Fifty Years Later, Pentagon Papers Still Speak Loudly About War and Government Untruths

In the middle of a controversial war, in the middle of generational conflict, in the middle of a contentious presidential administration, a single finger depressing a starter button in a manufacturing plant in Manhattan 50 years ago rocked the nation.

As the last strains of dance music from a 15-piece orchestra faded at the White House wedding of Richard Nixon’s daughter Tricia, the editors of The New York Times were bracing themselves 225 miles away for an assault from the bride’s father. The presses that the starter button set in motion themselves set in motion one of the great political controversies and legal battles of the 20th century.

The newspapers rolling off those presses were carrying excerpts from a study that would be known in history — history that the study, its interpretations, and misinterpretations would spawn — as the Pentagon Papers.

Like the “Odyssey” and “Paradise Lost,” the Pentagon Papers would be more cited than actually read. Indeed, no academic monograph with the possible exception of Charles Darwin’s 1859 “Origin of Species” would have the impact of this work of 36 scholars toiling down the hall from the Pentagon office of Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara. They eventually produced 2.5 million words that filled 47 volumes weighing 60 pounds and gave a bracing account of American involvement in Vietnam from the end of World War II to 1967.

More important than its size was its scathing honesty. It was a minutely documented account of how unimaginably and disastrously misguided that involvement was: begun on unfounded Cold War convictions about the importance of Vietnam’s security to our own, pursued with escalating brutality but never a coherent strategy, and cynically perpetuated for more than a decade — and more than 38,000 lost American lives — after top advisers to President Lyndon Johnson told him repeatedly they deemed it unwinnable.

It was, that is, a vast catalog of inconvenient truths — truths that begged the great questions that lingered, loud and haunting, into the Nixon years: Why are we still in Vietnam? Why are young men still being sent to die there?

No president of the war era was ready to answer them, for fear of “losing” the war and losing face. And so the report’s existence had to be kept secret, and was, until the day those presses rolled — at the Times and, soon after, at The Washington Post and The Boston Globe.

A half-century later, the publication of the Pentagon Papers has both less and greater significance than it did on June 13, 1971. And yet their release speaks as loudly to our time as it did in the long-ago month in which the first Hard Rock Cafe was opened and when Carole King performed for the first time.

The American wars still to come would have their own bodyguards of lies.

Daniel Ellsberg was surrounded by reporters at the Federal Building in Boston on June 28, 1971. Bettmann/Bettmann Archive

“The Pentagon Papers foreshadowed Iraq and Afghanistan in that they showed presidents’ ability to keep secrets — the exact thing we saw in Vietnam,” Daniel Ellsberg, the Defense Department scholar who released the papers, said in an interview for this retrospective. “There are no big Afghanistan Papers and no Iraq Papers but they would show the same kind of thing: Progress in those wars was a lie, and there was no progress that was going to happen, and the leaders told themselves that but didn’t tell it to the public.”

The release of the Pentagon Papers — at that point the largest-ever disclosure of classified documents — didn’t bring American involvement in Vietnam to a close; the last Americans were not evacuated from Saigon for nearly five more years. The legal battles that followed, as the Nixon Justice Department asked the Supreme Court to halt the publication and was firmly rebuffed, did not leave the American press unfettered; reporters feared imprisonment for leaks of national security information as recently as the Barack Obama years, and Donald Trump waged psychological war against the press.

But there is no minimizing the drama that began to unfold when Ellsberg began seeking an outlet for the documents and found one in Times reporter Neil Sheehan. Sheehan immediately launched a frantic but furtive effort to copy them — against the wishes and without the knowledge, we now know, of Ellsberg, who was looking for another impactful outlet, preferably on Capitol Hill. That drama gave rise to the popular 2017 film “The Post,” about publisher Katharine Graham’s decision for The Washington Post to follow the Times in publishing the papers, handed to her newspaper by Ellsberg in two cardboard boxes.

“The story was worthy of an entire film,” director and producer Steven Spielberg said in a recent telephone conversation. “I never bought the idea that the Pentagon Papers were a threat to national security. We — Tom Hanks, Meryl Streep — were all drawn to this. The chief executive in the Oval Office — Richard Nixon — was basically trying to shut down the free press. It had ironic parallels to the threats we have all just lived.”

Communist domination, by whatever means, of all Southeast Asia would seriously endanger in the short term, and critically endanger in the long term, United States security interests

— 1952 National Security Council Policy Study on Southeast Asia, printed in the Pentagon Papers

In his introduction to a book edition that grew out of the publication of the Pentagon Papers, Sheehan said that to “read the Pentagon Papers in their vast detail is to step through the looking glass into a new and different world.”

And those in that world with eyes to see were stunned.

John F. Kerry was back from Southeast Asia, leading the Vietnam Veterans against the War. Less than two months earlier he posed his haunting question to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”

John Kerry, 27, testified about the war in Vietnam before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in on April 22, 1971. HENRY GRIFFIN

“The papers were a stunning confirmation of my remarks, and it had enormous impact on me,” Kerry recalled this spring. “I remember being furious at the fact that our government was officially lying. It was a double lie — a lie about the realities of the war and a lie about whether there was a strategy. It wasn’t just about dying for a mistake. It was about dying for a lie.’'

