Today was, perhaps astonishingly, the last jobs report of 2020. It’s a moment to take stock of where things stand after the first 11 months of 2020 and the first 9 months of the COVID-19 economic shock.

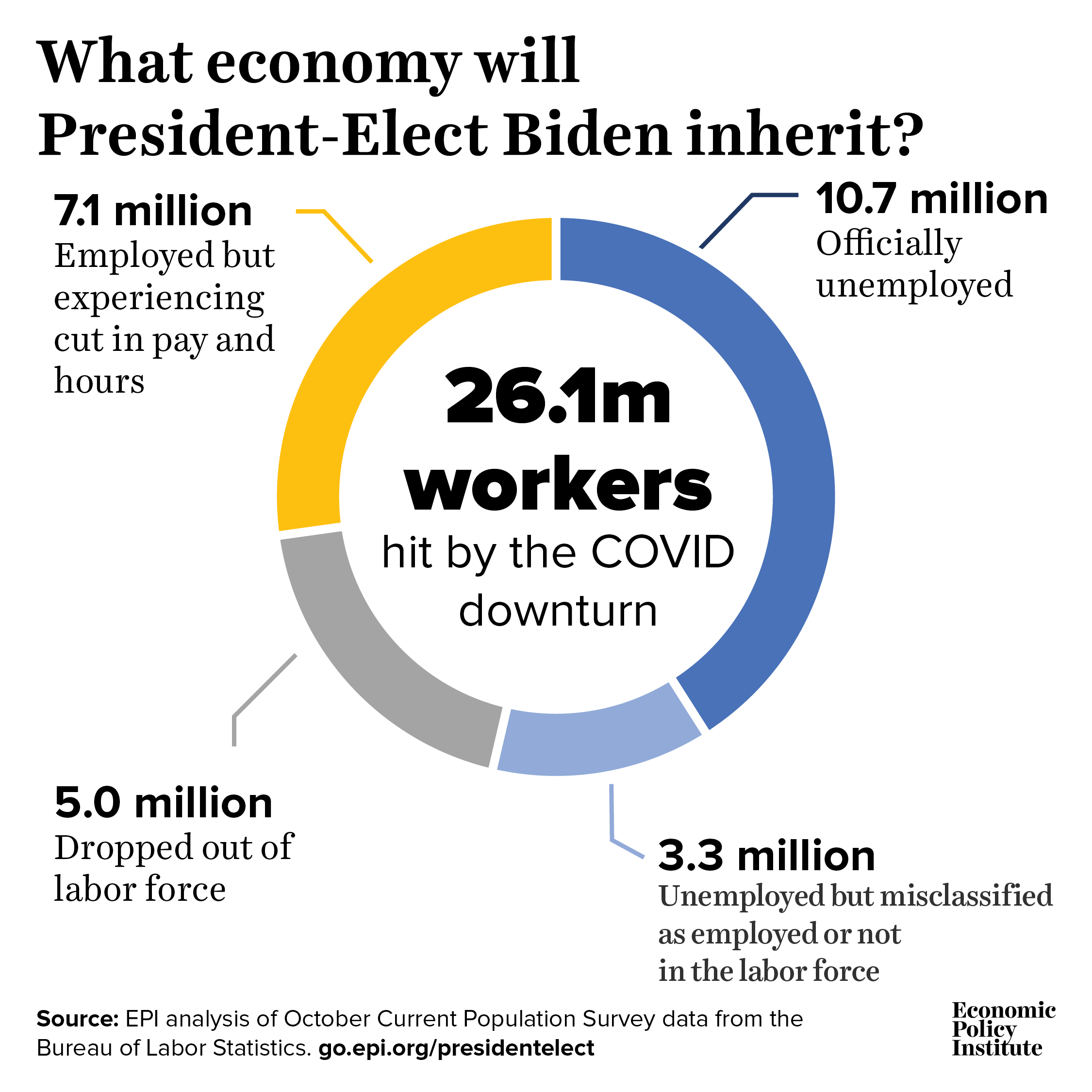

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that the official number of unemployed workers in November was 10.7 million, and the unemployment rate was 6.7%. The official number of unemployed workers, however, is a vast undercount of the number of workers being harmed. In fact, 26.1 million workers—15.5% of the workforce—are either unemployed, otherwise out of work due to the pandemic, or employed but experiencing a drop in hours and pay. Here are the missing factors:

- Some workers are being misclassified as “employed, not at work” instead of unemployed. BLS has discussed at length that there have been many workers who have been misclassified as “employed, not at work” during this pandemic who should be classified as “temporarily unemployed.” In November, there were 0.6 million such workers. (Wonky aside: Some of these workers may not have had the option of being classified as “temporarily unemployed,” meaning they weren’t technically misclassified, but all of them were out at work because of the virus.) Accounting for these workers, the unemployment rate would be 7.1%.

