labor Explainer: A 48-year-old Union Gone in 11 Days – How Hong Kong Teachers Lost a Powerful Voice

The decision by the pro-democracy Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union to disband after 48 years, citing “enormous pressure” from Beijing and the city’s government, has silenced a major voice in civil society.

The 95,000-member union, which said it “could not see a way forward” amid political and social changes in the city, came little over a week after the Education Bureau severed ties with the group. That decision was announced mere hours after Chinese state media described the union as a “poisonous tumour” that must be “eradicated.”

The union, which represented over 90 per cent of the city’s educators, had traditionally lobbied for better working conditions for teachers, for student-orientated educational reforms, and for wider democracy for the city.

The Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union. Photo: Candice Chau/HKFP.

HKFP retraces the union’s record in supporting and defending teachers’ rights and speaking out on political issues, from colonial times to the Handover and Beijing’s national security law.

1973-97

From the beginning, the union was a major player in civil society. Founded in 1973 by a founding figure in the democracy movement Szeto Wah, its initial mission was to reform the education sector through social movements.

“The 70’s were a decade when social movements in Hong Kong flourished…” wrote academic Bernard Luk in his work detailing the union’s history. “The HKPTU was one of these emerging advocacy groups, it was also one of the largest, most robust and most influential.”

From its early years, the union lobbied the British colonial government for better pay and conditions for teachers. Its first success was securing equal pay for educators who held diplomas and those with university degrees.

Another early example of its influence was the “Golden Jubilee Incident” in 1978, when the union successfully lobbied for educators who had lost their jobs when the Education Department shut down a local school.

In the 1980s, the union also protested against construction of the mainland’s Daya Bay nuclear power plant, and against amendments to the Public Security Ordinance that would have allowed for more government control of the city’s public gatherings and its press.

At the end of the decade, the union joined with other democracy advocates to support the student-led pro-democracy protests on mainland China in May 1989, creating the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China.

Runners pose in front of the Pillar of Shame at HKU. Photo: 香港市民支援愛國民主運動聯合會 Hong Kong Alliance via Facebook.

In the wake of the Tiananman massacre on June 4, 1989, when Beijing deployed its military to bloodily crush pro-democracy protests, the Alliance began organising annual candlelight vigils to mourn victims and campaign for democracy across the border.

It also lobbied the colonial government for “mother tongue” education in schools, where English was the main medium of instruction.

