Why are we still listening to, and indeed writing about, Ludwig van Beethoven? Two centuries have passed since his music was written and first performed. Even his most esteemed contemporaries, such as Joseph Haydn, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Franz Schubert, have not been as consistently popular, nor had their music as much analyzed and reinterpreted.

Unlike the music of Gustav Mahler or Anton Bruckner, Beethoven’s has never needed to be rescued from obscurity: it has been a continuous fixture of concert programs since his own lifetime. His music was radical for its time, and even today, there are pieces of his, such as the Grosse Fuge and some of the late string quartets, that remain challenging for the performer and the listener. Yet these pieces have a secure place in the concert repertoire, far outstripping those of modernists like Arnold Schoenberg and Igor Stravinsky.

No other Western classical composer’s music is as much a feature of public events or political propaganda as Beethoven’s. Take one of his most important and famous works, the Ninth Symphony. Performances were organized by trade unions in Germany after World War I, and then during the Third Reich to mark Hitler’s birthday. Rhodesia’s white-supremacist government adopted it as an anthem, and so more recently did the European Union. Leonard Bernstein conducted an orchestra composed of musicians from both East and West Germany as they performed it to mark the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Composer of Modernity

It is not simply a question of his compositions being interesting and beautiful works of art. I adore the music of Haydn and Mozart, but their sound world never makes me feel that I am anywhere other than the late eighteenth century. Listening to many of Beethoven’s works, there are moments or entire spans that feel modern, conjuring up experiences that remain immediate.

This is largely due to the fact that Beethoven witnessed the birth pangs of the modern world. To a degree unmatched by any of his contemporaries, he managed to express the exhilaration and dynamism of that revolutionary period, together with its contradictions, its moments of despair and defeat.

Almost the whole of Beethoven’s life was shaped by the French Revolution and its aftermath. Born in 1770, he was in his late teens when the Bastille was stormed. The revolution reached its zenith with the Jacobins and entered its reactionary phase during his twenties. His letters from this period contain many declarations of support for the revolution, affirming his own self-identification as a democrat.

Beethoven became famous throughout Europe at the same time as Napoleon’s armies laid waste to the old order across the continent. But he also lived through the revolution’s decline and the harsh reaction against it.

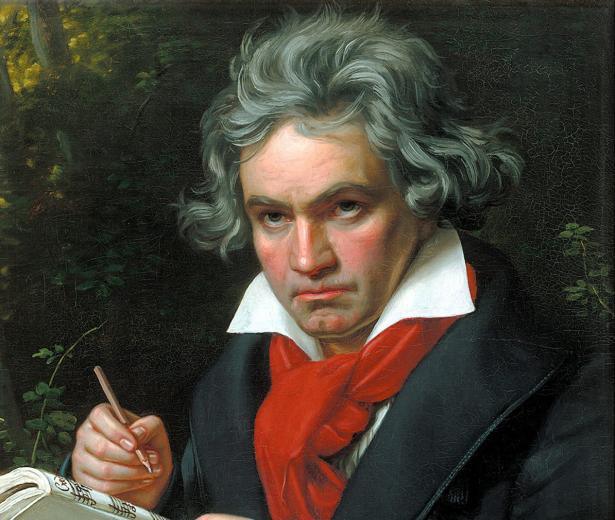

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven in 1803, painted by Christian Horneman.

He experienced two major artistic and personal crises in his life. The first coincided with Napoleon crowning himself emperor, a signal that the republican ideals of the Revolution had been betrayed. The second followed the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, and the triumph of reaction.

The dynamic of these two crises in the revolution was very different, and so was Beethoven’s response to them. Beethoven epitomized the relationship between the artist and the dynamic of revolution, and in this respect, he laid a path that others like Richard Wagner and Dmitri Shostakovich followed.

The “Heroic” Period

In 1802, Beethoven experienced a personal crisis centered on his growing deafness and his deep loneliness. The depths of his despair are clear in a letter to his brothers, now known as the Heiligenstadt Testament. Somehow, he managed to emerge from this trough, and the first work that he wrote afterward was the Third Symphony.

This marks the full emergence of what has become known as the essence of Beethoven’s “heroic” style. It is difficult to overstate how much this piece transformed Western music as a whole. It is conceived on a scale larger than anything that had gone before: the first movement alone is longer than most entire symphonies of the eighteenth century.

The symphonic form had long been one that dealt with tension and struggle. However, in this symphony, these aspects are dramatically accentuated. Rather than a gentle introduction, we get two very loud and abrupt chords, which, in the words of Leonard Bernstein, shattered the elegance of the eighteenth century. The rest of the movement has a sense of constant propulsion, but it is often harmonically unstable — a combination that one finds throughout his mature works.

Famously, Beethoven dedicated this symphony to Napoleon, and then scratched out the dedication on hearing that Napoleon had crowned himself emperor. The final title given to the piece was the Eroica (“The Heroic”).

