In 1969, the Children’s Television Workshop made a twenty-six-minute pitch reel to line up stations to air a radically new program that appeared to have, as yet, no title. Instead, a team of fleece- and fur- and muddle-headed puppets were seen brainstorming in a boardroom.

“What are those guys doing?” a dubious green frog asks, peering into the room with Ping-Pong eyes.

“Well, you see, we haven’t settled on a title for the show yet, so the guys are working on it,” a floppy-eared dog with a wide mouth says.

The guys come up with some whoppers. Like “The Two and Two Are Five Show.”

“Two plus two don’t make five, you meatball!”

“They don’t? Then how about ‘The Two and Two Ain’t Five Show’?”

Then they try out a title that keeps getting longer and longer.

“Howzabout we call it ‘The Little Kiddie Show’?”

“But we oughta say something about the show telling it like it is! Maybe ‘The Nitty Gritty Little Kiddie Show’?”

The frog, named Kermit, shakes his head at his dog friend, Rowlf. “Are you really gonna depend on that bunch to come up with a title?”

“You never can tell, Kermit,” Rowlf says, with a hopefulness known only to dogs. “They just might think of the right one.”

Half a century ago, before “Sesame Street,” and long before the age of quarantine, kids under the age of six spent a crazy amount of time indoors, watching television, a bleary-eyed average of fifty-four hours a week. In 1965, the year the Johnson Administration founded Head Start, Lloyd Morrisett, a vice-president of the Carnegie Corporation with a Ph.D. in experimental psychology from Yale, got up one Sunday morning, at about six-thirty, a half hour before the networks began their day’s programming, to find his three-year-old daughter, Sarah, lying on the living-room floor in her pink footie pajamas, watching the test pattern. She’d have watched anything, even “The Itty-Bitty, Farm and City, Witty-Ditty, Nitty-Gritty, Dog and Kitty, Pretty Little Kiddie Show.”

Not much later, Morrisett fell into a dinner-party conversation with Joan Ganz Cooney, a public-affairs producer at New York’s Channel 13. The first time Cooney had seen a television set was in 1952, when she watched Adlai Stevenson accept the Democratic nomination. She’d gone on to champion Democratic causes and had moved from Phoenix to New York to work at Channel 13, where her documentary projects included “A Chance at the Beginning,” about a preschool program in Harlem. As David Kamp reports in “Sunny Days: The Children’s Television Revolution That Changed America” (Simon & Schuster), both Cooney and Morrisett were caught up in Lyndon Johnson’s vision of a Great Society, his War on Poverty, and the promise of the civil-rights movement, and they’d both been stirred by a speech delivered in 1961 by Newton Minow, President Kennedy’s F.C.C. chairman, which called television a “vast wasteland.” Minow, a former law partner of Stevenson’s, had gone on to rescue Channel 13’s public-broadcast mandate during a takeover bid. At that dinner party, Cooney and Morrisett got to talking about whether public-minded television might be able to educate young kids.

Educational television for preschoolers seemed to solve two problems at once: the scarcity of preschools and the abundance of televisions. At the time, half of the nation’s school districts didn’t have kindergartens. To address an achievement gap that had persisted long after Brown v. Board of Education, it would have been better to have universal kindergarten, and universal preschool, but, in the meantime, there was universal television. “More households have televisions than bathtubs, telephones, vacuum cleaners, toasters, or a regular daily newspaper,” Cooney noted in a Carnegie-funded feasibility study, “The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education.” With that report in hand, Morrisett arranged for a million-dollar grant that allowed Cooney to begin development of a show with no other title than “Early Childhood Television Program.” In a fifty-five-page 1968 proposal, “Television for Preschool Children,” Cooney reported the results of a national study of the increasingly sophisticated scholarship on child development: she’d travelled the country, interviewing scholars and visiting preschools to find out about what was called, at the time, the “sandbox-to-classroom revolution”—the pressing case for intellectual stimulation for three-, four-, and five-year-olds.

