On Tuesday, Judge Amy Coney Barrett took a few minutes during her confirmation hearing to discuss her judicial philosophy, best known as originalism. It means, she explained, “that I interpret the Constitution as a law, I understand it to have the meaning that it had at the time people ratified it. That meaning doesn’t change over time and it is not up to me to update it or infuse my policy views into it.”

Now, originalism is subject to a good deal of criticism and critique as a method for decoding the Constitution. Zeroing in on its narrow preoccupation with language, Jonathan Gienapp, a historian of the early American republic at Stanford, charges originalists with building a framework “such that no amount of historical empiricism can ever challenge it,” in which neither “the Framers’ thoughts or agendas or the broader political, social, or intellectual contexts of the late eighteenth century” have any bearing on the so-called original public meaning of the Constitution.

Likewise, the historian Jack Rakove, also at Stanford, argues in a 2015 paper, “Tone Deaf to the Past: More Qualms About Public Meaning Originalism,” that the events of the American Revolution put “sustained pressure” on critical terms like “constitution” or “executive power” that cannot be understood without a historical understanding of this political and intellectual tumult. “Anyone who thinks he can establish conditions of linguistic fixation without taking that turbulent set of events into account is pursuing a fool’s errand,” Rakove writes.

But today, at least, I don’t want to challenge originalism as a method as much as I want to ask a question: When we search for the original meaning of the Constitution, which Constitution are we talking about?

Barrett’s Constitution is the Constitution of 1787, written in Philadelphia and made official the following year. That’s why her formulation for originalism rests on ratification, as she states at the outset of a paper she wrote called “Originalism and Stare Decisis.”

Originalism maintains both that the constitutional text means what it did at the time it was ratified and that this original public meaning is authoritative. This theory stands in contrast to those that treat the Constitution’s meaning as susceptible to evolution over time.

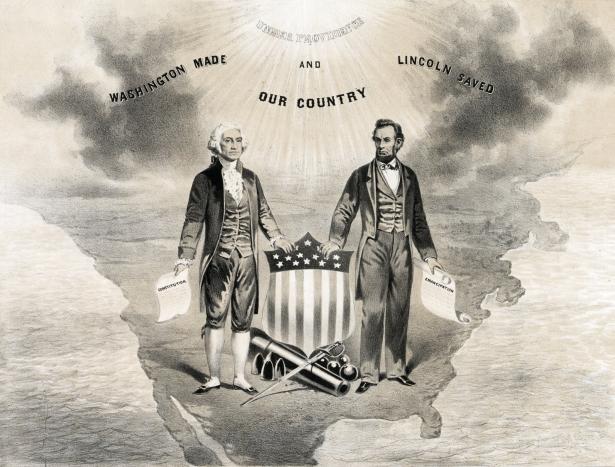

Many Americans think the same, identifying the Constitution with the document drafted by James Madison to supplant the Articles of Confederation and create more stable ground for national government. But there’s a strong argument that this Constitution died with the attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

The Civil War fractured an already divided country and shattered the constitutional order. What came next, Reconstruction, was as much about rebuilding that order as it was about rebuilding the South. The Americans who drafted, fought for and ratified the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments did nothing less than rewrite the Constitution with an eye toward a more free and equal country. “So profound were these changes,” the historian Eric Foner writes in “The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution,”

that the amendments should not be seen simply as an alteration of an existing structure but as a “second founding,” a “constitutional revolution,” in the words of Republican leader Carl Schurz, that created a fundamentally new document with a new definition of both the status of blacks and the rights of all Americans.

Whereas the Constitution of 1787 established a white republic in which the right to property meant the right to total domination of other human beings, the Reconstruction Constitution established a biracial democracy that made the federal government what Charles Sumner called the “custodian of freedom” and a caretaker of equal rights. To that end, the framers of this “second founding” — men like Thaddeus Stevens, Lyman Trumbull and John Bingham — understood these new amendments as expansive and revolutionary. And they were. Just as the original Constitution codified the victories (and contradictions) ofthe Revolution, so too did the Reconstruction Constitution do the same in relation to the Civil War.