The impact was powerful, too, in shaping America’s sense of its place in the world — and of the honor, or want of it, of its political leaders.

“Publication of the papers strengthened public and congressional opposition to continued American involvement in Vietnam,’' George C. Herring, a University of Kentucky expert on the Vietnam War, wrote in the Introduction to a 1993 edition of the papers. “Few people read them, to be sure. Still, the revelations in them — or, perhaps more accurately, the reports of the revelations — challenged the myth of America as a reluctant participant in the war, added to an already large credibility gap between public and government, and gave legitimacy to some of the key arguments of the antiwar opposition.”

Nearly three decades since the Herring interpretation, scholars have come to believe the Pentagon Papers had little influence on the course of the war, though their release stirred fears in Nixon and Henry Kissinger of further disclosures that could be damaging to them. “It made them worry . . . that the floodgates would be open and their own papers could leak,” said Fredrik Logevall, the Harvard historian and author of “Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America’s Vietnam,” which won the Pulitzer Prize.

Nor do contemporary scholars believe the papers substantially turned public opinion against the war; the trends in public opinion already had turned. “But the papers provided confirmation for a lot of things that the critics of the war had been saying,” said Edward Miller, a Dartmouth College historian and adviser on Ken Burns’s television history of the war, which aired on PBS in 2017. “The ‘credibility gap’ had been talked about for years before 1971, but the evidence in the papers demonstrated it in spades.”

That evidence reinforced not only the viewpoints of antiwar protesters but also the perceptions of veterans of the war.

“The papers showed me how a lot of the people involved in policy-making actually knew they were building on a house of cards,” said former senator Bob Kerrey of Nebraska, a onetime Navy SEAL who lost part of his right leg in combat two years before the release of the documents.

The South Vietnamese are losing the war to the Viet Cong. . . . No one has demonstrated that a white ground force of whatever size can win a guerrilla war — which is at the same time a civil war between Asians — in jungle terrain in the midst of a population that refuses cooperation to the white forces (and the South Vietnamese) and thus provides a great intelligence advantage to the other side.

— Memo to Lyndon Johnson from Undersecretary of State George W. Ball, July 1, 1965

Whatever the impact in politics, the Pentagon Papers had enormous influence in military circles.

“The papers revealed the degree to which we went to war without a strategy,” said Trump-era national security adviser H.R. McMaster, who served in the Gulf War, the Iraq War, and Afghanistan and who wrote his PhD thesis on the Vietnam War. “Americans were already loosing faith in the war and this showed gross incompetence by our leaders.”

President Richaed Nixon met with Ellsworth Bunker, the US ambassador to South Vietnam, and Henry Kissinger in June 1971. Associated Press

Ellsberg didn’t set out to illuminate the incompetence of leaders of the past; his real goal was to change the present. He wanted the Pentagon Papers to nudge Nixon away from his Vietnamization project, which was intended to shift the burden of the fighting in Vietnam to the ground forces of South Vietnam.

“I hoped for congressional hearings that would lead into the question of where Nixon was going, what his plans and aims were,” he said in the interview. “I was worried he would keep the war going and even escalate it. My perspective was different from most people’s. They thought Nixon was getting out of the war as best as he could and that it was for all practical purposes over. Had I believed that, I would never have copied the Pentagon Papers and put myself in danger of going to prison. I was convinced Nixon had aims that would not be achieved in his first term and that the war would get bigger.”

At the heart of the Ellsberg calculation — and commonly forgotten today — was that the history the papers documented ended before Nixon was inaugurated and that the principal focus was on the Kennedy and Johnson years. He hoped that a Republican partisan like Nixon would seize on that, blame the Democrats for the debacle, and avoid the errors of two men he reviled.

H.R. Haldeman, the pugilistic chief of staff of the Nixon White House, tried to calm the president even as he issued a veiled warning to him.

“To the ordinary guy, all this is a bunch of gobbledygook,” he told Nixon a day after the Times began publishing. “But out of the gobbledygook comes a very clear thing: You can’t trust the government, you can’t believe what they say, and you can’t rely on their judgments. And the implicit infallibility of presidents, which has been an accepted thing in America, is badly hurt by this, because it shows that people do things the president wants to do even though it’s wrong, and the president can be wrong.”

That is the principal lesson of the Pentagon Papers that Nixon — 52 weeks and three days from the Watergate break-in — failed to learn.

he odds are about even that, even with the recommended deployments, we will be faced in early 1967 with a military standoff at a much higher level, with pacification still stalled, and with any prospect of military success marred by the chances of an active Chinese intervention.

— Memo to President Johnson from Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara, Dec. 7, 1965

The Pentagon Papers were not written with the remotest suggestion that they would appear in the press, nor with the notion that they would prompt perhaps the most important journalism question in modern American history.

While hosting Defense Secretary Robert McNamara at the LBJ Ranch in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson reacted to news of new problems in Vietnam.Historical/Corbis via Getty Images

They were assembled to respond to a classic request from McNamara, who surrounded himself with a group of theorists and thinkers from the RAND Corporation known as the “Whiz Kids.” He wanted classified answers to about 100 topics that Leslie H. Gelb, who directed the project and who ironically ended up at The New York Times two years later, called “dirty questions.”

