Adrian Miller is a food writer, James Beard Award winner, attorney, and certified barbecue judge who lives in Denver, Colorado. Miller’s first book, Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisinee, One Plate at a Time won the James Beard Foundation Award for Scholarship and Reference in 2014. His second book, The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, From the Washingtons to the Obamas was published on President’s Day 2017. It was a finalist for a 2018 NAACP Image Award for “Outstanding Literary Work – Non-Fiction,” and the 2018 Colorado Book Award for History. Adrian’s third book, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue, will be published spring 2021.

This interview, held on November 19, has been edited and condensed for clarity. On the cutting room floor: the specifics of a certified barbecue judge’s badge, Quaker cooking, and how long it takes to trademark slogans (long).

Sarah: You describe yourself as “a recovering lawyer and politico.” What were those past lives like for you?

My professional goal, really, was to be in the United States Senate representing Colorado. I went to law school, but then when I practiced law, I just hated it, and it got to the point where I was singing spirituals in my office [Sarah laughs], so I figured I should do something else.

I was going to open up a soul food restaurant. I’d always liked to cook. But I got a fateful call from a friend who was working for President Clinton on the Initiative for One America, which had the bold and crazy idea that if we talked to one another and listened, we might realize we got a lot more in common than what supposedly divides us.

She reached out and asked if I had friends back in D.C. who might want to work at the White House. When she explained the job to me, I said, “I’ll take that.” I applied and got it, so I moved to D.C. to be a part of it.

After the Clinton administration ended, I was trying to get back to Colorado to start my political career, but the job market was really slow. I was basically unemployed, watching a lot of daytime television, and I said, “You know, I should read something.” [Sarah laughs.] I went to a local bookstore, and I found this book on the history of Southern food written by John Egerton. In that book, Mr. Egerton wrote that the tribute to African American achievement and cookery had yet to be written.

I reached out to him and asked if he thought that was still true (I picked up the book in 2001), and he said, “For the most part, nobody’s really taken on the full story.” So with no qualifications at all, except for eating and cooking a lot of soul food, that put me on a journey to write a book on the history of soul food.

As you know, you don’t really live off writing, or a lot of us don’t. I came back to Denver and had a job in a progressive think tank, then I ended up working for Colorado’s governor. At the same time, I worked on the book on weekends and after work.

After the governor decided not to run for re-election, I said, “I’m just gonna go for it.” I knew otherwise that I would be working on it on the side forever. I cashed in my retirement savings, and I lived on that to write the book. The book came out in 2013, and then I got my current job as the executive director of the Colorado Council of Churches. It’s a part-time job, so I’m able to still do writing and have a quote-un-quote day job.

I was reading your biography online, and there’s such a strong throughline of religion and faith in your life. How does your faith inform your approach to food?

My faith instructs that we should love one another, and that I should love every person because they are an image of God. There’s something good about everybody, even though they make it hard for you to see that.

I hate to see discord, the amount of hatred and violence we see in our world, and at least in the United States, the divisions are getting so deep that we have fewer and fewer spaces where we can come together. Food, I think, is one of those tools that can create an inviting space, because we all have to eat.

Cooking is an act of love—basically, the cook is saying that they care for your survival, even if the food is straight nasty. [Sarah laughs.] It’s been my experience that when people sit down to eat, you recognize the humanity of the other person. Often the food, especially if it’s good, can facilitate conversation and start to break down barriers.

For those who go to church, it’s one of the few spaces we have left where people from all kinds of walks of life can come together in a space on a regular basis.

I was raised Quaker, and a big thing in my Quaker meeting was potlucks. I remember, though, that none of the food was that good. [Sarah and Adrian laugh.]

I’m a little surprised the food wasn’t that good.

I was surprised as well. I was always hoping that by the next iteration, someone would have picked up a cookbook or stepped up their game, but it never happened. [Adrian laughs.]

Did you grow up in a family with a culture around food?

That was definitely my experience. My dad can cook, but my mom was the primary cook, and she was a very good cook. Not only was she good at making soul and Southern food, she was pretty good at making foods from other ethnic genres, as well as Americana, so I grew up with a really good cook. I got to learn some of what she did before she died, so I feel really fortunate.

In an interview with Sankofa Farms, you said, “A lot of my work is to look at our food, to celebrate it, but also to celebrate the people, the African Americans who have done so much to contribute to our foodways.” I looked up Sankofa and the Ghanian proverb it’s associated with, which Wikipedia translated as: “It is not wrong to go back for that which you have forgotten.” In your work, what do you feel you’re going back for?

I’m going back for that connection to Africa. So much of African American history has been forced dissociation from Africa by whites—not only those who enslaved African Americans, but those who were complicit in it.

When I was about 7 or 8, Roots was on TV. At school, our teachers asked us to trace our roots. I just remember people going around the room and they could say, “Oh I’m ⅛ Irish, ¼ Scottish,” and I could not say that. All I could say was African American. I knew I was from Africa, but I couldn’t tell you a country.