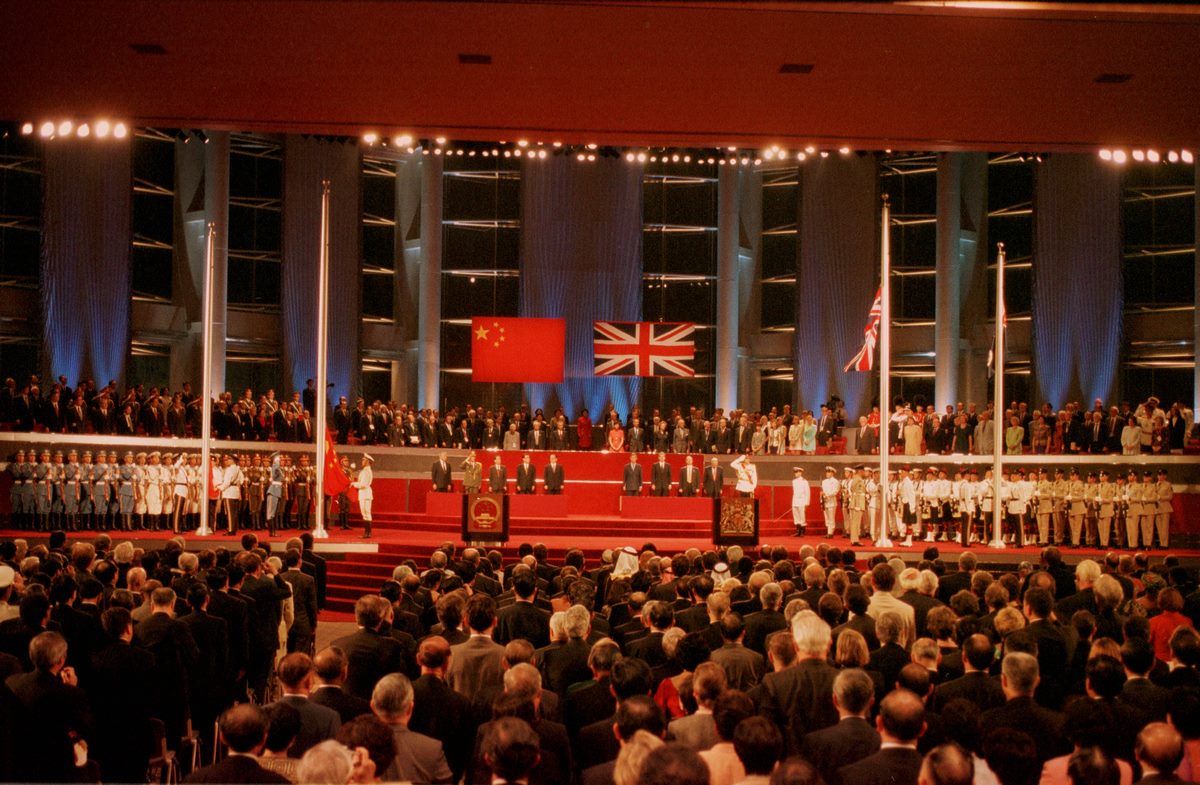

1997

After Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997, the union placed emphasis both on loving the Chinese motherland and Hong Kong by fundraising to bolster education and disaster relief on the mainland and engaging in pro-democracy activism in the city.

“The aim of education is to improve the quality of life. Our union cares about not only education, but also social and political events,” its website read in 1997.

The handover ceremony for Hong Kong held on July 1, 1997. Photo: GovHK.

“At the social level, we care about social justice. We speak for the weaker groups in society. When it comes to politics, we are determined to fight for a democratic political system so that future generations can grow up and live in a free and law-abiding environment.”

The union back then classified its social work under columns labelled “Loving China” and “Loving Hong Kong.” Under the former it listed fundraising for disaster relief and better quality education in rural China. In the latter, “fight for democracy.”

Early 2000’s

In 2003, hundreds of thousands of Hongkongers took to the streets to protest against Hong Kong government plans, later dropped, for a national security law as mandated by Article 23 of the Basic Law. The HKPTU issued a statement expressing “anxieties” over the proposal.

“The proposal actually violates the fair trial principle and deprives proscribed bodies of the right to know what exactly they are accused of and accordingly offer rebuttals. All in all, even a person who deals with no politics will not accept these proposals; the legislation should be halted at once,” a statement dating June, 9, 2003 read.

The demonstrators succeeded in shelving the proposed law for the next 17 years until Beijing imposed its own sweeping version on the city in June 2020.