That proposal brought in the eight million dollars in foundation and government funding that made possible the founding of the nonprofit Children’s Television Workshop and the production of the first season of the still unnamed “Early Childhood Television Program.” “Nothing comparable to such a program now exists on television,” Cooney observed. “Captain Kangaroo,” broadcast on CBS beginning in 1955, had educational bits, but it was mainly goofy. (Bob Keeshan, who played the captain, had started out as a Sideshow Bob clown named Clarabell on “Howdy Doody” and then starred as Corny the Clown on ABC’s “Time for Fun.”) “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood,” a half-hour show produced by WQED, in black-and-white, had gone national in 1968, but reached mainly a middle-class audience. The new show would be broadcast nationally, every weekday, for an hour, in color; it would be aimed at all children, from all socioeconomic backgrounds; it would be explicitly educational, with eight specific learning objectives drawn from a list devised by experts; and its format would be that of a “magazine” made up of “one- to fifteen-minute segments in different styles”—animation, puppetry, games, stories. The “Early Childhood Television Program” would also be an experiment: its outcome would be measured.

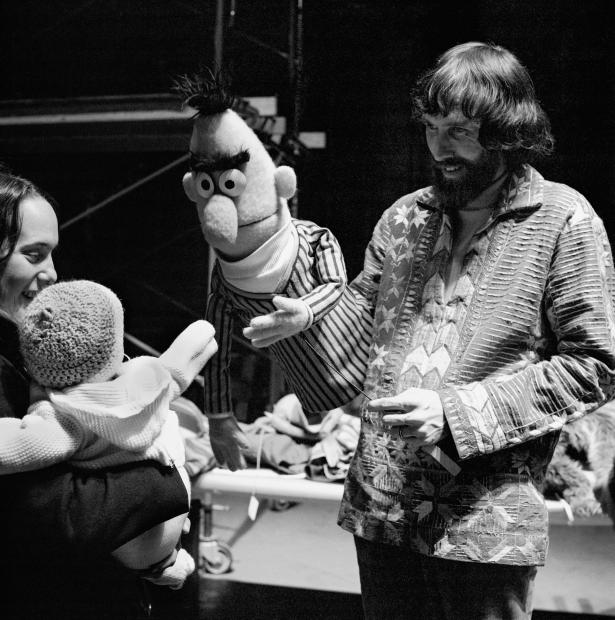

Cooney put together a board of academic advisers, chaired by the developmental psychologist Gerald Lesser, and in 1968 she began a series of seminars loosely affiliated with the Harvard School of Education, where Lesser was a professor. To one of those seminars, she later recalled, “this bearded, prophetic figure in sandals walks in and sits way at the back, ram-rod straight, staring ahead with no expression on his face.” She thought that he might be a member of the Weather Underground. She whispered to a colleague, “How do we know that man back there isn’t going to throw a bomb up here or toss a hand grenade?”

“Not likely,” he said. “That’s Jim Henson.”

Henson—along with Kermit—had got his start on “Sam and Friends,” a puppet-centric show broadcast on an NBC affiliate in Washington, D.C., beginning in 1955. Other puppets on television performed on puppet stages. Among the many features of Henson’s lavish genius was his understanding that the television screen itself was a perfect puppet stage. “Sam and Friends was to the Muppets what the Cavern Club was to the Beatles,” Michael Davis wrote in his 2008 book, “Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street.” The Muppets were witty and edgy, more Beat than square. Kermit appeared on the “Tonight Show” in 1957. But, four years later, “Sam and Friends” went off the air: Henson and his Muppets had outgrown it. Henson turned to making documentaries and films and commercials, as avant-garde as you could get with eyes made out of Ping-Pong balls. In 1968, “The Itty-Bitty, Farm and City, Witty-Ditty, Nitty-Gritty, Dog and Kitty, Pretty Little Kiddie Show” was not what he had in mind for his next career move.

Cooney hired a lot of her talent from “Captain Kangaroo,” including Jon Stone, who would produce and direct the new show. It was Stone who had brought Henson to the seminars. “If we can’t get Henson,” Stone’s team said, “then we just won’t have puppets.” In negotiations, Henson drove a hard bargain. He wanted to retain all rights to his Muppets and split any merchandising from the characters, fifty-fifty, with the Children’s Television Workshop. Henson signed on, and brought on a team that included Frank Oz, who performed Bert, Cookie Monster, and Grover, and Caroll Spinney, who had played a lion on Boston’s “Bozo’s Circus,” and now took on the roles of Oscar the Grouch and Big Bird, a character modelled on an easily flustered four-year-old who needs a lot of help. But Henson brought more than Muppets to “Sesame Street”: he produced many of the show’s “inserts,” the short films that work like commercials. And it was Henson who put into the pitch reel the running gag about the show’s having no title.

