As a staple of airport newsstands and dads’ birthday gifts, thrillers are wildly popular. With $728.2 million in American book sales, crime and mystery books are second only to romance and erotica, and, when lumped in with mysteries, “50 percent of respondents in a recent [Book Ad Report] survey stated that mystery/thriller books were their favorite genre of e-books.” Thriller authors tend to be prolific, with many writing a book a year, and cultivate loyal audiences that will read most, if not all, their books, exposing readers to a frame of thinking over and over. These novels tend toward conservatism but are not exclusively reactionary; nonetheless, popular conservative hosts like Glenn Beck—who has dabbled in writing thrillers himself—and Hugh Hewitt have used their platforms to heavily promote reactionary conservative thrillers that reinforce their own worldview. Thrillers are usually fun adventure romps but, read uncritically, they also have the potential to influence how readers view real-life foreign policy and national security issues.

One of the architects of the thriller as we know it today was Ian Fleming, whose James Bond novels have inspired one of the most famous and enduring film series of all time. In the Bond movies, the handsome British spy is generally a debonair man of action who uncovers a megalomaniacal villain’s plot, leading him on an adventure complete with travels to exotic locales, hypermodern gadgets supplied to him by irascible inventor Q, and encounters with two or three women—at least one of whom must be killed. The novels themselves tend to be less formulaic; Fleming, for instance, often exposes Bond’s vulnerability and fleshes out his relationships with women in greater detail. And in the early stories, Bond’s adversary is generally SMERSH, the USSR’s real-life counter-intelligence organization, rather than imaginary or non-state actors. The books were wildly popular: in fact, John F. Kennedy even cited From Russia With Love as one of his ten favorite books. Fleming passed away in 1964 but the Bond franchise lives on, in novels written by a slew of (male) authors who have tried to carry on the Bond legacy. Still, none have matched the success of the Fleming originals, which have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide.

Like many spy novelists, Fleming was a former intelligence officer himself. As Ben Macintyre details in his Fleming biography, For Your Eyes Only, many British intelligence officers of that era were selected from the ranks of the upper class. Born to a wealthy family and the son of a member of Parliament, Fleming was recruited shortly before the advent of World War II to the role of personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence. In that position, Fleming wrote memos devising possible intelligence operations. Later in his career, he would direct a group of British Commandos that operated near the front lines to steal documents. Bond was, in Fleming’s words, “a compound of all the secret agents and commando types I met during the war,” though some character elements—from Bond’s preferred brand of cigarette to his penchant for scrambled eggs—were more clearly autobiographical.

As author of Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born—Ian Fleming’s Jamaica, Matthew Parker, has detailed, the Bond series was Fleming’s attempt to grapple with the post-war dissolution of the British empire. British intelligence agencies like the Secret Intelligence Service were losing prestige, and the United States had overtaken Britain as the preeminent global superpower. The result of this was a fantastical man of action who could roam the world freely, advancing British interests, something Fleming largely frames as positive and stabilizing for the world, while ignoring the crimes and bloodshed perpetuated by the British Crown.

And so, while the Bond novels are more nuanced than the movies in some ways, they are even more reactionary, steeped in an ideology of militarism and imperialism. They are also famously misogynistic and quite racist. Even for the 1950s and 1960s, Fleming’s writing was virulently racist, sexist, and homophobic, much of which was toned down in the movie adaptations. In Dr. No, the Colonial Secretary of Jamaica says:

“The Jamaican is a kindly lazy man with the virtues and vices of a child. He lives on a very rich island, but he doesn’t get rich from it. He doesn’t know how to and he’s too lazy. The British come and go and take the easy pickings… It’s the Portuguese Jews who make the most. … Then come the Syrians, very rich too, but not such good businessmen… Then there are the Indians with their usual flashy trade in soft goods and the like. They’re not much of a lot. Finally there are the Chinese, solid, compact, discreet—the most powerful clique in Jamaica…They keep to themselves and keep their strain pure… Not that they don’t take the black girls when they want them. You can see the result all over Kingston—Chigroes—Chinese Negroes and Negresses. The Chigroes are a tough, forgotten race. They look down on the Negroes and the Chinese look down on them. One day they may become a nuisance. They’ve got some of the intelligence of the Chinese and most of the vices of the black man.”

