Introduction and key findings

From teachers in North Carolina to hospital workers in California, and from autoworkers in Michigan to grocery store cashiers in Boston, workers across the United States have participated in a resurgence in major work stoppages in the last two years. By far the most common form of work stoppage is a strike, which is when workers withhold their labor from their employer for a period of time during a labor dispute. By withholding their labor—labor that employers depend on to produce goods and provide services—workers are able to counteract the inherent power imbalance between themselves and their employer. In this way, strikes provide critical leverage to workers when bargaining with their employer over fair pay and working conditions or when their employer violates labor law.

In this brief, we cover the basics of strikes—who has the legal right to strike and when—and what policies to strengthen the right to strike are under consideration. We also analyze new data on major work stoppages from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) showing that after decades of a downward trend, there has been an upsurge in strike activity in the last two years.1

At first blush, it may seem odd that the United States is seeing a resurgence in strike activity when the unemployment rate is below 4%. The increased activity likely stems from two factors. First, workers know that if they are fired or otherwise pushed out of their jobs for participating in a strike (which is illegal but common behavior among employers), they are more likely to be able to find another job. Second—and perhaps even more important—working people are not seeing the robust wage growth that one might expect with such a low unemployment rate, and inequality continues to grow. The increase in strike activity suggests that working people are concluding that if even a sub-4% unemployment rate 10 years into an economic recovery is not providing enough leverage to generate truly robust wage growth, workers must join together to demand a fair share of the recovery.

Who has the legal right to strike?

Most private-sector workers in the United States are guaranteed the right to strike under Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). Section 7 of the Act grants workers the right “to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” This allows private-sector workers to engage in “concerted activities” such as strikes, regardless of whether the worker is in a union or covered by a collective bargaining contract. There is no federal law that gives public-sector workers the right to strike, but a dozen states grant public-sector workers the right to strike.2

In general, there are two types of strikes: economic strikes and unfair labor practice strikes. In an economic strike, workers withhold their labor as leverage when bargaining for better pay and working conditions. While workers in economics strikes retain their status as employees and cannot be discharged, their employer has the right to permanently replace them.3 At the conclusion of an economic strike, replaced workers are not automatically reinstated in their old jobs, but they have priority to apply for any future job openings. In other words, while workers have the legal right to participate in an economic strike—and remain employees while on strike—current law makes participation risky because workers might be out of a job when the strike concludes.

In an unfair labor practice strike, workers withhold their labor to protest their employer engaging in activities that they regard as a violation of labor law. Workers in an unfair labor practice strike cannot legally be discharged or permanently replaced. When an unfair labor practice strike concludes, workers who were on strike are entitled to be reinstated even if replacement workers have to be discharged. Workers in both economic and unfair labor practice strikes are entitled to back pay if the National Labor Relations Board finds that the employer unlawfully denied the workers request for reinstatement.

While Section 7 of the NLRA provides workers the right to strike, not all strikes are lawful. Under Section 8(b)(4) of the Act, it is currently unlawful for workers to be involved in “secondary” strikes, which are strikes aimed at an employer other than the primary employer (for example, when workers from one company strike in solidary with another company’s workers). If a strike is deemed an “intermittent strike”—when workers strike on-and-off over a period of time—it is not protected as a lawful strike by the NLRA. In general, a strike is also unlawful if the collective bargaining agreement between a union and the employer is in effect and has a “no-strike, no-lockout” clause.

