How Rolling Stones Drummer Charlie Watts Infused One of the Greatest Rock ‘N’ Roll Bands with a Little Jazz

How Rolling Stones Drummer Charlie Watts Infused One of the Greatest Rock ‘N’ Roll Bands with a Little Jazz

Victor Coelho

The Conversation

August 24, 2021

https://theconversation.com/how-rolling-stones-drummer-charlie-watts-infused-one-of-the-greatest-rock-n-roll-bands-with-a-little-jazz-166719

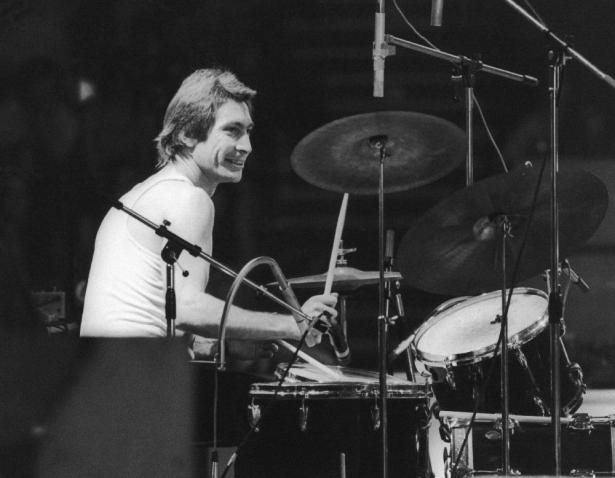

In an era when rock drummers were larger-than-life showmen with big kits and egos to match, Charlie Watts remained the quiet man behind a modest drum set. But Watts wasn’t your typical rock drummer.

Part of the Rolling Stones setup from 1963 until his death on Aug. 24, 2021, Watts provided the back-beat to their greatest hits by injecting jazz sensibilities – and swing – into the Stones’ sound.

As a musicologist and co-editor of the Cambridge Companion to the Rolling Stones – as well as a fan who has seen the Stones live more than 20 times over the past five decades – I see Watts as being integral to the band’s success.

Like Ringo Starr and other drummers who emerged during the 1960s British pop explosion, Watts was influenced by the swing and big band sound that was hugely popular in the U.K. in the 1940s and 1950s.

Modest with the sticks

Watts wasn’t formally trained as a jazz drummer, but jazz musicians like Jelly Roll Morton, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk were early influences.

In a 2012 interview with the New Yorker, he recalled how their records informed his playing style.

“I bought a banjo, and I didn’t like the dots on the neck,” Watts said. “So I took the neck off, and at the same time I heard a drummer called Chico Hamilton, who played with Gerry Mulligan, and I wanted to play like that, with brushes. I didn’t have a snare drum, so I put the banjo head on a stand.”

Watts’ first group, the Jo Jones All Stars, were a jazz band. And elements of jazz remained throughout his Stones career, providing Watts with a wide stylistic versatility that was critical to the Stones’ forays beyond blues and rock to country, reggae, disco, funk and even punk.

There was a modesty in his playing that came from his jazz learning. There are no big rock drum solos. He made sure the attention was never on him or his drumming – his role was keeping the songs going forward, giving them movement.

He also didn’t use a big kit – no gongs, no scaffolding. He kept a modest one more typically found in jazz quartets and quintets.

Likewise, Watts’ occasional use of brushes over sticks – such as in “Melody” from 1976’s “Black and Blue” – more explicitly shows his debt to jazz drummers.

But he didn’t come in with one style. Watts was trained to adapt, while keeping elements of jazz. You can hear it in the R'n’ B of “(I can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” to the infernal samba-like rhythm of “Sympathy For The Devil” – two songs in which Watts’ contribution is central.

And a song like “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” from 1971’s “Sticky Fingers” develops from one of Keith Richards’ highest caliber riffs into a long concluding instrumental section, unique in the Stones’ song catalog, of Santana-esque Latin jazz, containing some great syncopated rhythmic shots and tasteful hi-hat playing through which Watts drives the different musical sections.

You hear similar elements in “Gimme Shelter” and other classic Rolling Stones songs – it is perfectly placed drum fills and gestures that make the song and surprise you, always in the background and never dominating.

Powering the ‘engine room’

So central was Watts to the Stones that when bassist Bill Wyman retired from the band after the 1989 “Steel Wheels” tour, it was Watts who was tasked with picking his replacement.

