrote that in January 1920 about 5,000 foreign-born people were “rounded up and herded in police stations and jails, almost all of whom were found later to be innocent of any crime whatsoever, except that of having radical opinions . . . .”

Evans continued her coverage with an August 1921 column recounting the trial. “Every resource of the Government was strained to convict,” she wrote. “And in spite of the weakness of its case, it got what it wanted.” She detailed the ways in which the jury’s view was prejudiced by the prosecutor and the judge himself. “As draft evaders, they were objects of opprobrium, and the judge made strong appeal to the patriotic motive,” she observed.

By August 1925, there was a strong international movement in support of the men, including Harvard law professor and later Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, George Bernard Shaw, Albert Einstein, and H.G. Wells, among others. There was also ongoing pressure for a new trial in the now more than five-year-old case.

Evans returned to the pages of La Follette’s with a column titled, “When the Downtrodden Ask Justice.” Evans noted that the two men were arrested during a time of “anti-alien hysteria” and convicted of a crime they likely didn’t commit.

In January 1926, the Massachusetts Supreme Court heard an appeal of the case. A retrial was denied in spite of the fact that, as Evans reported, “Capt. Charles H. Proctor of the State Police, called as a government witness, had admitted, after the trial, that his testimony relative to the government’s claim that the mortal bullet had been fired from Sacco’s gun, had been purposely framed.”

In 1927, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled a second time that the case would not be retried, and in its written opinion took the odd legal tack of declaring: “It is not imperative that a new trial be granted, even though the evidence is newly discovered, and, if presented to a jury, would justify a different verdict.”

An execution date was set, prompting Evans to ask, in a May 1927 column, “shall Massachusetts commit judicial murder?” She described the scene from the month before, when Sacco and Vanzetti had appeared in court to receive this sentence: “Each of the men spoke . . . in simple, burning words, declaring their innocence of the crime of which they stood accused.”

Evans included a quote from Harvard professor William Ernest Hocking, who had spoken at a local church following that court appearance, stating, “The real enemies of the state are those who defend the indefensible, who refuse to acknowledge the error obvious to all thoughtful men, and who reject that primary concern for justice without which no law is worthy of respect and no state worthy of obedience.”

Afterward, Evans continued to correspond with the two men, using her June and July 1927 columns to share excerpts of letters she had received from them. (Nicola Sacco’s most famous letter, one written to his son Dante the night before his execution, was set to music by Pete Seeger.)

Sacco and Vanzetti both were executed in the electric chair on August 23, 1927. Evans’ column in September 1927 reported: “They laid their bodies in a little undertaker’s place in the North End of Boston where the Italians live in great number, and for three days and late into the night an endless file passed between the coffins and the wall, the space so narrow that time was allowed for scarce more than a glance. There were mounds of flowers upon the coffins and in the corners of the room, and masses of them outside in an entrance room.”

She also quoted Vanzetti’s remarks to the judge who had sentenced him to death: “If it had not been for these things, I might have live out my life, talking at street corners to scorning men. 1 might have die , unmarked, unknown, a failure. Now we are not a failure. This is our career and our triumph. Never in our full life can we hope to do such work for tolerance, for justice, for man’s understanding of man, as now we do by an accident.”

Fifty years after their deaths, in 1977, Sacco and Vanzetti were exonerated by Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, who said in a proclamation that their trial and execution “should serve to remind all civilized people of the constant need to guard against our susceptibility to prejudice, our intolerance of unorthodox ideas, and our failure to defend the rights of persons who are looked upon as strangers in our midst.”

Elizabeth Glendower Evans continued to work for justice and human rights until her death in December 1937. In December 1928, she wrote her last column on the Sacco and Vanzetti case for La Follette’s, chronicling new investigations into the case being taken up by other reporters.

Norman Stockwell is publisher of The Progressive.

Spread the word