It doesn’t seem that Fleming (who frequently wintered in Jamaica) means to indicate to the reader that the Colonial Secretary is a racist, out-of-touch imperialistic scourge; rather, the Secretary’s racist caricatures are largely treated in the world of the novel as accurate depictions. At the conclusion of one particular chapter, the ominousness of the cliffhanger hangs on the revelation that a certain character is Chinese. The British domination of Jamaica is treated as both a historical given and a morally correct condition; the sun shouldn’t set on the British empire, the books would seem to claim.

"Crime @ the Library" by nataliesap is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The popularity of Bond has influenced a generation of thriller authors, many of whom have happily infused their books with the same reactionary, imperialist ideology that drives the Bond universe. Tom Clancy, Fleming’s clearest American counterpart, wrote 20 novels in his lifetime, 17 of which became New York Times best sellers. His thrillers have inspired blockbuster movies like The Hunt for Red October, video games such as Tom Clancy’s Ghost Recon, and most recently the Jack Ryan television series produced by Amazon. At the time of Clancy’s death in 2013, more than 100 million copies of his novels were in print.

Clancy wrote his own Bond-like character: Jack Ryan, a heroic CIA officer. The Jack Ryan novels are somewhat different in approach: they’re longer, less rooted to one protagonist, and focus more on institutional operations than the heroics of any singular figure. And Ryan—especially compared to the philandering James Bond—is a sober family man. But there are also key similarities with the Fleming works, particularly when it comes to ideology. Where Fleming dreams, nostalgically, of an empire that never ended, Clancy often provides neoconservative wish-fulfillment fantasies in which the already dominant America gains even more power over its rivals.

In Clancy’s 1986 novel Red Storm Rising, for instance, Azerbaijani militants destroy an oil production refinery in the USSR. The Soviets respond with a plan to invade the Persian Gulf, but not before they attack Western Europe. The Soviets’ goal is nothing less than neutralizing the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the mutual defense pact between the United States and Western European countries, founded after World War II to counter the USSR’s growing power. In Clancy’s book, NATO proves too strong for the USSR, and when hawkish members of the Politburo consider nuclear retaliation, a Soviet military leader stages a coup. NATO’s military superiority is asserted over the USSR and the status quo is restored. Every neoconservative would have dreamed of this outcome at the time: a scenario in which the USSR is the aggressor, giving the United States and its Western European allies the moral high ground while resoundingly proving their military superiority, and showing that NATO could successfully contain the USSR, as it was designed to do.

In another extreme fantasy, The Bear and the Dragon (set after the fall of the USSR), U.S. intelligence learns that China plans to invade Russia and take control of newly-discovered oil and gold resources to compensate for an economic downturn. To deter China from carrying out this plan, now-President Jack Ryan (yes, he gets to be president, meanwhile poor Bond never gets to be prime minister) convinces NATO to let Russia in, with the hope that China will back off in fear of retaliation from NATO.

Russia in NATO may seem like a wild idea, since again, in reality, the main purpose of NATO’s was to serve as a counterbalance to the USSR. When the USSR dissolved in 1991, the continued relevance of NATO was up for debate. While the international body stayed intact, the U.S. made tremendous efforts to get Russia to embrace neoliberalism and to prevent Communists from taking power in subsequent elections. In the 1996 election, for example, Boris Yeltsin had an approval rating of 6 percent and a decimated economy on his hands. Bill Clinton lobbied the International Monetary Fund to give Yeltsin a $10 billion loan, providing Yeltsin a major boost in the election, which he went on to win (there were, however, serious allegations of outright election fraud). Under Clinton’s direction, NATO continued to expand into Eastern Europe, with Yeltsin’s somewhat confused approval. In The Bear and the Dragon, Clancy imagines a Russia that goes beyond embracing America’s economic model to become an American military ally. More than that, Clancy frames NATO as a body of the utmost importance. The idea that NATO could someday include Russia itself would’ve exceeded even Clinton’s wildest fantasies.