Upsurge in very large work stoppages in the last two years

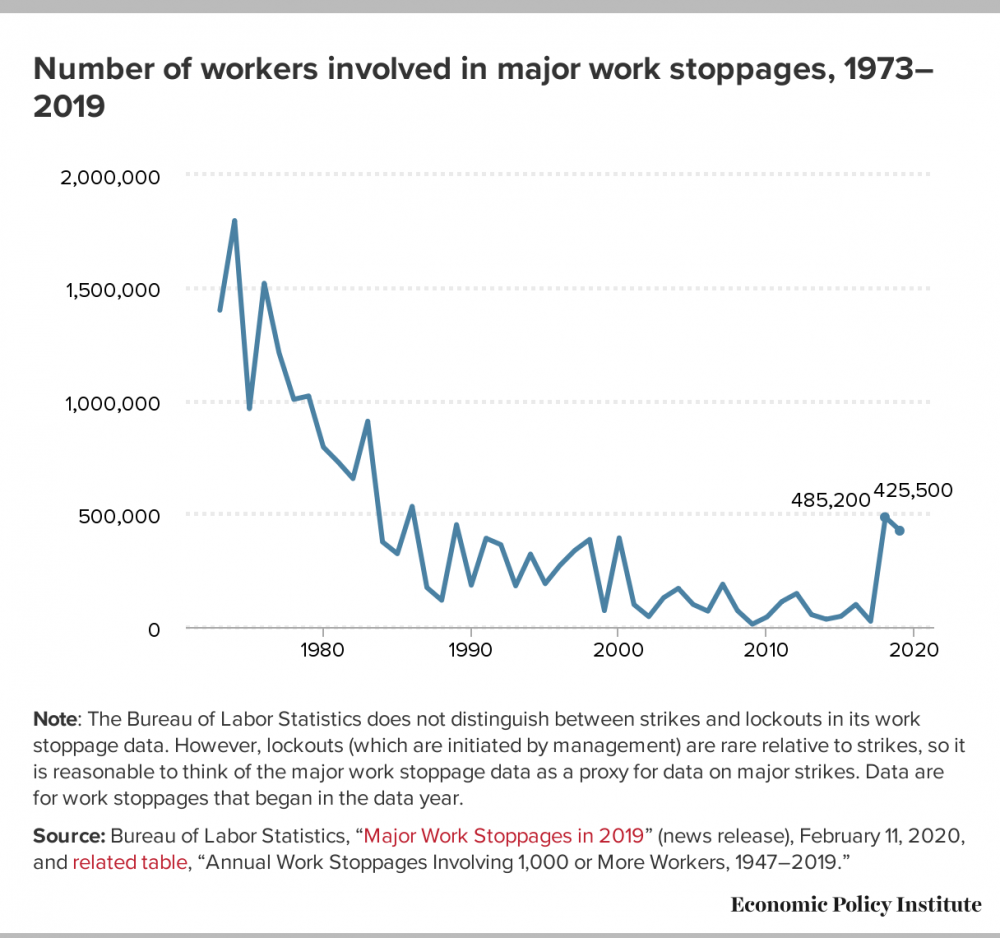

BLS data on major work stoppages–work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers lasting one shift or longer—show that 425,500 workers were involved in major work stoppages that began in 2019.4 The 2019 level was slightly lower than the 2018 level, but as Figure A shows, there has recently been a meaningful “break” in the series. Through 2017, the general trend was downward, but there was a substantial upsurge in workers involved in major work stoppages in 2018. On average, in 2018 and 2019, 455,400 workers annually were involved in major work stoppages—the largest two-year pooled annual average in 35 years, since 1983 and 1984.