The bit was a sendup, but there had been a real battle about the title over at the Children’s Television Workshop, where everyone had been required to come up with a list of twenty names. None of them worked. Stone suggested “123 Avenue B.” The main stage, after all, was supposed to be a brownstone-lined city street, and, as Rowlf told Kermit in the pitch reel, “The idea is to teach little preschool kids some stuff that’ll be useful to them in school, like numbers and letters, and like that.” (Kermit cocked his green head: “And your idea is that the kids are gonna race in from baseball and turn on the educational-TV channel to be taught letters and numbers, hmm?”) But “123 Avenue B” got struck down: too New York.

In the smoke-filled boardroom at the end of a long day, the network executives’ clothes have grown rumpled and the table is heaped with crumpled pieces of paper.

Finally, one Muppet executive has an idea:

“Hey, these kids can’t read or write, can they?” he asks, with the oily voice of a villain.

The other Muppets murmur their assent.

“Then howzabout we call the show ‘Hey, Stupid!’ ”

This was Henson’s swipe at the vapidity and condescension of earlier children’s television shows, from “Ding Dong School” to “Howdy Doody” and “The Mickey Mouse Club,” and at the kind of show that do-gooding foundations had imagined targeting, exclusively, to disadvantaged kids. (“What are they going to call it?” Cooney, wanted to know. “ ‘The Poor Children’s Hour’?”)

“ ‘Hey, Stupid!’?” Rowlf yowls, incredulous. “O.K., that does it! Out, you guys, out!”

The dog despairs—“Who’s gonna find us a title now?”—until the frog croaks, “Hey, Rowlf, why don’t you call your show ‘Sesame Street’? . . . You know, like ‘Open Sesame’? It kind of gives the idea of a street where neat stuff happens.”

“Kermit, why, you’re a genius!”

In fact, the idea hadn’t gone over that well at the Children’s Television Workshop, since, as one wisecracker pointed out, a good part of the show’s audience—kids losing their baby teeth—would only be able to say, “Theth-a-me Threet.” That, it turned out, was a price the Children’s Television Workshop was prepared to pay.

“Sesame Street” débuted on PBS stations across the country on November 10, 1969, four months after Apollo 11 landed on the moon, and about six months before the U.S. invaded Cambodia. “Brought to you today by the letters ‘W,’ ‘S,’ and ‘E,’ and by the numbers 2 and 3,” the show was actually underwritten by grants from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (established by the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967), the U.S. Department of Education, the Ford Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation.

Both NBC and CBS had turned down the chance to broadcast the show. But, a week before its launch, NBC, in an act of surprising public-spiritedness, ran a half-hour preview, “This Way to Sesame Street,” hosted by Ernie and Bert from their basement apartment. “It’s gonna be on the air every day for a whole hour, and in some places it’s going to be on twice a day, twice a day, Bert,” Ernie says, holding up two fuzzy orange fingers.

The original “Sesame Street” has some of the campiness and Pop-art punchiness of the “Batman” TV series, broadcast on ABC from 1966 to 1968. It’s got the pace and variety and kookiness of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” which made its début only weeks before “Sesame Street.” And through it all runs a deep vein of earnestness, especially embodied in the human characters, assembled from a cast led by Matt Robinson. He had been hired as a producer and a coördinator of the show’s live-action films but was recruited to play Gordon, a human character named for Gordon Parks. (Robinson’s very young daughter, watching the first episode back home, cried and said, “His name’s not Gordon, his name is Daddy.”)

Within weeks, “Sesame Street” was a cultural phenomenon. A 1970 New Yorker cartoon: “Why isn’t that child at home watching ‘Sesame Street’?” a street cop asks the mother of a little girl feeding pigeons in the park. TV Guide declared in 1971 that “Sesame Street has enjoyed what may be the most astonishing success of any show in the whole history of American television.” The Times critic Jack Gould predicted, “When the Educational Testing Service of Princeton, New Jersey, completes its analysis in the months to come, ‘Sesame Street’ may prove to be far more than an unusual television program. On a large scale, the country’s reward may be a social document of infinite value in education.”