The dissolution of the USSR also caused the American public and politicians alike to question whether such a massive military budget was necessary. In Clancy’s written world, the answer is a resounding yes. At the climax of The Bear and the Dragon, the fetishization of American military might and hardware that pervades so much of the Clancy canon is on full display. Defeated by NATO forces, Beijing launches nuclear missiles against America. But the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System, a real-life expensive military project designed to shoot down incoming missiles, saves America at the last minute. What brings the enemy down for good, however, is American ingenuity. Towards the end of the book, U.S. intelligence broadcasts CNN reports about the invasion over a CIA website to counteract Chinese Communist Party propaganda. This in turn inspires a revolution reminiscent of the real-life Tiananmen Square protests. The Chinese government topples, and here begins China’s transition to a capitalism-friendly democracy (as if the real China hasn’t been quite capitalism-friendly for a while).

Clancy sells an America that always behaves nobly, and characters whose moral goodness hinges on their patriotism. Meanwhile, her rivals, the USSR and China, are always the aggressors. This is ahistorical to say the least; there are far too many examples of American aggression in the name of anti-Communism to list in this article, but some of the most egregious examples include the Korean war, during which American escalation killed 3 million civilians, or 20 percent of the country’s population. Or consider the 1953 Iranian coup, in which the CIA overthrew Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister to restore authoritarian rule by the Shah, all to stop the nationalization of Iranian oil. Then there’s American involvement in the 1973 coup in Chile; there, the Nixon Administration worked to destabilize the Chilean government through economic warfare and election interference, ushering in the brutal rule of Augusto Pinochet. But the truth of these events doesn’t exist in Clancy’s world, where the American empire can do no wrong.

While the Bond scenarios are more obviously outlandish (from a voodoo cult leader smuggling pirate treasure to fund Soviet spy operations to an allergy clinic brainwashing young women into destroying British agriculture through biological warfare), Clancy’s have been praised for their accuracy in portraying the workings of the military. President Reagan famously recommended Red Storm Rising to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to understand Soviet intentions and strategy in preparation for nuclear-disarmament talks. “They’re not just novels,” former Vice President Dan Quayle once said. “They’re read as the real thing.” This reception, and the use of military-industrial complex jargon throughout the books, has lent them a veneer of authenticity that may let some readers believe they are being educated as well as entertained. This, I suspect, primes readers to accept the ideology underlying their rabidly conservative premises and expectations. Clancy’s novels may be entertaining, but they’re quite clearly propaganda.

"Robyn's bookshelf" by OU Platform is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

When the Cold War ended, America’s conservative thriller authors searched for a new adversary to loom over their plotlines and to justify militarism. The terrorist attacks on 9/11 provided just that. The thriller writer most emblematic of War on Terror conservatism is probably the late Vince Flynn, author of the Mitch Rapp adventures (monosyllabic hero names aren’t a genre requirement, exactly, but they convey a certain masculine abruptnes). Rapp is a counterterrorism operative who routinely works in the Middle East, from where he heroically protects the United States from terrorist attacks. Despite the fact that torture tactics such as waterboarding are an illegal violation of human rights, and they have failed to prevent real terrorist attacks while radicalizing people against America, Rapp tends to choke people with his bare hands in exchange for information. As in the Bond and Ryan novels, the only good people among the native population where Rapp finds himself are those allied with America. While President George W. Bush was declaring, “you’re either with us, or with the terrorists,” Flynn was happy to paint anyone publicly skeptical of the War on Terror as a traitor. His thriller The Last Man contains a subplot involving a U.S. Senator critical of American policy in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, Rapp is focused on investigating the kidnapping of the head of CIA clandestine operations in Afghanistan. In a plot twist, Flynn reveals that the Senator had been in contact with the Pakistani general behind the kidnapping plot.

In reality, most of our democratically elected leaders enthusiastically supported and voted for the war in Afghanistan. The sole member of either chamber of Congress to oppose the bill authorizing military force in Afghanistan was Congresswoman Barbara Lee. For this vote, Lee was castigated and sent death threats. Her courage and conviction in the face of such opposition is a far cry from the Senator depicted as craven and traitorous in The Last Man. While the Iraq war wasn’t nearly as unanimously supported, it was still championed by prominent members of the Democratic Party, from the current President-Elect Joe Biden to John Kerry, the 2004 Democratic Presidential candidate who ran against Bush.