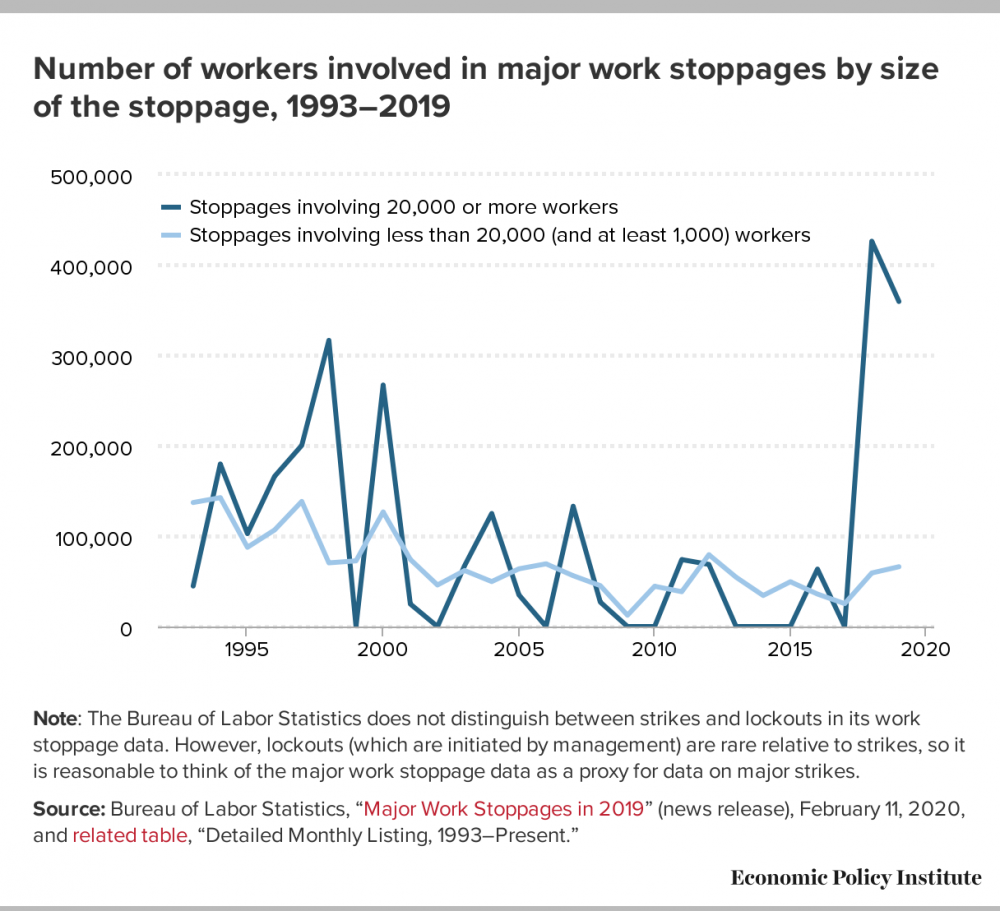

One thing that is important to note when comparing the number of workers involved in major work stoppages over time is that other things in the economy have evolved as well. For example, the number of union members has declined, from 21 million in 1979 to 14.6 million in 2019.5 This means the share of union members involved in a major work stoppage has declined somewhat less rapidly than the raw levels over this period (the surge in 2018 and 2019 notwithstanding).6 In the 2018 and 2019 period, 3.1% of union members were involved in a work stoppage each year on average—a level of sustained resistance not seen since 1983.7 Furthermore, in the last two years, major work stoppages have involved more workers than ever before. In 2018/2019, an average of 20,000 workers were involved in each major work stoppage—the highest two-year average on record, back to 1947. By contrast, in earlier years when there were many more major work stoppages, they tended to be smaller. For example, 1952 had 470 major work stoppages—the most on record and many times the 25 major work stoppages that occurred in 2019—but each major work stoppage in 1952 involved “just” 6,000 workers on average.8