Credit...Erin Schaff/The New York Times

The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, may read like a simple prohibition against slavery, an affirmation of the post-Emancipation Proclamation status quo. But at a time when Americans still conceived of the national government as the principal threat to liberty, the Thirteenth Amendment reframed that government as the principal defender of a new right to personal freedom, derived from the ban on bondage. With its enforcement clause (“Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation”), lawmakers were given seemingly limitless authority to, in the words of the Chicago Tribune at the time, “prevent actions by states, localities, businesses, and private individuals that sought to maintain or restore slavery.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, similarly recast the government as the defender of individual rights, including the right to citizenship. It extended the Bill of Rights to all Americans, guaranteed “equal protection of the laws” and declared that no state “shall abridge the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States,” a phrase understood to include any number of inalienable and fundamental rights claimed by the people but left unarticulated in the Constitution. “The amendment,” Foner writes,

asserted federal authority to create a new, uniform definition of citizenship and announced that being a citizen — or, in some cases, simply residing in the country — carried with it rights that could not be abridged. It proclaimed that everyone in the United States was to enjoy a modicum of equality, ultimately protected by the national government.

As for the Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, it too represented a sweeping expansion of federal power for the sake of equality, announcing that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Where voting rights were once the domain of the states, to be granted (or restricted) as the states desired, they were now guaranteed by the national government. And while the amendment was too limited to prevent Jim Crow voting laws — and left most women disenfranchised for another 50 years — it still opened the space for Congress to protect and expand Americans’ access to the ballot.

The Reconstruction Constitution is a fundamentally different document than the Constitution of 1787. Yet our conversations around “original meaning” rarely take account of this change. Our politics would likely look very different if Reconstruction were the basis for our common constitutional understanding, if founders’ chic included Bingham and Sumner as much as Madison and Benjamin Franklin, and our jurists were preoccupied with bringing the original meaning and intent of those amendments to bear on American life. Here, Ruth Bader Ginsburg stands as a particularly strong example, because she used the Fourteenth Amendment to fight sex discrimination, giving more and greater meaning to the amendment in the process.

For a sense of what this might look like under the other Reconstruction amendments, consider the 1872 case Blyew v. United States, in which the Supreme Court overturned convictions of two Kentucky men arrested and tried for an attack on a Black family that left four people dead. At the time, Kentucky did not allow Black Americans to testify against whites and barred them from jury service, but the Civil Rights Act of 1866 allowed federal prosecutors to move from state to federal courts any case “affecting” persons who had been denied equal treatment in the states. The Court disagreed. By its reasoning, the Black witnesses to the crime were not actually affected by the state’s discrimination. The only affected persons were, instead, the white defendants.

In his dissent, Justice Joseph P. Bradley, an appointee of President Ulysses Grant, rejected this claim that racial discrimination in jury selection was of no larger impact. In doing so, he offered a robust vision for what the Thirteenth Amendment could accomplish. Here’s Foner:

Slavery, Bradley observed, “extended its influence in every direction, depressing and disenfranchising the slave and his race in every possible way.” Abolition meant not merely “striking off the fetters” but destroying “the incidents and consequences of slavery” and guaranteeing the freed people “the full enjoyment of civil liberty and equality.”

If we were to try to build an “original meaning” of the Constitution around the Reconstruction amendments, we might come to this view of the Thirteenth Amendment, which could open the doors to vastly more aggressive federal action to reduce racial discrimination, racial inequality and other “badges and incidents of slavery.” A similar approach to the other amendments would be equally transformative: The “privileges and immunities” of citizenship, for example, might include the right to education and employment. And a Congress fully empowered to secure voting rights could act very aggressively to head off those states that seek to deprive their residents of equal access to the ballot.

To take the Second Founding seriously is to reject a vision that binds us to the Constitution as it was in 1787. It is also to embrace a broader vision of the “framing” of American democracy, one that looks to the reconstruction of the country after its near-destruction as much as to its birth and founding.

As a matter of history, the Constitution is neither fixed in meaning nor in structure; the men who wrote and ratified it disagreed as much about what it meant as we do today. But even if it had a singular meaning, you would still have to make a choice about which Constitution to adhere to, either one written to secure the interests of a narrow elite or one written for the sake of us all.

Jamelle Bouie is an opinion columnist for the New York Times.

Choose from a wide variety of newsletters from the New York Times.

Spread the word