“When history is written as it ought to be written, it is the moderation and long patience of the masses at which men will wonder, not their ferocity.”

—C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins

“The Haitian movement, though the most pivotal to the abolition of slavery in the Americas, is the most neglected—we all owe a great debt to Haitians and must pay it.”

—Margaret Prescod, introduction to Selma James’s Our Time Is Now

On July 7, 2021, the illegitimate president of Haiti Jovenel Moïse, who had led Haiti since 2017, was assassinated in an attack on his home in the outskirts of Port-au-Prince. Before his death, despite his term officially ending on February 7, 2021, Moïse was holding onto power, with support from death squads on the ground as well as the Joe Biden administration (a continuation of the Donald Trump administration policy) and United Nations. For months, Haitians came out in large protests demanding Moïse step down. At the same time, the Biden administration continued and continues to deport Haitians at alarming rates.

Ariel Henry was sworn in as the acting president of Haiti on July 20, 2021, having been chosen as the next prime minister by Moïse shortly before his assassination. The Core Group—made up of ambassadors from the United States, France, Canada, Germany, Brazil, Spain, the European Union, and representatives from the United Nations and Organization of American States—have put out a statement throwing their support behind Henry.

Haitian authorities arrested the head of Moïse’s security team as part of its probe into the assassination and issued an arrest warrant for Supreme Court Justice Windelle Coq Thélot. Colombian mercenaries have also been linked to the assassination, with the Pentagon confirming that four of the accused mercenaries had received U.S. military training at Fort Benning in Georgia. Formerly known as the School of the Americas (dubbed by critics the “School of the Assassins”), the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation at Fort Benning has been used for decades to train Latin American soldiers in combat, counterinsurgency, and counternarcotics. Since then, the judge presiding over the investigation of the assassination quit because one of the court clerks was also found dead.

On August 14, 2021, a devastating 7.2 magnitude earthquake hit Haiti. At the time of writing, the death toll has risen to around 2,200, more than 12,000 people have been injured, and over 7,000 homes have been destroyed. Many hospitals have also been damaged, with ones still operating reporting overcapacity of patients and shortages of medical supplies. Two days after the quake, Tropical Storm Grace swept into Haiti, bringing heavy rain and winds.

Camila Valle: Thank you both for joining me to talk about what is happening in Haiti. A lot has transpired: Jovenel Moïse’s refusal to step down, his subsequent assassination, Ariel Henry’s swearing in as the new prime minister, the death squads on the ground, the earthquake, the tropical storm, and of course the subjection of Haiti to imperialist entities (mainly the United States, United Nations, and Organization of American States ). Before we get into all this, could you talk about the historical roots of the current conjuncture?

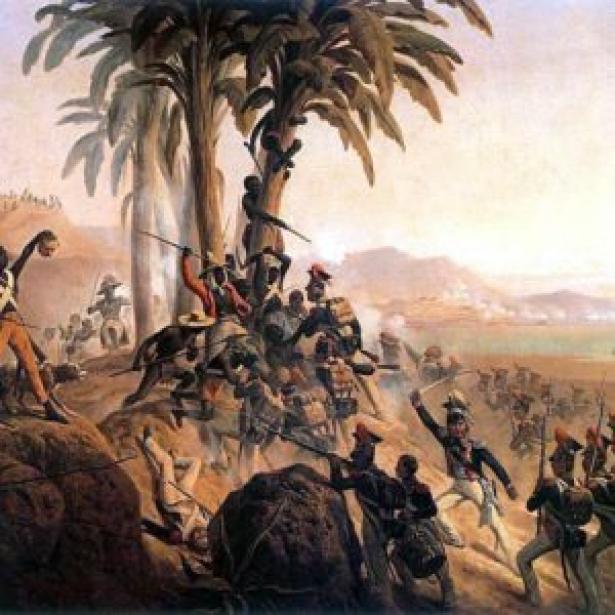

Pierre Labossiere: The first thing to say is that the current situation has roots in the historical struggle of the people of Haiti, a people whose foremothers and forefathers were kidnapped from Africa and brought to this land to work as beasts of burden, to make fortunes for people who kept them as enslaved labor. They fought against slavery and successfully defeated it in 1791, founding the independent nation of Haiti on January 1, 1804. But the struggles for our liberation have not stopped, because Haiti was this odd country founded by enslaved people. It established itself as a free nation dedicated to the abolition of slavery; it declared itself a sanctuary country for oppressed people, particularly enslaved Africans and Indigenous people. They could come to Haiti to be recognized as citizens and their freedom defended. This is the background.