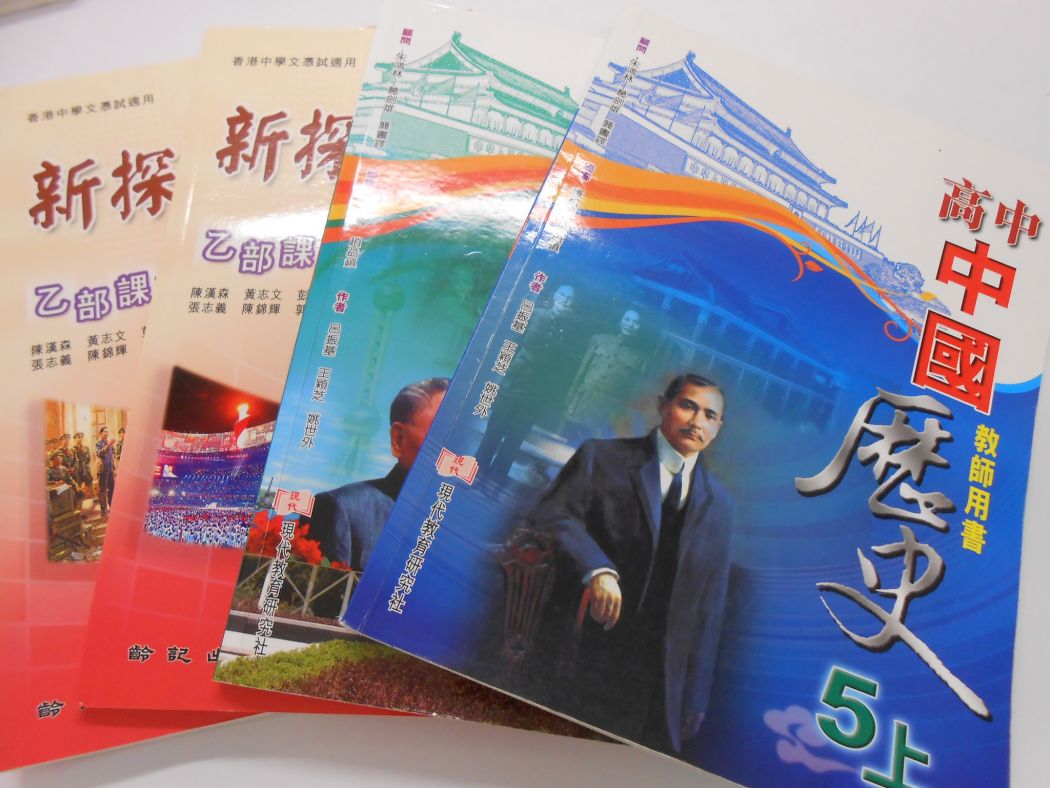

The union also protected students’ right to learn historical truths. In 2004 its chairperson Cheung Man-kwong accused publishers of a new Chinese history textbook for upper secondary school students of “rewriting history,” after lessons on the 1989 pro-democracy student protests in China failed to mention the state-sanctioned massacre that ended them.

Chinese history textbooks. Photo: Inmedia via C.C.2.0.

“They have either distorted or evaded history by not mentioning what happened during the crackdown. There is no mention of the use of force, that military tanks and machine guns were used to disperse the crowds,” Cheung told the South China Morning Post in June that year.

“Publishers are so worried their books will be banned and afraid of political pressure that they dare not tell students what really happened,” the educator said. The HKPTU then issued its own teaching materials and footage to inform students about what really happened on June 4, 1989.

2010’s

In 2012, the Education Bureau’s proposal to implement a Chinese “patriotic education” curriculum in local schools was met with widespread resistance from teachers, students and parents. A survey by the union found 70 per cent of educators opposed the plan.

The HKPTU helped organise protests and public forums against the “Moral and National Education plans,” calling on the government to listen to public opinion and withdraw them.

Student-led protests against national education legislation at the Civic Square in 2012. File Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

“The citizens have clearly expressed their request for the government to withdraw the curriculum immediately, and the government should clearly announce policies corresponding to this,” said a statement in September that year.

The national education proposals were shelved – only to be re-introduced and imposed under the national security law for this coming academic year.

An HKPTU protest on November 7, 2010 against the government’s school closure policy. Photo: Tom Grundy/HKFP.

2014 – Umbrella Movement

During the 2014 Umbrella Movement, which saw up to tens of thousands of people occupy some main roads for 79 days to demand genuine universal suffrage, the HKPTU was on the front-lines, calling for a city-wide teachers’ strike in protest at police use of force against student protesters.

“The PTU is extremely angry and strongly condemns the SAR government’s and police’s crazy actions,” its president Fung Wai-wah told the South China Morning Post at the time. The union also published teaching materials to inform students about civil disobedience.

In 2016, as schools navigated the rise of localism among young democracy activists, the union hit back at the Education Bureau’s warning to refrain from discussing Hong Kong independence in schools, saying the unclear guidelines were not in teachers’ interests.

The union celebrated its 45th anniversary in 2018, along with newly-elected Chief Executive Carrie Lam who was later to become a fierce critic.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam attended the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union (HKPTU) 45th Anniversary Reception in 2018. File Photo: GovHK.

The union celebrated its 45th anniversary in 2018, along with newly-elected Chief Executive Carrie Lam who was later to become a fierce critic.

