Frida Kahlo made a dramatic entrance to her only solo show in Mexico City. The artist arrived by ambulance and had to be stretchered into the gallery. Her sick bed, which had preceded her by truck, awaited her. The tequila flowed.

The 46-year-old artist, who had less than a year to live, spent many months confined to bed by injury and illness during her short life. But her bedroom in La Casa Azul, the family home in Mexico City that she transformed into a sanctuary and menagerie, was where she blossomed as an artist.

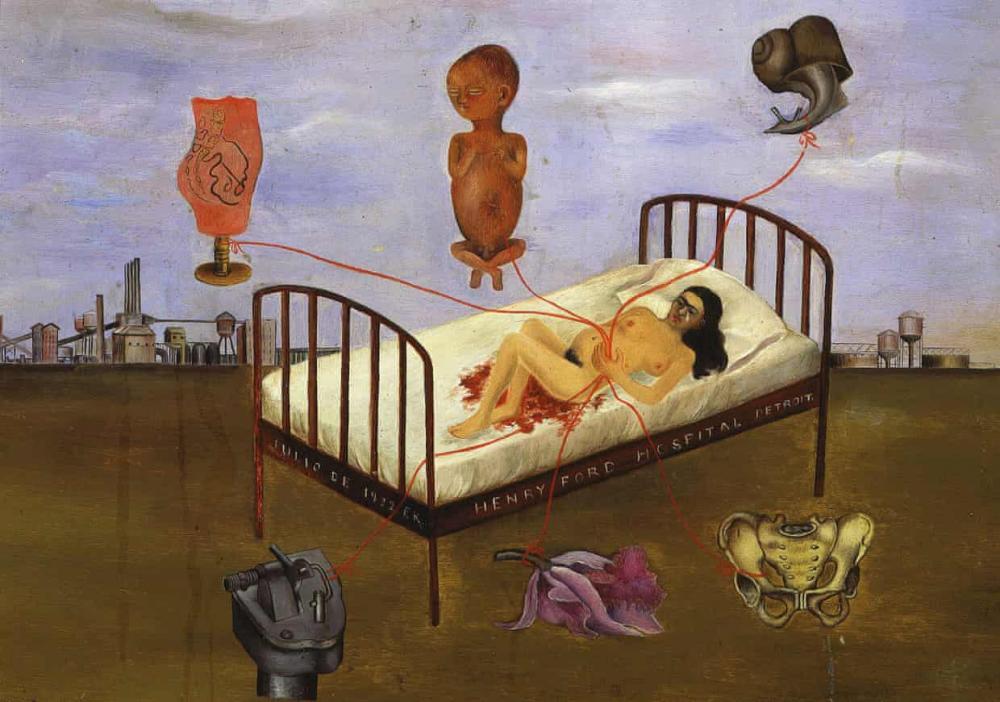

Photograph: c 2020 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York // The Guardian

“She made art out of her pain and her frustration,” says the author Jessie Burton, who painted her own writer’s hut blue as a homage to the Mexican artist’s home in Coyoacán. “Being contained not just in her house but in a bed for so long meant her art was almost like a metaphysical resistance. She was going to break out of those four walls, express herself and tell her story through painting.”

Kahlo’s life story, a triumph of creativity against the odds, makes her a role model for an artist in quarantine. Most of her paintings are modest in size but pack a powerful punch. While Diego Rivera, her older and more famous husband was painting murals in Detroit in the 1930s, she was painting an early masterwork, the nude-self portrait Henry Ford Hospital, to channel the grief and trauma of losing a child, coupled with the death of her mother. It is the first depiction of a miscarriage in western art history.

Back in Mexico, her bedroom was a safe haven but it was also a stage. Burton says that there is always an element of performance in her art and the way she fashioned her image. “All of these paintings are gestures of keeping up one’s spirit, accepting one’s lots and doing the best with it but there were a lot of complicated things going on.”

Kahlo might seem the modern artist most suited to self-isolation but she would have hated not being able to socialise and flirt. One of several lovers, the artist Isamu Noguchi, had to flee the Casa Azul when almost caught in bed with Kahlo by a gun-toting Rivera. Noguchi recalled: “Everything that she couldn’t do, she loved to do. It made her absolutely furious to be unable to do things.” That included dancing, despite her disabilities.

