The White House is taking steps toward decisive new action on homelessness, bucking policies favored by advocates in favor of an aggressive approach that centers the role of law enforcement. Some of these efforts hit roadblocks this week, but more measures are in the works—including a rumored executive order on homeless encampments.

Advocates say that they expect an executive order on homelessness to assign new resources to police departments to remove homeless encampments and even strip housing funds from cities that choose to tolerate these encampments. It’s one of several efforts being steered by the White House’s Domestic Policy Council in concert with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

On Monday, Housing Secretary Ben Carson met with local officials in Houston, part of a push for federal action on homelessness that could soon take shape in cities across the country. The secretary visited an emergency shelter and was slated to tour a former Harris County jail facility, according to advocates familiar with his agenda. Officials at HUD have been looking at real estate in several cities since the fall, when President Donald Trump ordered a sweeping federal response to homelessness.

Carson’s latest stop is yet another signal that the administration is keen to take a hands-on approach to people who sleep on the street. Advocates say that the government is looking closely at ways to turn former correctional facilities and federal buildings into shelters, a controversial approach backed by Robert Marbut, the newly appointed White House czar on homelessness.

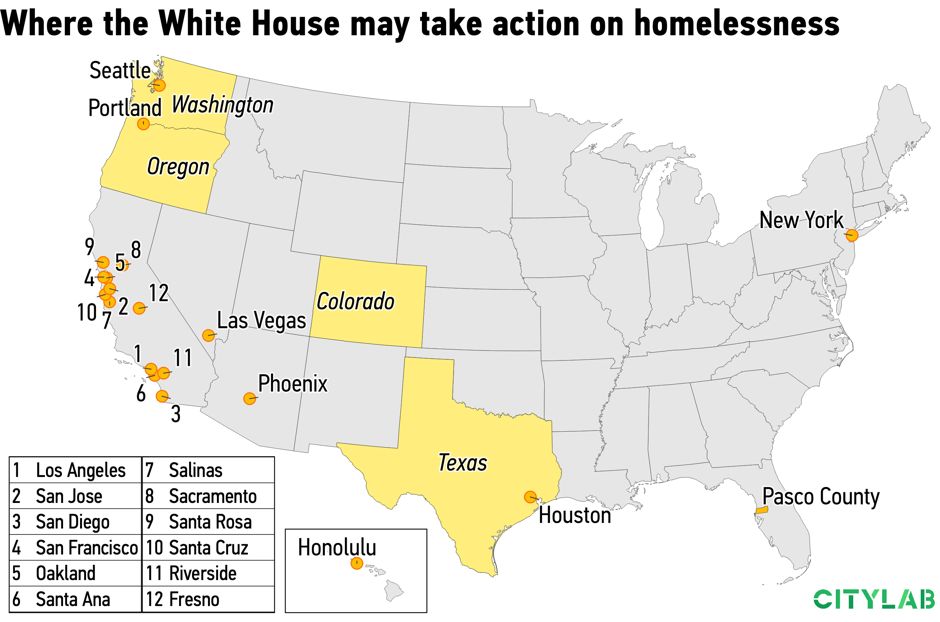

One advocate for a Washington, D.C.-based housing organization says that HUD has narrowed its focus to a list of 24 cities and states, all of which have large numbers of unhoused people sleeping outside. Most are located on the West Coast, where Trump has sought to embarrass progressive officials by intervening. Houston is among the cities on this list, obtained by CityLab, where local and regional bodies known as continuums of care (CoCs) face high unsheltered counts. In addition to 20 cities, four of the places named on the list are states that have homeless populations outside the largest urban centers.

While Houston made its way onto HUD’s potential action list, the city has made significant progress in recent years in curbing homelessness, especially relative to other cities in Texas. Over the last decade, the city has cut the number of people experiencing homelessness by more than half. And despite a recent increase following Hurricane Harvey, the trend is still stable or downward, unlike in Dallas, Austin, and other places.