To an astonishing degree, that turned out to be true. A recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, following up on the original E.T.S. assessment by looking at longer-term outcomes, described “Sesame Street” as “the first mooc.” But that description sells the show short; massive open online courses, like other kinds of “remote teaching,” are mainly an educational catastrophe. Children all over the world have been shut out of their schools by the covid-19 crisis, and, one fears, are learning very little on Google Hangouts and in Zoom classrooms. The story was different with “Sesame Street.” For kids who were under six in 1969, watching “Sesame Street” had a measurable effect on what is known as “grade for age” status: they entered school at grade level, and, in elementary school, they stayed on grade level, an effect that, the study concluded, “was particularly pronounced for boys, black, non-Hispanic children, and those living in economically disadvantaged areas.” And it cost only five dollars per kid per year.

One of the best things about early “Sesame Street” was how well it responded to its critics. When the show started, it had no Latino characters. After a series of protests from the Puerto Rican and Chicano communities, including a press release denouncing the Children’s Television Workshop’s “racist attitude,” Cooney brought in a Latin-American advisory committee and, in its third season, added the characters of Maria (played by Sonia Manzano, who’d just graduated from Carnegie Mellon) and Luis (Emilio Delgado, an actor from L.A. and a longtime Chicano activist), who became the heart of the cast for decades. A grant from the Department of Education funded a Spanish-language version of the show, but “Sesame Street” also decided to just make the program bilingual. In 1972, after a letter-writing campaign by the National Organization for Women, following an Op-Ed in the Times that described “Sesame Street” as “a world virtually without female people,” new people, and new Muppets, moved onto the street. And when initial testing revealed that the show’s reach into the urban neighborhoods it most wanted to reach was limited, the cast was sent on a national tour to build interest in targeted cities. The outreach worked.

Early “Sesame Street” came in for criticism from the right, too. In May of 1970, just after the fatal police shootings at Jackson State College, Mississippi’s State Commission for Educational Television voted to ban the show, objecting to its integrated cast. A character introduced by Robinson, the actor who played Gordon, also led to controversy. Robinson had come out of the Black Arts Movement and was among those who complained to Cooney that Sesame Street was “more Westchester than Watts.” None of the Muppets read as black, so Robinson and Henson created a purple Muppet kid named Roosevelt Franklin. Franklin was such a prodigy that he ran his own elementary school. But he also talked in black English. This led to such a bitter fight between black anti-Roosevelt and pro-Roosevelt factions that Robinson left the show after the third season. But not before Roosevelt Franklin made an album of spoken poetry. “Take a listen to me talking,” he says. “I like the way I talk. Yes, I do.”

Despite the show’s rocky start, those early episodes are still the best television ever made for young children. The magnificence of its achievement was summed up by this magazine’s film critic Renata Adler, in 1972: “It is as though all the lessons of New Deal federal planning and all the sixties experience of the ‘local people,’ the techniques of the totalitarian slogan and the American commercial, the devices of film and the cult of the famous, the research of educators and the talent of artists had combined in one small television experiment to sell, by means of television, the rational, the humane, and the linear to little children.” It doesn’t get any better than that.

Emily Kingsley had worked odd jobs in television production until, in 1970, she was hired by “Sesame Street” as a writer. She went on to win twenty-three Emmys. In 1974, she gave birth to a boy, Jason, with Down syndrome. He started showing up as a guest when he was a toddler, and eventually appeared in fifty-five episodes. He helped Ernie spell words that end with “at.” He counted in English; he counted in Spanish. Watching Jason reading the word “love” with Cookie Monster, letter by letter, is as sacred as some sacraments. “Sesame Street” broke a public silence on Down syndrome twelve years before ABC began broadcasting “Life Goes On,” the first television show to feature a character (and actor) with Down syndrome. “I went for broke,” Kingsley later recalled. “I said, ‘If we can put on Jason, why can’t we put on a whole lot of other kids with disabilities?’ ” Following Kingsley’s initiative, “Sesame Street” characters and Muppets and guests have included deaf kids (the show also teaches sign language) and kids in wheelchairs. Tarah Schaeffer, who has osteogenesis imperfecta, joined the cast in 1993, when she was nine. A lot of viewers still remember when she sang “The Wheels on My Wheelchair” to the tune of “The Wheels on the Bus,” on her way down the sidewalk to join a basketball game. In a more recent milestone, Julia, a yellow Muppet with autism, joined the show, in 2017. She and Big Bird got to be good friends. (Julia, though, later became the subject of contention. Last year, an autism-advocacy group that had helped develop the character cut ties with “Sesame Street.”)