2019 protests and unrest

In the lead-up to the mass protests which began in mid-2019 against a later-withdrawn extradition bill, the union issued a statement defending school petitions against the proposal.

It maintained its support for the protests as the months wore on. In June, it called on teachers to boycott classes for two days after clashes between police and protesters in Admiralty, demanding the government withdraw the controversial bill.

Hong Kong secondary students form human chain in opposition to the extradition bill in September 2019. Photo: Studio Incendo.

As the protests intensified, union members also held a rally in August to show their support for students against police violence.

2020 National Security Law

In early 2020, the union continued speaking up for the education sector, criticising the Education Bureau’s decision to void a question in a DSE history exam about the Sino-Japanese war which allegedly prompted sympathy for Japan.

In a statement in May, the union called the bureau’s decision “unreasonable” and accused it of placing undue psychological pressure on graduating students and suppressing intellectual freedom.

Photo: GovHK.

Since the national security law came into force following the protests, which authorities have depicted as “riots” instigated by student-aged protesters, authorities have sought to rein in the education sector.

In the months following the new law, officials insisted on the need to identify “bad apples” in the profession. Since then, the Education Bureau has disqualified at least four teachers for political reasons: one for including “Hong Kong Independence” in teaching materials, and another two over their involvement in the protests. Another was disqualified for “inappropriate” teaching materials that contained inaccurate information about the Opium War.

The pressure has not been confined to classrooms. In 2020, the bureau received hundreds of complaints against teachers, some of which took issue with what they said or posted on social media. One visual arts teacher was probed for satirical drawings on his Instagram account.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam attended the Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union (HKPTU) 45th Anniversary Reception in 2018. File Photo: GovHK.

As official scrutiny intensified, the union offered support to teachers facing complaints and investigations into their conduct both within and outside the classroom.

Changes were also being made to the curriculum. In her policy address last year, leader Carrie Lam announced plans to implement national education to foster a sense of national identity among students and to “improve” the quality of the city’s teachers.

Authorities also revamped the “Liberal Studies” subject which was designed to promote critical thinking, focusing it more on China issues and less on current affairs.

As the year drew to a close, union vice-president Ip Kin-yuen told HKFP authorities were using the education sector as a “scapegoat” for the unrest.

Lead-up to disbandment

The union kept defending teachers’ rights in 2021, despite the national security crackdown. In May, it warned that new Education Bureau guidelines allowing anonymous complaints could fuel baseless allegations against teachers.

But the situation grew dire for the union within a matter of days this summer. On July 31, Chinese state media called for it to be “eradicated.” Within hours, the Education Bureau announced it would no longer recognise the union, cutting all ties with a body that represented 90 per cent of the sector.

In the following week, Lam defended the bureau’s decision, accusing the union of politicising the city’s schools, “hijacking” the education sector and tarnishing its reputation. She declined to comment on whether the group was being investigated by law enforcement.

A queue outside Good Hope Building in Mong Kok, one of HKPTU’s service centres. Photo: Candice Chau/HKFP.

In response, the HKPTU announced it would focus on education in the future, and only use legal representation support for labour disputes.

The next day, it withdrew from the city’s pro-democracy union coalition and an international educators’ union network, Education International. The international group had on the same day condemned the Education Bureau’s decision to cut ties with the union.

The HKPTU also established a working group to promote a “positive view” of Chinese culture and history among teachers, and “foster affection for home and country” among students, seemingly in line with the objectives of Lam’s national education.

File photo: Tom Grundy/HKFP.

All this was still not enough to appease the authorities. The following day, Secretary for Education Kevin Yeung penned an open letter to the union’s members, asking them to reconsider whether the group can “truly represent them.” On Tuesday, the union announced it would disband.

Hong Kong’s teachers and students lost a loud and consistent voice defending their rights, and another pro-democracy force in the city crumbled.

Even after dissolution the pressure remained. Former chief executive Leung Chun-ying criticised the union for not following proper disbandment procedures. Attacks from Chinese state media also continued.

“HKPTU’s dissolution was a futile attempt to launder itself… will not write off its alleged crimes in the past,” an article in China’s Xinhua state news agency said on Wednesday.

Spread the word