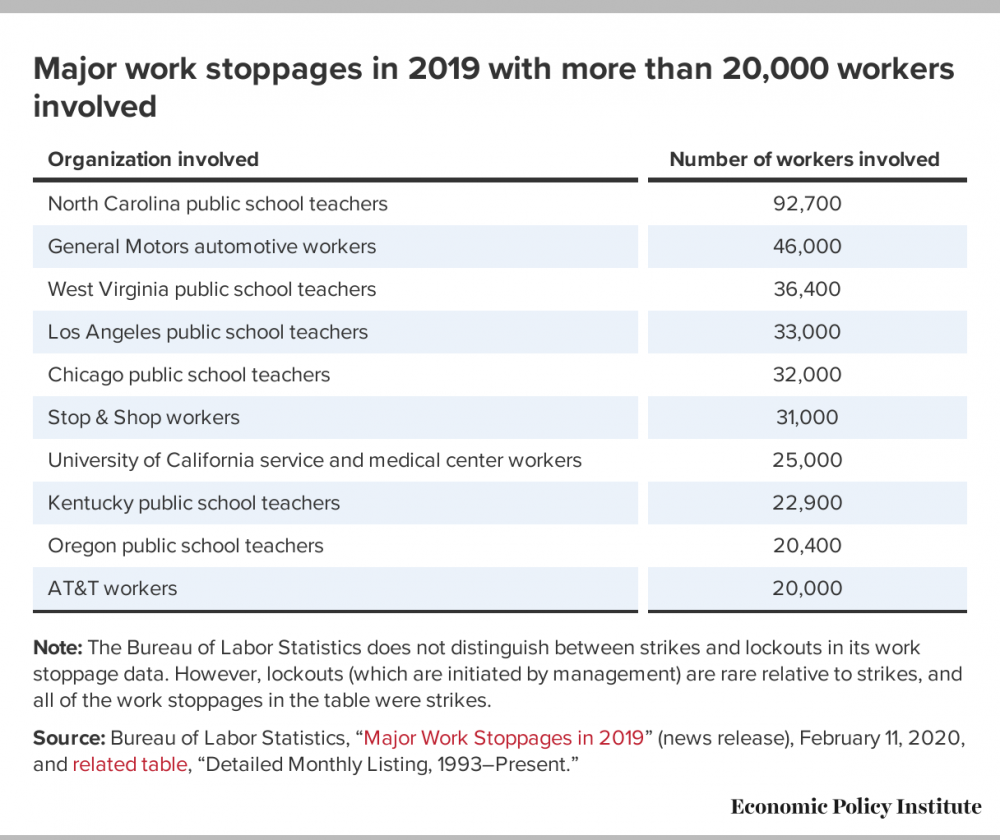

Figure B breaks down the data from Figure A into two sizes of major work stoppages—stoppages involving 20,000 workers or more, and stoppages involving at least 1,000 but less than 20,000 workers. The data to compute this breakdown are available only for 1993 and later years.9 The figure shows that the 2018 and 2019 upsurge in workers involved in major work stoppages has largely been the result of an increase in very large work stoppages—work stoppages involving at least 20,000 workers. In fact, in 2019, there were 10 work stoppages involving at least 20,000 workers, the largest number of work stoppages of this size since before 1993, when the data on work stoppages by size became available. Table 1 lists the 2019 work stoppages that involved more than 20,000 workers by organization name and number of workers involved.

Limitations of the BLS data on work stoppages

The BLS data on work stoppages, while useful, have a major limitation—the data include only information on work stoppages involving 1,000 or more workers that last at least one full shift. There is an enormous amount of information that is missed by restricting the data to work stoppages involving at least 1,000 workers, as evident in BLS data on firm size: according to the BLS, nearly three-fifths (59.4%) of private-sector workers are employed by firms with fewer than 1,000 employees.10 Restricting the tracking to actions that last at least one full shift also misses important work stoppages. For example, the data do not include the 2018 Google walkouts in protest of the company’s handling of sexual harassment, because even though the walkouts involved thousands of workers, they did not last for one full shift.11 Unfortunately, comprehensive data on work stoppages that involve fewer than 1,000 workers, or that last less than one full shift, are not readily available from BLS or other sources. Thus, there is a large gap in knowledge about the true extent of, and trends in, strike and lockout activity.

Examples of major work stoppages in 2018 and 2019

Teacher strikes

In February 2018, teachers went on a statewide strike in West Virginia to demand just wages and better teaching and learning conditions. For nine days, schools across the state were closed as teachers, students, and community supporters protested at the state capital against the state government’s chronic underfunding of public education and the impact on the teachers and students. After a week and a half on strike, the West Virginia teachers received a pay increase. They also sparked a movement that prompted public school teachers in other states to strike in support for better pay and working conditions.12

Consequently, the largest work stoppages by number of workers during 2018 and 2019 were in elementary and secondary schools in states such as Arizona, Colorado, Kentucky, North Carolina, and West Virginia.13 Community support, such as students and parents protesting in solidarity at schools and state capitals, made it possible for hundreds of thousands of teachers to strike in an effort to improve their pay and working conditions.