- The number of officially unemployed is undercounted, even in normal times (and is probably worse now). Rigorous research that addresses issues like the fact that survey nonresponse is nonrandom—and that missing individuals are more likely than the general population to be unemployed—finds that the official unemployment rate was understating the unemployment rate by 1.5 percentage points at the start of 2020. Accounting for that undercount yields 2.7 million unemployed workers who are misclassified as not in the labor force. This is conservative, given that there is good evidence that this problem is likely substantially worse in the coronavirus era. (Wonky aside: This research also finds that the official labor force participation rate was understating labor force participation by 1.9 percentage points at the start of 2020, or 4.8 million workers.)

- Some workers who are out of work as a result of the virus are being counted as having dropped out of the labor force instead of as unemployed. In order for a person without a job to be counted as unemployed, they must be available to work and actively seeking work. However, during the COVID-19 crisis, many people who are out of work as a result of the crisis do not meet those criteria. For example, many workers are out of work because of care responsibilities as a result of COVID-19 (e.g., a young child’s school being remote or an elderly parent’s day care closing). These workers would not be counted as officially unemployed but are nevertheless out of work because of the virus. To calculate how many there are, I estimate what the labor force level would be if the labor force participation rate had not dropped since February—the month before the pandemic hit the U.S. labor market—by multiplying the February labor force participation rate by the November population level. I then subtract this “counterfactual” labor force from the actual labor force. This yields an additional 5.0 million people out of the labor force as a result of the virus.

- Millions of employed workers have seen a drop in hours and pay because of the pandemic. BLS reports that 7.1 million people who were working in November had been unable to work at some point in the last four weeks because their employer closed or lost business due to the coronavirus pandemic, and they did not receive pay for the hours they didn’t work. These workers have clearly been directly harmed by the coronavirus recession.

Adding up all except the last quantity above, that is 10.7 million + 0.6 million + 2.7 million + 5.0 million = 19.0 million workers who are either officially unemployed or otherwise out of the labor force as a result of the virus. Accounting for these workers, the unemployment rate would be 11.2%. Also adding in the 7.1 million who are employed but have seen a drop in hours and pay because of the pandemic brings the number of workers directly harmed in November by the coronavirus downturn to 26.1 million. That is 15.5% of the workforce.

Finally, even the 26.1 million is an undercount. For one, it doesn’t count those who lost a job or hours earlier in the pandemic but are back to work now. The cumulative impact would be much higher. But perhaps more importantly, the 26.1 million is a drastic undercount because it ignores the fact that even workers who have remained employed and have not seen a cut in hours are being hurt by the recession. How? Essentially the only source of power nonunionized workers have vis-à-vis their employers is the implicit threat that they could quit their job and take another job elsewhere. Case in point: One of the most common ways nonunionized workers get a wage increase is by getting another job offer for higher pay—they either accept the new job, or their current employer gives them a raise in response to their outside offer. When job openings are scarce, as they are now, workers’ leverage dissolves. Employers simply don’t have to pay as well when they know workers don’t have as many outside options.

All this means that stimulating the economy to create jobs is crucial—both to the 26.1 million workers who are being directly harmed by the recession because they are either out of work or have had their hours and pay cut, and to the millions more who saw their bargaining power disappear as the recession took hold. This is a preventable disaster for the workers of this country. Extending the unemployment insurance (UI) provisions of the CARES Act and providing fiscal aid to state and local governments could alone create or save millions of jobs over the next year (just the pandemic UI provisions could create or save 5.1 million jobs). To get the economy back on track in a reasonable timeframe, we need policymakers to pass roughly $3 trillion in fiscal support now, with the first $2 trillion hitting the economy between now and mid-2022. However, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has so far blocked additional meaningful COVID-19 relief. As the country faces slowing job growth and a resurgent virus, it is outright economic sabotage to block emergency relief when millions are depending on it most. McConnell cannot continue to stand in the way of desperately needed relief.

Spread the word