He needed a bass player that would fit his style. But his choice of Darryl Jones as Wyman’s replacement was not the only key partnership for Watts. He played off the beat, complementing Richards’ very syncopated, riff-driven guitar style. Watts and Richards set the groove for so many Stones songs, such as “Honky Tonk Women” or “Start Me Up.” If you watched them live, you’d notice Richards looking at Watts at all times – his eyes fixated on the drummer, searching for where the musical accents are, and matching their rhythmic “shots” and off-beats.

Watts did not aspire to be a virtuoso like John Bonham of Led Zeppelin or The Who’s Keith Moon – there was no drumming excess. From that initial jazz training, he kept his distance from outward gestures.

But for nearly six decades, he was the main occupant, as Richards put it, of the Rolling Stones’ legendary “engine room.”

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]![]()

Victor Coelho, Professor of Music, Boston University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Charlie Watts, Bedrock Drummer for the Rolling Stones, Dies at 80

Gavin Edwards

New York Times

August 24, 2021

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/24/arts/music/charlie-watts-dead.html

Charlie Watts, whose strong but unflashy drumming powered the Rolling Stones for over 50 years, died on Tuesday in London. He was 80.

His death, in a hospital, was announced by his publicist, Bernard Doherty. No other details were immediately provided.

The Rolling Stones announced earlier this month that Mr. Watts would not be a part of the band’s forthcoming “No Filter” tour of the United States after he had undergone an unspecified emergency medical procedure, which the band’s representatives said had been successful.

Reserved, dignified and dapper, Mr. Watts was never as flamboyant, either onstage or off, as most of his rock-star peers, let alone the Stones’ lead singer, Mick Jagger. He was content to be one of the finest rock drummers of his generation, playing with a jazz-inflected swing that made the band’s titanic success possible. As the Stones guitarist Keith Richards said in his 2010 autobiography, “Life,” “Charlie Watts has always been the bed that I lie on musically.”

While some rock drummers chased after volume and bombast, Mr. Watts defined his playing with subtlety, swing and a solid groove.

“As much as Mick’s voice and Keith’s guitar, Charlie Watts’s snare sound is the Rolling Stones,” Bruce Springsteen wrote in an introduction to the 1991 edition of the drummer Max Weinberg’s book “The Big Beat.” “When Mick sings, ‘It’s only rock ’n’ roll but I like it,’ Charlie’s in back showing you why!”

Charles Robert Watts was born in London on June 2, 1941. His mother, the former Lillian Charlotte Eaves, was a homemaker; his father, Charles Richard Watts, was in the Royal Air Force and, after World War II, became a truck driver for British Railways.

Charlie’s first instrument was a banjo, but, baffled by the fingerings required to play it, he removed the neck and converted its body into a snare drum. He discovered jazz when he was 12 and soon became a fan of Miles Davis, Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus.

By 1960, Mr. Watts had graduated from the Harrow School of Art and found work as a graphic artist for a London advertising agency. He wrote and illustrated “Ode to a Highflying Bird,” a children’s book about the jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker (although it was not published until 1965). In the evenings, he played drums with a variety of groups.

Most of them were jazz combos, but he was also invited to join Alexis Korner’s raucous rhythm-and-blues collective, Blues Incorporated. Mr. Watts declined the invitation because he was leaving England to work as a graphic designer in Scandinavia, but he joined the group when he returned a few months later.

The Rolling Stones in 1967. From left: Mr. Watts, Bill Wyman, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones.Credit...Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis, via Getty Images

The newly formed Rolling Stones (then called the Rollin’ Stones) knew they needed a good drummer but could not afford Mr. Watts, who was already drawing a regular salary from his various gigs. “We starved ourselves to pay for him!” Mr. Richards wrote. “Literally. We went shoplifting to get Charlie Watts.”

In early 1963, when they could finally guarantee five pounds a week, Mr. Watts joined the band, completing the canonical lineup of Mr. Richards, Mr. Jagger, the guitarist Brian Jones, the bassist Bill Wyman and the pianist Ian Stewart. He moved in with his bandmates and immersed himself in Chicago blues records.

In the wake of the Beatles’ success, the Rolling Stones quickly climbed from being an electric-blues specialty act to one of the biggest bands in the British Invasion of the 1960s. While Mr. Richards’s guitar riff defined the band’s most famous single, the 1965 chart-topper “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” Mr. Watts’s drum pattern was just as essential. He was relentless on “Paint It Black” (No. 1 in 1966), supple on “Ruby Tuesday” (No. 1 in 1967) and the master of a funky groove on “Honky Tonk Women” (No. 1 in 1969).