The General Motors strike

In the early hours of September 16, 2019, nearly 50,000 workers walked out of General Motors (GM) factories across the nation and went on strike. The action followed GM’s decision to close multiple U.S.-based factories and move jobs abroad, even after the company received millions in corporate tax cuts.14 GM workers went on strike to preserve job security, improve wages, and retain health care benefits. The GM strike was the longest major work stoppage in 2019, with over 1.3 million days idle.15 The strike was also the first GM strike in over a decade.

The six week strike concluded with the United Auto Workers and GM agreeing to a four-year contract that improved wages, sustained health care costs for workers at existing levels, created a transition process for temporary workers to become permanent employees, and committed to making investments in American factories.16 In addition to improving the pay and working conditions of GM workers, the final contract will serve as a template for UAW’s contracts with Ford and Chrysler, creating a set of standards in the automotive industry.17

The Stop & Shop strike

Another notable major work stoppages of 2019 was the Stop & Shop strike. More than 30,000 workers at the New England-based grocery chain went on strike after negotiations over new contracts stalled for three months. During those negotiations, Stop & Shop had offered workers across-the-board pay increases but also proposed increasing the cost of health care, ultimately negating the pay raises. The workers argued that Stop & Shop could offer better compensation than it did because the company reported profits of more than $2 billion in 2018.18 As a result of the impasse, workers in over 240 locations went on strike for better pay and benefits during the week of Easter.

The Stop & Shop strike was the second largest private industry work stoppage in 2019, with over 215,000 days idle. The 11 day strike concluded with the United Food and Commercial Workers and Stop & Shop agreeing to a three-year contract that preserved health care benefits, increased wages, and maintained time-and-a-half pay on Sunday for current employees.19

Policies to strengthen the right to strike

The resurgence is in strike activity is occurring despite current policy that makes it difficult for many workers to effectively engage in their fundamental right to strike.

The Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act includes critical reforms that would strengthen workers’ right to strike. The PRO Act would expand the scope for strikes by eliminating the prohibition on secondary strikes and by allowing the use of intermittent strikes. It would also strengthen workers’ ability to strike by prohibiting employers from permanently replacing striking workers. Further, the PRO Act would strengthen undocumented workers’ right to strike by overturning the Supreme Court’s decision in Hoffman Plastic Compounds v. NLRB, which held that undocumented workers are not entitled to reinstatement or back pay if their employer violated their workplace rights. The PRO Act passed the House of Representatives February 6, 2020, but is unlikely to advance in the Senate in the near future.

In addition to the crucial reforms found in the PRO Act, there are additional solutions under discussion that would strengthen the right to strike, including extending unemployment benefits to striking workers, creating tax-deductible strike funds to make it easier for unions to sustain long-term strikes, and forming digital picket lines to inform consumers of real-life collective actions during online interactions with the workers’ employer.20 All of these policies, and those of the PRO Act, are part of an important effort to bring U.S. labor law into the 21st century.

Conclusion

The unemployment rate averaged 3.8% in 2018 and 2019, its lowest level in 50 years. At first blush, it may seem odd that the U.S. is seeing a resurgence in strike activity at a time like this. The increased activity likely stems from two factors. First, workers know that if they are fired or otherwise pushed out of their job for participating in a strike (which is illegal but common), they are more likely to be able to find another job. Second and perhaps even more important, working people are not seeing the robust wage growth that one might expect with such a low unemployment rate, and wage levels for working people remain low, with many families struggling to make ends meet. The wage of the median worker is about $19 per hour, which translates to about $40,000 per year for a full-time, full-year worker, a level that suggests that the U.S. economy is not delivering for many working people.21 Further, inequality continues to rise, as the people who already have the most see strong gains.22 The increase in strike activity suggests that more and more, working people are concluding that if even a sub-4% unemployment rate 10 years into an economic recovery is not providing enough leverage to meaningfully boost their wages, they must join together to demand a fair share of this recovery.

About the authors

Heidi Shierholz is a senior economist and the director of policy at EPI. She previously served as chief economist at the U.S. Department of Labor. Margaret Poydock is policy associate at EPI. She previously held legislative positions in the U.S. Senate.