It is striking that Beethoven expressed his emergence from a deep depression not in an introspective or purely personal way, as became common among the Romantic composers in the nineteenth century, but through the hope offered by the promise of revolutionary change in Europe. Scholars often assume that Beethoven’s belief in revolutionary ideals died with the excising of the dedication to Napoleon, but this is far from being the case. There are many scattered references in his letters throughout his life that suggest he still believed in an end to aristocratic and church power.

Indeed, as late as 1822, when Beethoven heard of Napoleon’s death, he is reported to have said: “I have already composed the proper music for that catastrophe.” It is likely that he was referring to the grand funeral march that is the second movement of the Eroica, although it is also possible that he had in mind the huge setting of the Mass that he was writing at the time, the Missa Solemnis. The evidence of Beethoven’s continued radical sympathies is also there in many works that he produced over the years.

Revolution of Form

In the decade after the Eroica, he produced a series of other masterpieces, including his fifth, sixth, and seventh symphonies; his only opera, Fidelio; several grand overtures; the last three piano concertos; and his Violin Concerto, the Razumovsky quartets, the Appassionata piano sonata; and many others. All of these pieces in one way or another revolutionized musical forms. The pieces for large orchestra and Fidelio often express themes of freedom from oppression.

Fidelio is a leading example of a “rescue opera,” a genre closely associated with the French Revolution, typically involving the rescue of a hero from confinement or execution at the hands of tyranny. The opera is based on a libretto by Jean-Nicolas Bouilly, who had been a leading jurist in the French republican government. Supposedly based on a true story, it concerns a woman who disguises herself as a man in order to help her husband, a political prisoner, escape from prison.

The first performances of the opera were held in Vienna while it was under occupation by Napoleon’s forces. Indeed, the troubled history of this opera, which failed on its first performances and had to be drastically revised for future performances, can perhaps be partly explained by the unpalatability of its more radical political aspects.

Beethoven was far from being the only composer of his time to welcome the French Revolution and to express its ideals in music. Indeed, there were contemporaries who expressed this in far more obvious ways. For example, François-Joseph Gossec, Luigi Cherubini, and Étienne Méhul wrote patriotic songs and operas that explicitly celebrated republicanism. Yet while intellectually these composers celebrated the new, they did so in the style of the old, and that is one reason why their works have not survived the passage of time.

In contrast, Beethoven expressed the dynamism of his times not merely on the surface, with declarations of republican virtue, but rather by developing a radically new musical style that reflected the new times. There are few enough works of his in which the political element is particularly overt — mainly Fidelio, the Eroica, and the Ninth Symphony. Beethoven conjured up sound worlds that, at the time, felt revolutionary. In fact, they radically transformed European music, in much the same way that republicanism was transforming European society.

He achieved this partly through a greater sense of scale, not only in terms of the length of pieces, which required more complex musical architectures, but also in terms of the size of the orchestra, the range of instruments used, and by pushing the technical abilities of musicians beyond what had previously been expected. When one violinist complained to him about the technical difficulty of one of his compositions, Beethoven is said to have replied, “What do I care for your lousy fiddle!”

Stylistically, he had a tendency to focus on tiny, often banal themes that relentlessly drive large expanses of music, but that are passed around the different instruments and constantly transformed. This style is epitomized in the first movement of the Fifth Symphony, which begins with one of the most famous motifs in all of music. Almost every bar of that movement, which lasts for around seven minutes, repeats that motif in some form. Indeed, it appears in the second movement, too, dominates the third, and once again can be heard in the final movement.

This creates a sense of unity and of constant transformation over the entire symphony, rather than being just a succession of movements loosely held together, if at all, which was typical of symphonies up to that time. It is this drive — the heroic scale, the grand narrative, the sense in music of a unity of purpose and radical transformation — that bring a period of revolutionary fervor to life.

Reaction and the Late Period

The second major crisis in Beethoven’s life began around 1813. His younger brother Kaspar died from tuberculosis, and he then became embroiled in a long and unpleasant legal battle with Kaspar’s widow over guardianship of their son. After the succession of masterpieces in the previous decade, his compositional output slumped.

The only large-scale work he was to complete during this period was a piece commissioned to celebrate the victory of Wellington over Napoleon at the Battle of Vitoria. This Battle Symphony is, not to put too fine a point on it, musical trash: bombastic, with a lack of musical development, and sustained by cheap gimmicks such as the use of a newfangled mechanical organ that could reproduce the sounds of battle. It has none of the ambiguities or invention that one hears elsewhere in his work.

Beethoven walking in nature. (Michael Martin Sypniewski / Wikimedia Commons)

And yet it made Beethoven more money than anything else he produced in his life. Perhaps one of Beethoven’s less illustrious “firsts” is the discovery that cheap entertainment often produces greater rewards than revolutionary art under capitalism. But this episode is perhaps further evidence of his deep personal and political demoralization.