But the papers were a time bomb whose ticking Ellsberg, another RAND thinker, could not expel from his mind.

His first inclination was to get them exposed in Congress. He met disappointment and resistance. The ultimate destiny of the Pentagon Papers — their appearance in 19 newspapers — began innocently enough in the Joyce Chen Small Eating Place between Harvard and MIT in Central Square, Cambridge. There, the MIT linguist and social critic Noam Chomsky suggested to the Globe’s Thomas N. Oliphant that perhaps he ought to track down someone named Daniel Ellsberg.

Oliphant did, and after two lunches with Ellsberg wrote a story on March 7, 1971, about a “secret Indochina report.” That set in motion panic in the White House, an FBI manhunt to find the leaker and the cache of documents, and a journalistic race to get the Pentagon Papers into print.

Sheehan, who had covered the war from 1962 to 1966, was quickly in touch with Ellsberg, beginning a tortuous series of negotiations marked by trust (the shared conviction that these documents were significant) and deception (Sheehan and his wife, the New Yorker writer Susan Sheehan, quietly photocopied the documents, portions of which Sheehan had quietly acquired separately).

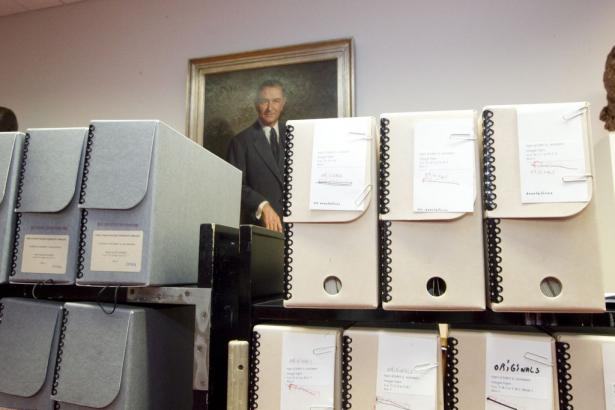

A.M. Rosenthal congratulated Hedrick Smith after publication of the Pentagon Papers in The New York Times in June 1971. Neil Sheehan is second from right. RENATO PEREZ/NYT

Before long the documents were secreted along with a Times team in the New York Hilton.

As the excerpts from the papers started rolling off the Times presses and as the Justice Department was seeking an injunction, Ellsberg offered the papers to The Washington Post, which began printing them as well. Third came the Globe, in part because Ellsberg had admired the newspaper’s antiwar editorial and stance and had warmed to editor Tom Winship when they encountered each other on a Caribbean vacation.

Winship — whose successors as editor John S. Driscoll and Matthew V. Storin also would be principals in the undertaking — made it clear that he would be willing to disobey a court order to print the Pentagon Papers. If necessary, he remarked, he would dispatch Oliphant with a pile of the papers and the instructions to read them aloud on Boston Common.

So 1,700 pages of documents in a plastic bag were given in a Newton telephone booth to Tom Ryan, the Globe’s national news editor, who soon thereafter marched into the Morrissey Boulevard newsroom with a red plaid zippered suitcase stuffed with the documents. The papers later were locked in the back of a car in the newspaper’s parking lot. Winship told Attorney General John Mitchell the paper would continue printing the material, which by that time had been moved to a locker at Logan Airport before ending up in a First National Bank of Boston vault.

Expand current positive and counter-intelligence operations against Communist forces in South Vietnam and against North Vietnam. These include penetration of the Vietnamese Communist mechanism, dispatch of agents to North Vietnam and strengthening Vietnamese internal security sources.

— Covert actions recommended in May 1961 Kennedy Task Force “Program of Action”

The legal struggle over the Pentagon Papers — and over the First Amendment-rattling notion of prior restraint of speech — was one of the landmark Supreme Court battles of the 20th century. By a 6-3 vote, the high court overturned a restraining order against the Times, ruling that “any system of prior restraints comes to this Court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity” and “the Government thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a restraint.”

Katharine Graham, then publisher of The Washington Post, and executive editor Benjamin C. Bradlee looked over reports of the Supreme Court decision that permitted the paper to publish stories based on the Pentagon Papers.AP

The administration had failed to meet that burden.

“The case established that merely waving the wand of national security is not sufficient to shut down prosecutions in advance,” said Laurence Tribe, the Harvard expert on constitutional law. “There has been significant suppression of free speech in our history but this pretty much put a dramatic end to it.”

It also marked the beginning of what John Prados and Margaret Pratt Porter, writing in their 2014 retrospective, called “a period of militancy on the part of the press” — the modern era of investigative journalism that has challenged and often infuriated political leaders.

That persists to this day, as does controversy about the merits of the Vietnam War, issues about government openness, and debates about the prerogatives of a free press. For a superpower with global influence, an armada of nuclear weapons, and a civic culture rooted in the First Amendment, the “dirty questions” at the center of the Pentagon Papers never end, nor are they ever fully answered.

Spread the word