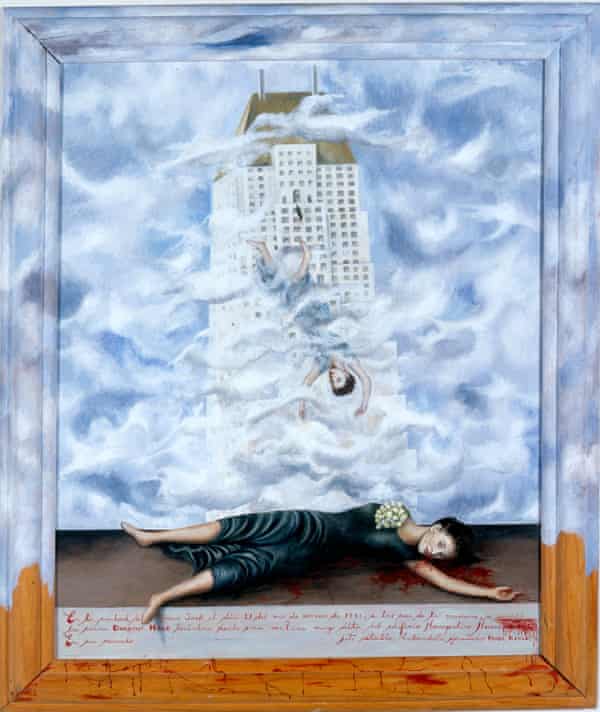

Photograph: Gianni Dagli Orti/Rex/Shutterstock // The Guardian

In the year she spent bed-bound afterthe crash, Kahlo abandoned her plan to become a doctor and turned to art. The artist’s familiarity with death, which she nicknamed “la pelona,” the bald one, meant she never pulled her punches on canvas. She had no hesitation about portraying blood, her own and other’s. The American playwright and politician Clare Boothe Luce was shocked to receive a portrait she commissioned from Kahlo of a mutual friend. The Suicide of Dorothy Hale depicts the death of the aspiring actor, who jumped off a skyscraper. It is one of Kahlo’s most surrealist works, a label she rejected. “I never painted my dreams,” she said. “I painted my reality.”

Kahlo’s art also continues to resonate today because of her radical politics. An idiosyncratic mix of communism, Mexican pride and lapsed Catholicism, she was a far more outspoken critic of America than her husband. Henestrosa points to a late, unfinished self-portrait of 1954 in which Stalin looms over Kahlo. It is not the kind of image reproduced in Kahlo kitsch and merchandise. Her Marxism recently irked Donald Trump’s US ambassador Christopher Landau, who tweeted on a visit to Casa Azul that he admired the artist but had problems with her admiration of Stalin.

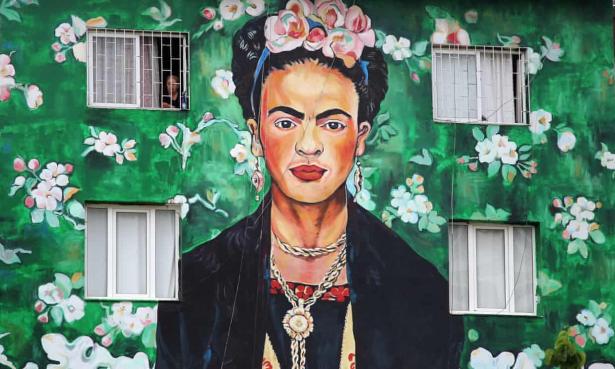

Photograph: Craig Smith/Collection of Phoenix Art Museum, gift of an anonymous donor // The Guardian

Henestrosa had just finished installing an exhibition of the artist’s extraordinary wardrobe in San Francisco’s de Young Museum when coronavirus hit. The clothes and paintings now hang in darkened galleries. The museum’s director, Thomas Campbell, who hopes to extend the loans so the show can reopen, says that Kahlo’s words - “Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly?” - have become an inspirational mantra during the lockdown.

Hettie Judah has written a new book about Kahlo, which is due to be published later this year. She describes how, when ill and near death, Kahlo recalled in her diary an earlier period of confinement. As a child, struck down with polio, she would breathe against the window of her bedroom and draw a door through which she escaped in her imagination.

Like the elderly Matisse, painting and collaging in the south of France, Kahlo transformed her mundane surroundings into something magical. But unlike the French artist, there was nothing soothing about her art.

[Essayist Javier Pes is a London-based journalist and a regular contributor to Artnet.com. His work can be found HERE ]

Spread the word