“Sesame Street” sparked a revolution in children’s television, David Kamp argues, but those changes didn’t last. “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood” stopped making new episodes in 1975. “The Electric Company,” another production of the Children’s Television Workshop, shut down in 1977. Meanwhile, at “Sesame Street,” Henson felt trapped. “I am living my own worst nightmare,” he told Cooney, before leaving to launch “The Muppet Show,” in 1976. For Kamp, “Sesame Street” peaked in 1983, after the death of Will Lee, the actor who played Mr. Hooper, the neighborhood grocer. Lee, a former member of a radical theatre troupe, had been called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in the nineteen-fifties and been blacklisted from television; “Sesame Street” had become his theatrical home. He was much admired by the rest of the cast, and the writers decided to reckon, on air, with grief. Big Bird, told that Mr. Hooper is dead, wants to know when he’s coming back. “Big Bird, when people die they don’t come back,” a cast member says, softly. Big Bird tilts his head, yellow feathers fluttering, and whispers, unbelieving, “Ever?”

That episode was a high point. The Reagan years marked the beginning of the fall. The federal government all but stopped funding educational television in 1981, and deregulation meant that the F.C.C. accepted “The Flintstones” as fulfilling a station’s “educational” requirement. Kids’ TV in the nineteen-eighties involved mainly plastic toys: “My Little Pony ’n Friends,” “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” “Sesame Street” became more commercial. Stone complained, from retirement, that a new, gentrified set redesign in 1993 made it look “more like the South Street Seaport than 127th Street.” “Barney and Friends” came out in 1992, not many years after a Barney-like Elmo came to Sesame Street, a place that had gotten, as Sonia Manzano put it, a whole lot “more cutie-pie.” As Kamp observes, “Sesame Street” has become “essentially an expanded, extravagantly art-directed Elmo’s World.”

It’s not that the show isn’t still ambitious. It’s that it’s become hostage to its own ambition. “Sesame Street is the most extensively researched television program in history,” according to “The Sesame Effect,” a 2016 collection of essays by a team of researchers from the Sesame Workshop (the successor to the Children’s Television Workshop). That’s why “Sesame Street” tends to follow ed-school fads. A stem curricular initiative became, right on schedule, a steam initiative (with an “A” for “arts”). Story lines, contorted to fit these fads, have grown more and more contrived. In one episode, the cast had to figure out how to use a pulley to lift Mr. Snuffleupagus into the air as part of the Dance of the Six Swans. Then there was the infamous cookie kerfuffle, in which, in response to the childhood-obesity epidemic, the show’s producers decided to give Cookie Monster an epiphany: “Cookies are a sometimes food.” Right-wing conspiracy theorists claimed that liberal, egghead vegetarians had renamed him Veggie Monster. Cookie Monster went on the “Today Show” and “The Colbert Report” to mock his critics. But there was actually something weirder behind the recasting of Cookie Monster, which had to do with an interest in addressing A.D.H.D. As reported in “The Sesame Effect,” “Cookie Monster was selected to learn self-control and model self-regulation strategies to build executive function skills.” Really? Cookie Monster?

Some of the show’s more recent diversity-and-inclusion efforts have been controversial, and its definition of diversity and inclusion has its own limits (rural poverty and religion have little place on the American “Sesame Street,” for instance). In 2011, Sesame Workshop introduced a Muppet named Lily, whose family struggled with hunger and, later, homelessness; in 2013, Alex, whose father is in prison; in 2019, Karli, a child who has been placed in foster care because her mother suffers from addiction. In the sixties, the creators of the original “Sesame Street” had a heated debate about whether to confront the grimmer realities of the lives of some of their viewers—drug use, gun violence, police brutality, domestic abuse—and decided against it. They chose, instead, to make the street look real, a little grimy, a little raggedy, but with problems like when Ernie eats cookies in bed, and Bert tells him he’ll make a mess, so Ernie decides to eat his cookies in Bert’s bed. This “Sesame Street” is not in the same neighborhood as that one.