Had Beethoven produced nothing else of significance during the remaining fourteen years of his life, he would still be regarded as one of the greats of Western music. Instead, having already been one of those rare people who transforms his art form once, he became that even rarer artist who does it a second time. His “late period” has become a template for many subsequent artists in different fields, as a period in which a recognized genius has the confidence and the ability to extend the horizon of artistic possibilities for generations to come.

There aren’t that many significant pieces from this period. Apart from a number of minor compositions, there is just one symphony, five string quartets, half a dozen piano sonatas, and a setting of the Mass. But each of these pieces remain, more than two hundred years later, among the most important in the history of Western music.

The so-called “Late Quartets” have an emotional depth never heard before in this form, and rarely equaled since. This quality can be heard most strikingly in the String Quartet No. 13. Beethoven’s publisher objected to one movement of this piece, arguing that it threatened its commercial viability. Beethoven published it separately as a stand-alone piece, known as the Grosse Fuge.

The Grosse Fuge baffled critics and audience alike when it was first performed, and even today, it remains a challenge for listeners. A fugue simply involves at least two themes being played off against each other and has been a standard form for composers for centuries. But in this piece, that dynamic is launched with tremendous tension, something that it maintains, with only a brief release, for its entire span of some fifteen minutes. Stravinsky, the arch-modernist of the twentieth century, described it as a piece that would “always remain contemporary.”

For the Whole World

These pieces, along with the Hammerklavier sonata and the Missa Solemnis, suggest that personal hardships and political demoralization had led Beethoven to retreat almost completely into an inner world, far removed from attempts at a dynamic engagement with the world around him that marked the heroic period of the 1800s.

The standard narrative contends that Beethoven had made his peace with political reaction, or at least had put the revolutionary fervor of his youth behind him. But his Ninth Symphony, completed just three years before his death, gives quite the opposite impression.

What is it that makes the Ninth Symphony still so compelling as both a work of art and a political statement? Its opening is unlike any heard before in a major orchestral work. Sounds emerge from somewhere mysterious and diffuse, gradually summoning up the forces of the orchestra. This technique of opening with a “long horizon” would not be fully exploited again until the symphonies of Bruckner and Mahler many decades later.

In the middle of that first movement, there is a cataclysmic passage in which violence and anxiety is expressed with a force and dissonance that presages music of a century later, composed around the time of World War I and the collapse of the European empires. The symphony never quite recovers from that trauma until the climactic “Ode to Joy,” more than half an hour later.

Even then, the triumphant conclusion is hard-won, with unstable harmonies and a set of variations that seem to be continually searching for a final victory. The closing moments of the symphony, while exhilarating and ultimately triumphant, also have a sense of manic desperation.

In short, the entire symphony is a musical exploration of struggle, but this time much more extreme and precarious than in the Eroica of twenty years before. In contrast with many of the Romantics who came after Beethoven, the scale on which the music is written makes it clear that it is not merely a struggle of a solitary person, but one that unfolds on an altogether grander scale.

The words of Friedrich Schiller that are set in the finale make this even clearer, with the declarations that “All men shall be brothers” and “Be embraced, you millions! This kiss is for the whole world!” These sentiments were also very much at odds with a period that saw the restoration of monarchy in France and repression of the republican movement across Europe.

An Earthy Icon

Beethoven died in March 1827. It was estimated that up to thirty thousand people attended his funeral procession in Vienna, a city whose total population was just two hundred thousand at the time. Very soon afterward, deification set in. Monuments to Beethoven such as the one erected in his birthplace of Bonn in 1845, or Max Klinger’s sculpture for the famous Secessionist exhibition of 1902, depict him in the style of a great political leader or a god of antiquity.

Max Klinger’s sculpture of Beethoven for the famous Secessionist exhibition of 1902. (Archive of Secession)

As late as the early twentieth century, composers were still struggling to emerge from his shadow. Beethoven’s name and image have come to represent much more than merely his own life and music: they have become an avatar for the Western classical tradition itself. When Chuck Berry wanted to signal rock ‘n’ roll’s iconoclastic arrival, he did not give his hit single the title “Roll Over Bach.”

And yet, in life, Beethoven was ill-kempt, and on occasion something of a hustler when it came to publishing his works and organizing concerts of his music. He is the first major composer never to have appeared in portraits in a wig, and to have made a living as an independent musician throughout his career, rather than through service to the church or an aristocratic family.

The biggest problem with the Promethean image of Beethoven is that he actually struggled a great deal to produce his masterworks. It is clear from his letters and the testimony of his many friends that he was a very earthy character. That comes through in his music, too, which is often defined by its heroic style, but which also speaks to us at a very human level. Much of his music expresses a time of struggle between hope for radical progressive change and the forces of reaction. That was Beethoven’s world, and in many ways, it is also ours.

Simon Behrman is the author of Shostakovich: Socialism, Stalin & Symphonies.

Subscribe to Jacobin today, get four beautiful editions a year, and help us build a real, socialist alternative to billionaire media.

Spread the word