I think this is common with a lot of African American families, where some people don’t want to talk about what happened in the past, because there was rape, unacknowledged rape and other things. That past is painful. That clearly was the case on my father’s side of the family: Somewhere along the line, somebody raped someone, and never acknowledged or owned up to what they did.

So in the tatters of what has been wrought because of the status of Black people in this country, I’ve been very interested in finding the clues of what we brought from Africa and what has been resilient and still manifests itself today, even if it’s in a form we don’t recognize because we’re just not familiar with it anymore.

I’ve been fascinated by making those connections—so, showing foods from Africa that get embraced here in the United States and how they play out, and maybe how they’re similar to dishes in Africa. You can see there’s a cultural continuity.

Over the years you’ve been researching and publishing these books, do you feel that that cultural conversation has strengthened? Do you feel that people are coming to your work now with a little more fluency, as it were?

I think one of the cool things that’s happened in the last few years is that you have more people in the conversation now. I think there’s much more interest in this idea of culinary history and what maybe the past can tell us about current practices, and even maybe where we can go in the future.

But my experience still is just that there’s a lot of people who are unfamiliar with African Americans in this way. They’re still coming to it fresh. And I feel like I’m still in a way just trying to teach people.

If more people were part of cultural conversations, in this case about African foodways translating into African American foodways in the United States, do you think that would help prime those conversations at the table?

Definitely. Here’s the trap in all of this: A lot of people are just not careful, and they kind of make stuff up. I think that that could really be damaging, because I think we all should be endeavoring to find the truth, and I think seeking the truth about food and its backstory may get to the point where we start eliminating long-held beliefs that benefit our culture.

Every once in a while, you’ll see someone try to say definitively that X food came from Y place, because of course, X food is delicious and so that Y culture wants to claim it, right: “Yeah, we’re the ones who did this first.” But a lot of this food history is just not documented; we can make educated guesses, but to show a clear provenance of something is usually very difficult to do.

I’ll take the example of fried chicken. It’s one thing to say fried chicken is from West Africa, my research indicates that it’s probably from Western Europe, probably Scotland. But you know, nobody knows for sure. But one thing we can do is look at how so many different cultures around the world plug into this tradition and how they make this dish. What we can learn about that? What does that tell us about cultures? How can that bring us together?

I would love to learn a bit about your research process. I don’t know if you are, quote-un-quote, allowed to share your process for the book you’re currently working on? [Adrian laughs.] I don’t know! I don’t know if there’s secrecy or something! [Adrian and Sarah laugh.] Is there a general research process that you have?

I think the first thing that anybody has to do is see what’s already out there. You have to look at books, go online, and see if anybody’s already written on that subject, then see if it’s persuasive to you or doesn’t ring true.

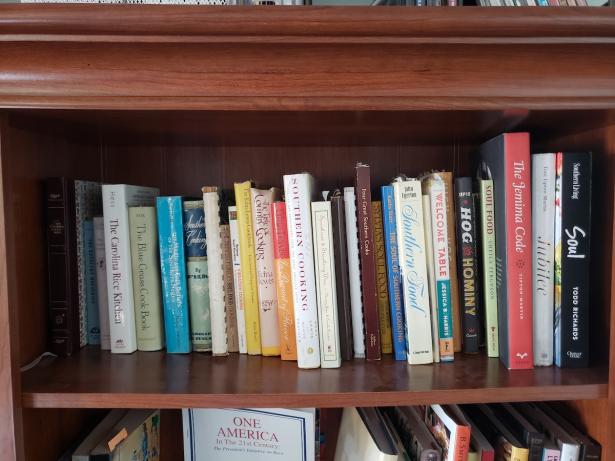

My speciality has been writing about stuff that’s never really been covered before, or from angle that’s never been touched before. There was certainly the work of Dr. Jessica B. Harris, but no one had ever done a scholarly treatment of soul food. My second book, on African American presidential chefs—no one has ever written about them in a comprehensive way. And my book on African American barbecue that’s forthcoming [Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue]—no one’s ever written a book just on the history of African American barbecue. There have been historical treatments of barbecue that have mentioned African Americans quite a bit, but nobody’s really said, “From an African American point of view, this is how the story plays out.”

The boon for my research has always been digitized newspapers, because newspapers were intended to capture the daily life of a community. The next thing I do is look for any oral history, hopefully in the time period that I’m looking at. But I love just talking to people about what they think about food, and when you have those conversations, you see where some long-held stuff springs up and endures.

Take chitlins: One of the enduring perceptions of chitlins is “Oh, it’s the master’s trash, it’s the food that white people don’t want.” Pig intestines were things that were going to spoil very quickly, so you had to eat them right away. Often as a reward for all the hard work of hog killing, the enslaver would give the enslaved workforce chitlins to eat. That created the notion that this is the stuff the master didn’t want.

But when you look at the historical record, you find that white people were eating plenty of chitlins. I shared this during a radio interview a couple weeks ago, and the host was fighting with me. I was like, “I found this and this,” and he just didn’t want to believe me.