“Sesame Street” is now seen in more than a hundred and seventy countries, mainly through co-productions, aided by the Sesame Workshop but run in-country by what the Workshop refers to as “indigenous” production teams of educators, artists, musicians, writers, and puppeteers. “Our producers are like old-fashioned missionaries,” Cooney said in a 2006 documentary, “The World According to Sesame Street.” “It’s not religion they’re spreading, but it’s learning, and tolerance.” If this has led to charges of cultural imperialism—many co-productions, including “Sisimpur,” in Bangladesh, were funded, in part, by U.S.A.I.D.—those charges are generally belied by the actual productions. “Internationalism doesn’t mean you must copy the rich country,” the Bangladeshi puppeteer Mustafa Monwar has said, of a Dhaka-based production for which local set designers built a rural street set under a banyan tree by a tea shop. “Sisimpur” follows the “ ‘Sesame’ model”: educators meet with a creative team to develop the curriculum, whose effectiveness is subsequently assessed through testing. But the circumstances are fundamentally different from those in the United States in 1968: seventy per cent of Bangladesh’s population is rural, and fewer than half can watch television. “Sisimpur” sends out televisions on rickshaws, for kids in villages to watch.

“This is corrupt to the point of perversion,” Patrick Buchanan ranted on cable television in 2002, when “Takalani Sesame,” a South African co-production, introduced Kami, a furry yellow Muppet who is H.I.V.-positive. Developed at the insistence of South African television for a preschool curriculum about the disease, Kami was hugely successful in educating kids, and their families, about H.I.V.-aids. “Kami, we are not scared to play with you, because we know that we cannot catch H.I.V. just by being your friend,” another Muppet says to her. In 2016, Afghanistan’s “Baghch-e-Simsim,” now in its seventh season, introduced a purple Muppet named Zari, a six-year-old Muslim girl. (Americans have petitioned for a Muslim character to be added to the American show.) This winter, the Sesame Workshop, in tandem with the International Rescue Committee, launched one of the largest early-childhood interventions in the history of humanitarianism: “Ahlan Simsim,” an Arabic-language show designed to help millions of children who are refugees.

Abroad, “Sesame Street” is still driven by the spirit of 1968. In the U.S., that spark has gone. The Muppets were sold to Disney, after which the Disney Channel launched a sickening remake of the Henson series “Muppet Babies,” a show so merchandise-driven that wittle, itty-bitty, never-witty Baby Kermit might as well talk with a price tag hanging off his face. Since 2015, “Sesame Street” has been released first not on PBS but on HBO. A show designed as a public service, part of the War on Poverty, is now one you’ve got to pay for. In a staggering betrayal of the spirit of the show’s founding philosophy, last year’s fiftieth-anniversary special appeared on HBO before it was broadcast on PBS. This month, HBO Max is launching “The Not-Too-Late Show with Elmo.” A few years back, if you bought DVDs of any of the first five seasons of “Sesame Street” they came with a disclaimer: “These early ‘Sesame Street’ episodes are intended for grown-ups and may not suit the needs of today’s preschool child.” Or these anthology editions could just have been given a different title: “Hey, Stupid!”

“Stay home!” Oscar the Grouch says in a recent covid-19 public-service announcement. “I don’t want to see your smiling face!” It’s not funny. It’s not sweet. It isn’t even delightfully grouchy. It’s just shtick. Honestly, it’s enough to send you to bed with a box of cookies. “I was just hungry, Bert. So I thought I’d have a few cookies before I go to sleep.” Good night, Ernie. ♦

An earlier version of this article misstated the title of a documentary project by Joan Ganz Cooney, as well as certain details about the Muppets Julia, Elmo, and Lily and the shows “Sisimpur,” “Ahlan Simsim,” and Disney’s “Muppet Babies”; and wrongly dated “Sesame Street” ’s début in relation to the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, and the broadcast schedule of the fiftieth-anniversary special.

Published in the print edition of the May 11, 2020, issue, with the headline “When Ernie Met Bert.”

Jill Lepore is a professor of history at Harvard and the host of the podcast “The Last Archive.” Her fourteenth book, “If Then,” will be published in September.

Spread the word