Curiously, by the publication of The Last Man in 2013, the Iraq war and broader War on Terror, which, by that point, entailed bombing campaigns in Afghanistan and six other Middle Eastern countries, were all widely regarded as a mistake. But that didn’t stop Flynn from treating skeptics of the War on Terror with just as much disdain as Barbara Lee’s critics did at the time of her lone vote a few days after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Following the big reveal, Rapp confronts the Senator with evidence of the uncovered treason and blackmails him into becoming a CIA lapdog. As a parting shot, he tells the scheming politician, “There is a third option… I sneak into your house in the middle of the night and snap your neck.” The message is unambiguous. Anyone critical of the War on Terror is a traitor, or as good as one, and only the noble deep state can keep our corrupt representatives in line.

Thrillers, more so than any other genre, can be a powerful tool to spread political messages. This is in part because they’re wildly popular and also, because unlike fantasy or science fiction—much of which is set in a world so dissimilar to ours that it must rely on metaphor or allegory to make political commentary—thrillers tend to unfurl in recognizable surroundings. The starting points of reference require less effort from the reader seeking to decipher the politics that make some characters heroes and others villains. A reader that lacks a grasp of history and geopolitics might be tempted to adopt the politics presented as “good” as their own. This is especially a concern when the novels are precise and accurate in their portrayal of military hardware and procedure—features that readers might interpret as a sign of expertise in military affairs, leading them to conclude that what Clancy and other conservative thrillers categorize as “good” and “evil” is just as trustworthy.

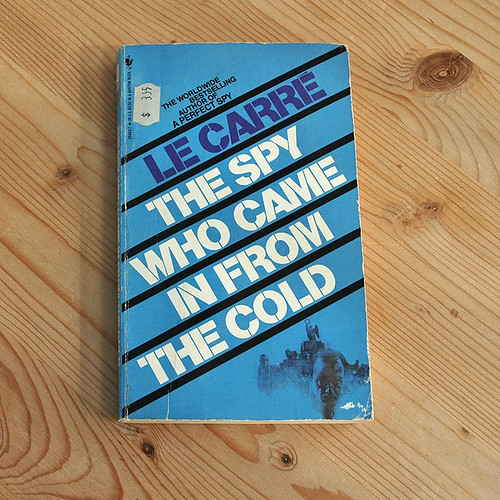

"The spy who came in from the cold, J. le Carré" by Peter576. is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Now, there have long been liberal alternatives to conservative thrillers (le Carré is one good example), but authors who directly and specifically challenge American militarism from a leftist perspective are in shorter supply. The best example of such an author may be Barry Eisler, who made headlines after Elizabeth Warren listed him as one of her favorite authors during her Presidential campaign. Eisler doesn’t describe himself as a leftist, preferring to eschew labels, but his books and his blog reveal a commitment against civil liberty violations, warrantless surveillance, torture, and American drone policy, all of which he has addressed in his novels.

In his standalone novel The God’s Eye View, Eisler builds on the Snowden revelations that the National Security Agency ran an unconstitutional surveillance program for years. In The God’s Eye View, an NSA employee discovers that one of her coworkers was murdered because he intended to reveal their employer’s activities and capabilities. Departing from Bond, Ryan, and Rapp, heroine Evelyn Gallagher is a woman (with a multi-syllabic name) who works for the NSA to make ends meet, rather than out of a deep-seated commitment to its mission and belief that spying is necessary to keep Americans safe. Once she suspects wrongdoing, Gallagher’s instinct isn’t to defend the state; on the contrary, she quickly seeks to reveal the truth despite the danger involved. At the time The God’s Eye View was published, whistleblowers who leaked information about questionable national security or military activities were still being ruthlessly targeted by the Obama administration. For giving secret military documents to Wikileaks in 2010, the former U.S. soldier Chelsea Manning was called a traitor who threatened national security and has been detained in conditions deemed torturous by the United Nations. It’s a considerable change from both conservative thrillers and mainstream news headlines to portray a whistleblower as the hero.