The last part [of research], which I love to do, is fieldwork. You have to go to these restaurants, if you’re talking about restaurant culture; if you’re talking about home cooks, you have to go see what people are doing. That part is really hard, because I’ve never ever had enough resources to adequately do it. I’ve always felt bad. I felt like my books were informed, but I felt like they could always be a little more informed, but I just never got the resources. I’ve applied to scholarships and stuff to buttress the advance I got from the publisher, but I’ve never received any kind of grant for that work.

How has COVID affected your work on Black Smoke right now? Were you able to get in field work before COVID?

I had made maybe 10 trips, but due to COVID, there were some trips I just didn’t get to make. I had hoped to go back to Los Angeles and San Francisco, and I wanted to go to Kansas City and St. Louis—St. Louis moreso, because I’d eaten in Kansas City within the last couple of years.

You mentioned as you go back through research and through documents, you find evidence that contradicts some long held beliefs or myths. Were there any times that things you learned rewrote a history for you?

Basically, all the negative things I’d heard about soul food. ‘Soul food is the master’s leftovers, soul food is the food the master didn’t want, soul food is inherently unhealthy.’ Think about what the nutritionists are telling us to eat: more dark leafy greens, more sweet potatoes, more fish, okra, hibiscus. All these things are the building blocks of soul food.

Soul food is really celebration food. Most of the stuff we think about, like barbecue, the glorious cakes and pies, fried chicken, chitlins—people would eat that every once in a while, for special occasions. You look at any culture, and if you eat those special occasions foods on the regular, it’s not gonna be good for your body.

Only 40 percent of slavery were those big plantations, like with Gone with the Wind, where you had two teams of cooks: one for the big house, one for the people working the fields. So for 60 percent of the enslaved people, they were pretty much eating the same food as their slavers, because they were either in an urban slavery context or they were in a small farm, and in those contexts, it did not make sense to have two separate teams of cooks making two different types of food.

That was eye-opening: to see how soul food spread, to see the rich diversity of soul food. And then to find out that even in the South, a lot of people don’t even use the term soul food; they just call it home cooking or country cooking. All of those things were a revelation.

My only two things that I had really known about soul food, other than that it was my tradition, was, “We took something that was horrible and made it delicious,” and “Don’t eat too much of it, because it’ll kill you.” My book was really to test what was fact and fiction about those two ideologies.

I think that the more you put food into frame with the context of geography, with the context of history and politics, it illuminates so much more.

On a totally different note, I’m curious: What was the process for becoming a certified barbecue judge?

I found out about a cooking competition for the Kansas City barbecue society, and at that point in time, they were looking for judges. I knew I was going to write about soul food, and so many soul food joints have a barbecue menu option, so I thought I would learn a little bit more about barbecue.

You come into this room, you sit down, and they go through the categories, then tell you how to score each category. They bring out samples and have you judge them, to make sure that you score correctly. After that, you stand up and take a barbecue oath, which is a sacred thing. I’m not going to repeat it right now. [Sarah laughs.]

I respect the sacral nature.

Then you get your badge in the mail, and at that point you can go judge any contest within that sanctioning body.

What are those hallmarks of barbecue that beat out the rest of the competition?

The judging criteria is texture, taste, and appearance. You want to have something that’s really tender, you want something that’s very flavorful, and you want something that looks gorgeous. That’s why competition barbecue is really not a reflection of reality, because it’s perfectly manicured barbecue. I mean, do you know people who have syringes in their kitchen so they inject stuff into the food?

We had a very tiny syringe of medication for the cat. I think we still have the syringe, but it’s not for cooking or baking. I kind of want one, though. It feels really official.

My last question is about your slogan: “Dropping Knowledge Like Hot Biscuits.”® [Adrian laughs.] It’s brilliant. How did you come up with that slogan, and what led you to trademark it?

I’m very proud of that one. I had all these inspirations. I came up with “soul food scholar,” and I was proud of that, but then I thought I needed to have more of a hook, because I knew that the scholar part could turn some people off, that it was kind of boring.

One day, I was thinking about different songs, and I thought about Snoop Dogg’s “Drop It Like It’s Hot.” [Sarah bursts out laughing] I was like, “Well that’s what I’m trying to do.” And I thought, “What’s hot in soul food? Biscuits.”

There was one more step. In law school, there was this guy who I was kind of giving a hard time, and he said, “Let me drop knowledge on you like bombs.” I thought that was hilarious and that always stuck me. So I was thinking about that phrase, and then I thought about Snoop Dogg [Sarah laughs] and then I thought, “Okay, biscuits.” That’s how it came together.

I started telling people that. I put it on my business card, and so many people reacted to it. There are people who have my business card on their fridge, just because they love it so much. Then I said, “Okay, I need to trademark this.”

Sarah Cooke is a freelance writer whose work, including her weekly newsletter Deliciously Intense, Surprisingly Balanced, explores the intersection of food, culture, and power. She lives in Washington, D.C.

Spread the word