Nearly a quarter of a million science teachers are hard at work in public schools in the United States, helping to ensure that today’s students are equipped with the theoretical knowledge and the practical knowhow they will need to flourish in tomorrow’s world. Ideally, they are doing so with the support of the lawmakers in their state’s legislatures. But in 2019 a handful of legislators scattered across the country introduced more than a dozen bills that threaten the integrity of science education.

It was a mixed batch, to be sure. In Indiana, Montana and South Carolina, the bills sought to require the misrepresentation of supposedly controversial topics in the science classroom, while in North Dakota, Oklahoma and South Dakota, their counterparts were content simply to allow it. Meanwhile, bills in Connecticut, Florida and Iowa aimed beyond the classroom, targeting supposedly controversial topics in the state science standards and (in the case of Florida) instructional materials.

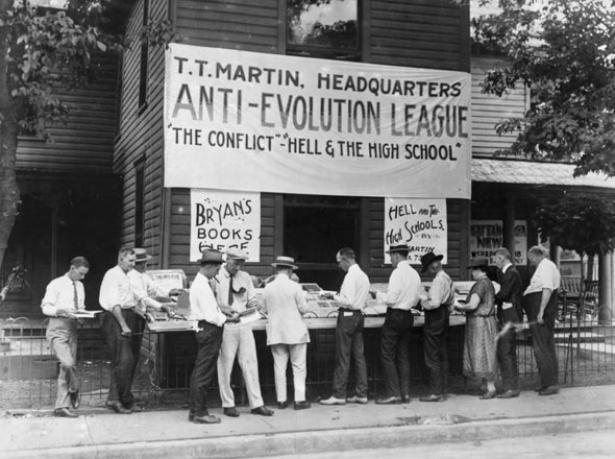

Despite their variance, the bills shared a common goal: undermining the teaching of evolution or climate change. Sometimes it is clear: the one in Indiana would have allowed local school districts to require the teaching of a supposed alternative to evolution, while the Montana bill would have required the state’s public schools to present climate change denial. Sometimes it is cloaked in vague high-sounding language about objectivity and balance, requiring a careful analysis of the motives of the sponsors and supporters.

Either way, though, such bills would frustrate the purpose of public science education. Students deserve to learn about scientific topics in accordance with the understanding of the scientific community. With the level of acceptance of evolution among biomedical scientists at 99 percent, and the level of acceptance of climate change among climate scientists not far behind at 97 percent, it is a disservice to students to misrepresent these theoretically and practically important topics as scientifically controversial.

The National Science Teaching Association agrees. In its position statement on the teaching of evolution, the NSTA describes evolution as “a major unifying concept in science” that “should be emphasized in K–12 science education frameworks and curricula.” Similarly, in its position statement on the teaching of climate science, the NSTA recommends that teachers of science “emphasize to students that no scientific controversy exists regarding the basic facts of climate change.”

Why, then, do legislators who should be trying to support science teachers introduce bills reflecting their own half-baked notions about science? Presumably in the service of gratifying ideologies—usually religious in the case of evolution; usually political in the case of climate change—to which they, and their constituencies, subscribe. That also helps to answer the question of why they introduce such bills even when the bills are—as in Connecticut, Indiana, Iowa, Montana and South Carolina—unlikely to be enacted.

But complacency about bills such as those in the current baker’s dozen ((?)) is unwarranted. Sometimes, after all, they succeed in passing. Louisiana and Tennessee passed laws in the last decade similar to the bills introduced this year in North Dakota, Oklahoma, and South Dakota, for example, and Florida recently passed a law enabling ideologically motivated challenges to instructional materials, which two of the three bills introduced there this year sought to expand further.

Moreover, the introduction of even the most hopeless of bills in a state legislature sends a message to teachers: that teaching evolution and climate change is unwelcome. Common sense suggests, and survey research confirms, that public school teachers are leery of teaching topics that they believe are regarded as controversial in their communities. Merely by taking a public stand against evolution and climate change, legislators may discourage educators from teaching these topics properly.

If public school science educators are not able to teach evolution and climate change honestly, accurately and confidently, then the scientific literacy of millions of students in America’s public schools is going to be in jeopardy. The lawmakers of the 50 state legislatures are responsible for supporting these teachers properly. It is up to us, their constituents, to ensure that they do—and to reproach them when they introduce their half-baked ideas to the contrary.

Glenn Branch is deputy director of the National Center for Science Education.

Spread the word