Last week marked the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Blair Mountain, the largest labor uprising in U.S. history. In 1921, around 10,000 coal miners in Logan County, West Virginia, who had been trying to unionize with the United Mine Workers of America went to war against about 3,000 coal bosses, state police, private security forces and scabs. For five long, bloody days, those miners in their red bandannas — the Red Neck Army, as they called themselves — held the line, fighting like hell for their futures and their families. Over a million shots were fired, over a dozen people died, the coal bosses dropped bombs and poison gas on mining camps, and the conflict ended only because of federal intervention. Blair Mountain was a pivotal moment in U.S. labor history and a hallowed chapter in the struggle for workers’ rights.

But despite Blair Mountain’s dramatic resolution, it remains a strangely little-known historical footnote outside of local publications, labor history groups and labor-friendly progressive media outlets. The fact that this centennial passed mostly unmarked is not a coincidence. As Tennessee-based journalist Abby Lee Hood explained in a recent New York Times op-ed, a coal-funded nativist organization called the American Constitutional Association has worked for decades to intentionally obscure the battle’s history, as well as the even longer tradition of militant, interracial labor organizing in the coalfields. The story of Blair Mountain has been repressed by those who would prefer to keep workers in the dark about their own collective power, as have so many other working-class stories.

Even contemporary labor stories are hard to come by in most major media outlets, and labor reporters like me make up a scrappy but still tiny cohort of the media itself. And bosses are able to exploit that lack of attention for their own agendas. For example, have you heard about the 700 St. Vincent Hospital nurses in Worcester, Massachusetts, who have been on what is now the longest-running strike in state history? How about the Nabisco strike, which had exploded to include over 1,000 members of the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers’ International Union in five states? And speaking of coal miners, did you know that over 1,100 members of the United Mine Workers are on strike right now in rural Alabama?

The Warrior Met Coal Strike has been going on since April 1, and the striking workers and their families have been weathering economic pressure, company hostilities and violence on the picket lines with next to no media attention or support from local or state politicians. Multiple vehicular attacks on the striking workers have been documented, with several people, including a miner’s wife, hospitalized; workers have been surveilled by company drones and hassled by police, and I’ve heard stories of multiple workers’ being threatened by scabs and company employees.

Coal mining is a dangerous job, and as history has shown time and time again, so is standing up to coal bosses.

Every single one of these strikes (and many more besides) should be front-page news, and each of their rank-and-file leaders should be handed microphones and invited in front of news cameras to tell their stories and show other workers that they can do it, too. The untold history of American labor includes so many diverse voices, experiences and struggles; it has touched every person living on this stolen land, and it has shaped the way today’s workers move through society. Of course, it’s in the best interest of capital and the controlling class to tamp down as much of that generational knowledge and solidarity as possible. We can’t have workers getting ideas, you see, and robbing people of their own history is a surefire way to convince them that things have always been this way and that resistance is futile.

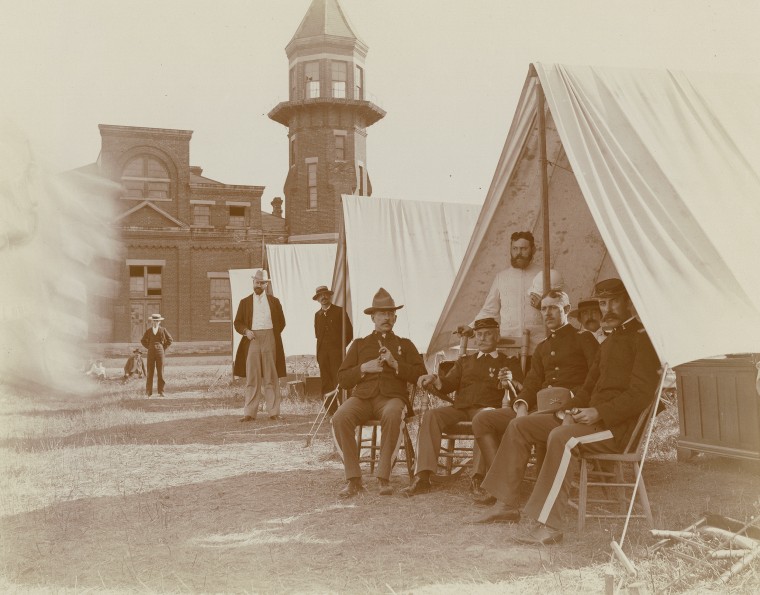

Troops sit outside their tents during the Pullman Railroad Strike in Chicago in 1894.Chicago History Museum / Getty Images

Even Labor Day has a less than auspicious history. The holiday was signed into federal law with a stroke of President Grover Cleveland’s pen in 1894, during an era marked by massive strikes, widespread labor unrest and the campaign for the eight-hour workday, a movement led by labor radicals and anarchist revolutionaries. That year alone, 125,000 Pullman railroad workers across 29 railroads had walked off the job to protest wage cuts.

But while there is some historical disagreement over its exact origins, Labor Day has subsequently been used to direct workers away from celebrating International Workers’ Day, also known as May Day, with all of its revolutionary, anti-capitalist connotations. In 1955, during a crackdown on leftist organizations and labor unions, the government designated May 1 as “Loyalty Day”; even now, the president issues a “Loyalty Day” proclamation every year on a day the rest of the world dedicates to its workers.

That history may have been buried, but workers’ bodies keep the score. This is all why it’s so incredibly important for us to remember Blair Mountain and to stand in solidarity with struggles like those of the St. Vincent nurses, the Nabisco workers and the Warrior Met Coal Strike. With each new labor conflict, we have a fresh opportunity to stand up against capitalist tyranny, support our co-workers and communities and take back more of what’s been stolen from us.

This Labor Day, take a moment to remember those collective radical roots and find inspiration in the bravery and sacrifice of generation after generation of workers who had nothing left to give but still gave everything they had. As Florence Reece, a coal miner’s daughter turned lifelong labor activist, wrote back in 1912 as her father held the picket line, which side are you on?

[Kim Kelly is a freelance journalist, organizer and author based in Philadelphia. Her work on labor, politics and working-class resistance can be found in Teen Vogue, The Baffler, The New Republic, The Washington Post and many others.]

Spread the word