Endnotes

1. The BLS Work Stoppages program provides monthly and annual data on work stoppages (strikes and lockouts) involving 1,000 or more employees. Both strikes and lockouts are work stoppages initiated during a labor dispute for the purpose of gaining leverage, but whereas strikes are initiated by workers, lockouts are initiated by management. BLS does not distinguish between strikes and lockouts in its work stoppage data. However, lockouts are rare relative to strikes, so it is reasonable to think of the major work stoppage data as a proxy for data on major strikes.

2. Kirsten Bass, “Overview: How Different States Respond to Public Sector Labor Unrest,” On Labor, March 11, 2014.

3. In NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that employers can permanently replace striking workers in order to keep their business running during a work stoppage.

4. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Major Work Stoppages in 2019” (news release), February 11, 2020.

5. Union Stats, “Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment among All Wage and Salary Workers, 1973–2018” (web page), accessed on February 7, 2020.

6. Another thing that has evolved is the fact that employment of wage and salary workers has grown substantially, from 87.1 million in 1979 to 141.7 million in 2019. (See Union Stats, “Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment Among All Wage and Salary Workers, 1973–2018” (web page), accessed February 7, 2020.) This means the share of workers involved in a major work stoppage has declined more rapidly than the raw levels have declined over this period (again, the surge in the 2018 and 2019 period notwithstanding).

7. It is important to note that strikes and lockouts may involve workers who are not union members. However, because strikes and lockouts are far more likely to involve union members, it is reasonable to look at the number of workers involved in a work stoppage as a share of union members.

8. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Major Work Stoppages in 2019” (news release), February 11, 2020, and related table, “Annual Work Stoppages Involving 1,000 or More Workers, 1947–2019.”

9. Data with the aggregate number of major work stoppages and the aggregate number of workers involved in major work stoppages are available annually from 1947. But data showing the size of each major work stoppage (which allows for the determination of whether an individual work stoppage involved 20,000 workers or more), are only available from 1993.

10. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Table F. Distribution of private sector employment by firm size class: 1993/Q1 through 2019/Q1, not seasonally adjusted,” [web page], National Business Employment Dynamics Data by Firm Size Class, last modified January 29, 2020.

11. Taylor Telford and Elizabeth Dwoskin, “Google Employees Worldwide Walk Out Over Allegations of Sexual Harassment, Inequality Within Company,” The Washington Post, November 1, 2019.

12. Katie Reilly, “‘I Work 3 Jobs and Donate Blood Plasma to Pay the Bills.’ This is What It’s Like to Be a Teacher in America,” Time, September 13, 2020.

13. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Major Work Stoppages in 2019” (news release), February 11, 2020, and related table, “Detailed Monthly Listing, 1993-Present.”

14. Americans for Tax Fairness, “GM Layoffs Prove Tax Cuts Hurt, Don’t Help, Workers,” Americans for Tax Fairness, November 27, 2019.

15. Days idle refers to the number of working days lost multiplied by the number of workers.

16. Alexia Fernández Campbell, “The GM Strike Has Officially Ended. Here’s What Workers Won and Lost.,” Vox, October 25, 2019.

17. Alexia Fernández Campbell, “GM Workers Are on Strike to Accomplish What Trump Couldn’t,” Vox, September 17, 2019.

18. Sarah Betancourt, “Stop & Shop Hit by Strike As 31,000 Workers Walk Off Job,” Guardian, April 19, 2019.

19. Sandra E. Garcia, “Stop & Shop Strike Ends With Union Claiming Victory on Pay and Health Care,” New York Times, April 22, 2019.

20. Sharon Block and Ben Sachs, Clean Slate for Worker Power: Building A Just Economy and Democracy, Clean Slate for Work Power, January 2020.

21. Elise Gould, “On the other hand, the 20th percentile has done better over the last two years, and in fact exhibited the strongest growth (+2.6 percent annualized) over the last two years compared to any other decile, including the 95th percentile. 21/n,” Twitter, @eliselgould, August 2, 2019, 10:19 a.m.

22. Lawrence Mishel and Melat Kassa, “Top 1.0% of Earners See Wages Up 157.8% Since 1979,” Working Economics (Economic Policy Institute blog), December 18, 2019.

Spread the word