Mr. Watts was ambivalent about the fame that he achieved as a member of the group that has often been called “the world’s greatest rock ’n’ roll band.” As he said in the 2003 book “According to the Rolling Stones”: “I loved playing with Keith and the band — I still do — but I wasn’t interested in being a pop idol sitting there with girls screaming. It’s not the world I come from. It’s not what I wanted to be, and I still think it’s silly.”

As the Stones rolled through the years, Mr. Watts drew on his graphic-arts background to contribute to the design of the band’s stage sets, merchandise and album covers — he even contributed a comic strip to the back cover of their 1967 album “Between the Buttons.” While the Stones cultivated bad-boy images and indulged a collective appetite for debauchery, Mr. Watts mostly eschewed the sex and drugs. He clandestinely married Shirley Ann Shepherd, an art-school student and sculptor, in 1964.

On tour, he would go back to his hotel room alone; every night, he sketched his lodgings. “I’ve drawn every bed I’ve slept in on tour since 1967,” he told Rolling Stone magazine in 1996. “It’s a fantastic nonbook.”

Similarly, while other members of the Stones battled for control of the band, Mr. Watts largely stayed out of the internal politics. As he told The Weekend Australian in 2014, “I’m usually mumbling in the background.”

Mr. Jones, who considered himself the leader, was fired from the Stones in 1969 (and found dead in his swimming pool soon after). Mr. Jagger and Mr. Richards spent decades at loggerheads, sometimes making albums without being in the studio at the same time. Mr. Watts was happy to work with either, or both.

There was one time, however, when Mr. Watts famously chafed at being treated like a hired hand rather than an equal member of the group. In 1984, Mr. Jagger and Mr. Richards went out for a night of drinking in Amsterdam. When they returned to their hotel around 5 a.m., Mr. Jagger called Mr. Watts, waking him up, and asked, “Where’s my drummer?” Twenty minutes later, Mr. Watts showed up at Mr. Jagger’s room, coldly furious, but shaved and elegantly dressed in a Savile Row suit and tie.

“Never call me your drummer again,” he told Mr. Jagger, before grabbing him by the lapel and delivering a right hook. Mr. Richards said he narrowly saved Mr. Jagger from falling out a window into an Amsterdam canal.

“It’s not something I’m proud of doing, and if I hadn’t been drinking I would never have done it,” Mr. Watts said in 2003. “The bottom line is, don’t annoy me.”

At the time, Mr. Watts was in the early stages of a midlife crisis that manifested itself as a two-year bender. Just as the other Stones were settling into moderation in their 40s, he got hooked on amphetamines and heroin, nearly destroying his marriage. After passing out in a recording studio and breaking his ankle when he fell down a staircase, he quit, cold turkey.

Mr. Watts and his wife had a daughter, Seraphina, in 1968 and, after spending some time in France as tax exiles, relocated to a farm in southwestern England. There they bred prizewinning Arabian horses, gradually expanding their stud farm to over 250 horses on 700 acres of land. Information on his survivors was not immediately available. Mr. Doherty, the publicist, said Mr. Watts had “passed away peacefully” in the hospital “surrounded by his family.”

The Rolling Stones made 30 studio albums, nine of them topping the American charts and 10 topping the British charts. The band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1989 — a ceremony Mr. Watts skipped.

Eventually the Stones settled into a cycle of releasing an album every four years, followed by an extremely lucrative world tour. (They grossed over a half-billion dollars between 2005 and 2007 on their “Bigger Bang” tour.)

But Mr. Watts’s true love remained jazz, and he would fill the time between those tours with jazz groups of various sizes — the Charlie Watts Quintet, the Charlie Watts Tentet, the Charlie Watts Orchestra. Soon enough, though, he would be back on the road with the Stones, playing in sold-out arenas and sketching beds in empty hotel rooms.

He was not slowed down by old age, or by a bout with throat cancer in 2004. In 2016, the drummer Lars Ulrich of Metallica told Billboard that since he wanted to keep playing into his 70s, he looked to Mr. Watts as his role model. “The only road map is Charlie Watts,” he said.

Through it all, Mr. Watts kept on keeping time on a simple four-piece drum kit, anchoring the spectacle of the Rolling Stones.

“I’ve always wanted to be a drummer,” he told Rolling Stone in 1996, adding that during arena rock shows, he imagined a more intimate setting. “I’ve always had this illusion of being in the Blue Note or Birdland with Charlie Parker in front of me. It didn’t sound like that, but that was the illusion I had.”

Spread the word