But Eisler’s most innovative protagonist may be Ben Treven, the elite soldier at the center of the novel Fault Line. At first glance, Treven is similar to Rapp, Ryan, and other conservative protagonists in the genre. He’s committed to American militarism and distrusts foreigners and immigrants from presumed rivals such as Iran. Treven finds American critics of U.S. foreign policy and militarism, especially civilians, weak and naive. But while Rapp and Ryan truly believe the American military behaves with the noblest of intentions, and in the best interests of both Americans and the people they occupy or bomb, Treven is less charitable. As Eisler writes in the early pages of, Fault Line:

thought about hate. America was hated overseas, true, but was pretty well understood, too … Americans thought of themselves as a benevolent, peace-loving people. But benevolent, peace-loving peoples don’t cross oceans to new continents, exterminate the natives, expel the other foreign powers, conquer sovereign territory, win world wars, and less than two centuries after their birth stand astride the planet … It was the combination of the gentle self-image and the brutal truth that made Americans so dangerous. Because if you aggressed against such a people, who could see themselves only as innocent… they would react not just with anger, but with Old Testament-style moral wrath. Anyone depraved enough to attack such angels forfeited claims to adjudication, proportionality, even elemental mercy itself. Yeah, foreigners hated that American hypocrisy. That was okay, as long as they also feared it.

Treven may not share Rapp’s naive belief in the nobility of America’s intentions, but he too starts out fully committed to America’s militarism. In a Clancy or Flynn novel, Treven would be the faultless hero—his worldview and righteousness unchallenged—with the villains consisting of foreigners or critics of American militarism. But under Eisler’s pen, Treven is faced with the inadequacies of his worldview and the true horrors of which the American military-industrial complex and intelligence apparatus is capable, which are worse than he had imagined. Many of the horrors he faces are based on real events. The second novel of the Treven series, for example, prominently features the 92 tapes allegedly destroyed by the CIA, which contained evidence of Americans torturing prisoners. Treven changes as a result of facing villainous forces within the American military-industrial complex, and his prejudices are interrogated as he comes to know and respect an Iranian-American lawyer. Just as The God’s Eye View upends the tropes in the older generation of thrillers by reframing those trying to warn the public of their own government’s misdeeds as heroes, Fault Line allows the hero to become enlightened upon exposure to information that challenges his presuppositions. Liberal thriller authors (such as Robert Ludlum, famous for The Bourne Identity and its sequels) often set their heroes against people within the American intelligence apparatus, but these villains are usually portrayed as a few bad apples with outlandish schemes, and the heroes safeguard America’s noble institutions by defeating them. But Eisler goes further by portraying the institutions themselves as flawed, and does so in a literary way by barely exaggerating what these institutions are already doing. As such, he provides a stronger counter-narrative to conservative thrillers than the liberal version.

The success of Eisler’s novels shows that there is an appetite for thrillers critical of American militarism and imperialism, plots for which America’s foreign policy provides ample material. Just as conservative thrillers exploded in popularity following the success of the James Bond novels, it’s possible that under the right conditions, and with the right promotion, thrillers with a leftist lens would have the potential to become just as popular and influential over the coming decades. In the best of real-life plot developments, they might even influence readers and politicians to seriously question America’s foreign policy. Understanding this phenomenon presents an opportunity for the left, not only to pay attention to the most popular conservative thrillers in order to challenge their political messages, but also to buoy thriller authors who offer counternarratives to the standard neoconservative normplot.

For conservative thrillers to sell their ideology and defend American militarism and aggression, they need to present a simplistic and distorted view of the world. The result can be an entertaining story, as long as you don’t ask too many questions about real-world events. But any thriller rooted in a more complete, accurate view of the world will invariably be forced to grapple with the damage and violence caused by the American military-industrial complex and other issues raised by leftists. The result can be stories that are far more complex, thought-provoking, and truthful than any conservative thriller while remaining just as entertaining, if not more so. In the true history of American intelligence operations, there are more than enough twists, turns, unlikely heroes, and powerful villains to put James Bond and Jack Ryan to shame, without apologizing for any empires along the way.

SEE PRAVEEN TUMMALAPALLI’S OWN INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR BARRY EISLER BELOW!

Watch here

Spread the word