Yet housing advocates fear that the White House favors a punitive approach for Houston, where—as in other Texas cities—homeless encampments are increasingly visible. “I hope that what takes away is that if you really turn all your resources to permanent housing and ending homelessness, instead of managing the condition of homelessness, it can have dramatic results,” says Eva Thibeaudeau, CEO of Temenos, a community development corporation that operates about 140 performance supporting housing units in Houston.

Since 2011, the city has marked a 54 percent decline in people experiencing homelessness, according to local point-in-time counts. Thibeaudeau credits the falling numbers of people living on the streets to the city’s adherence to a set of principles known as Housing First. The policy has enabled Houston to put more than 18,000 people into permanent housing situations with their own leases. “We shifted a lot of dollars out of short-term, temporary, high-barrier projects, and reallocated them all toward permanent solutions,” Thibeaudeau says. “That really is the reason that our homelessness has been driven down.”

Housing First runs contrary to the approach favored by Marbut, the consultant who was named director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness last week. Marbut has pushed for shelters that set up barriers to treatment, namely sobriety. For example, at Haven for Hope, a shelter founded by Marbut in San Antonio, homeless people with substance-abuse problems must sleep outside in an exposed courtyard until they can pass a drug test.

In Houston, Temenos manages so-called wet housing: The group works with city and county officials and sobering centers to identify people struggling with long-term alcoholism and addiction who are facing chronic homelessness and give them permanent support, including three meals per day and a lease.

In September, when the White House released a report on homelessness, it signaled a change away from the Housing First direction long favored by the Interagency Council on Homelessness. Going forward, the administration appears to be leaning on a prominent role for law enforcement, with a focus on shelters that sequester homeless people away from downtown in large, centralized facilities.

Late in November, an official at HUD sent an email to Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler and other officials in Oregon to express Carson’s interest in determining whether an unused jail in Portland could be repurposed for a pilot program to address homelessness, according to a report in Willamette Week. And in September, Carson and other officials at HUD visited a former federal office building just outside Los Angeles, a move that sparked fears among housing advocates that the Trump administration could be planning a crackdown on Skid Row’s unhoused population.

The Trump administration may pursue its agenda on homelessness on other fronts. An executive order—said to be the brainchild of Benjamin Hobbs, special assistant to the president for domestic policy—might not materialize for weeks (if ever). But such an executive action would reinforce the dynamic in Texas, where the conservative governor has sought to overrule the work of liberal leaders in Austin to legalize tent encampments, for example.

But the broader campaign to criminalize homelessness hit a snag on Monday, when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear a case from Boise, Idaho, about whether local and state governments can make it a crime for people to sleep outside. A Supreme Court decision that overturned the federal appeals court’s decision might have enabled cities to prosecute people forced to sleep outside.

“We’re thrilled that the court has let the 9th Circuit decision stand so that homeless people are not punished for sleeping on the streets when they have no other option," Maria Foscarinis, executive director of the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty, told USA Today.

In yet another front of the administration’s efforts, the White House also pushed hard to strip Housing First language from funding measures in the appropriations bill passed on Monday night, according to advocates. But the bill still retains language from 2018 that prioritizes funds for groups that adhere to Housing First goals.

There are still some legal impediments to banning encampments or stripping funds from groups that choose to put housing needs before behavioral modification. But those may not be enough to prevent the White House from implementing a strategy that local leaders describe as an about-face from what they’ve been pursuing for years.

“The Houston approach in general has not been to pour a lot of money into emergency-type facilities,” Thibeaudeau says. “We’ve chosen instead to use that money to increase our supply of permanent supportive housing.”

Kriston Capps is a staff writer for CityLab covering housing, architecture, and politics. He previously worked as a senior editor for Architect magazine.

Love CityLab? Make sure you're signed up for our free e-mail newsletter(s).

Spread the word