But the slavocracy, the slave empires—we are talking France, Britain, Spain, later the emerging nation of the United States, which had Africans working as enslaved labor—wanted to destroy this example of freedom and successful revolution. Since that time, Haiti has been in the throes of this struggle, which has impacted the people inside Haiti. What these nations did was foment and put in power people and governments that would become enemies of the mass Haitian population, as they tried to establish the old colonial system of exploitation of the majority for the enrichment of the few. So the people of Haiti have continuously struggled against this colonial view and system of exploitation. We are seeing a continuation of this today.

There was a turning point in 1915, when the U.S. government invaded Haiti. At the time, the people’s struggle in Haiti was about to take power, because peasants’ land had been taken and was being given to foreign entities, particularly from the United States, and the people of Haiti said, “No, we are not going to tolerate that.” There was a massive uprising and the U.S. Marines came in, on the side of the Haitian elite and their foreign allies, to “restore” the country and prevent the people’s movement from taking power. Since then, the United States has become the dominant decider in Haiti’s daily affairs, and we have been struggling against this U.S. domination, our primary domination. In recent times, François “Papa Doc” Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier were the most brutal expressions of this class struggle, this class warfare being organized against the people in order to maintain the old colonial system of exploitation intact.

In 1986, people rebelled, successfully overthrowing Duvalier, but the United States has since continued to try to bring back the Duvalierist forces and keep them in power. After Duvalier fled, we had four years of the Duvalierist military-dominated government, which was extremely brutal in its repression. In 1990, the people elected Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the parish priest who was a leader of the new movement for liberation. He was the first democratically elected president of Haiti and lasted only seven months in power. On September 30, 1991, there was a coup organized by the United States and carried out by the Haitian military. Over five thousand people were massacred, there was massive resistance by the population with international solidarity, and President Aristide returned two years later to complete his term in office. René Préval was elected in 1996, in the first free transition of power from one elected government to another, but the United States continued to undermine the democratic process.

I have to note that, in 1987, even at the height of the military dictatorship, the people of Haiti successfully drafted a new constitution based on popular participation and voted overwhelmingly for it, enshrining the many gains of the democratic movement. Of course, the constitution was never respected by the military, the Duvalierists, or the United States. In 2000, there were democratic elections and President Aristide was elected for his second term in a landslide victory. But the United States mobilized its forces and massively undermined the march for democracy, the implementation of democratic rule in Haiti. In 2004, the U.S. government under George W. Bush carried out the second coup (George H. W. Bush was responsible for the first in 1991), leading to the killing of close to ten thousand people by right-wing forces—the old Haitian military forces that President Aristide had disbanded, coupled with various mercenaries and killers from Haiti, including the death squad Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti, similar to the Tonton Macoutes, the henchmen of Papa Doc and Baby Doc Duvalier. They actually were not able to carry out the coup d’état, so the special forces of the United States, France, and Canada came in and overthrew and kidnapped President Aristide. But the Haitian people never accepted this coup d’état and resistance has continued to this day.

Since then, Haiti has been under occupation by the United States, France, and Canada, but using the United Nations as a cover to make it acceptable and palatable to the rest of the world. UN forces have really been carrying out U.S. foreign policy; they have massacred people in poor neighborhoods and various communities throughout Haiti, because they have kept up the demonstrations against the rotten system of exploitation, demanding their democratic rights and that the people they elected be returned to office. So they are being massacred.

The Tonton Macoutes, which the governments of Papa Doc and Baby Doc had set up, are brutal death squads that have continuously been on the scene, even under different names. One name was the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti, during the first coup. Now they are known as “gangs,” but this is just a way to throw people off. When people hear “gangs,” they think these are forces opposed to the government, but this is not true. These are government-paid groups of killers, death squads that are working with the government. In October, even the office of the secretary general of the United Nations, António Guterres, made a statement praising Jimmy “Barbecue” Cherizier, who is a brutal killer, one of the most notorious death squad leaders. He actually formed the federation of the so-called gangs of the death squads, G9 Family and Allies. That federation was organized by the Haitian government, which paid them millions of dollars under the cover of so-called disarmament. It was really a way to provide them with money and more ammunition so they could kill people, create a campaign of terror throughout Haiti, and operate these massacres today. Before, at the beginning of the coup of 2004–05, UN troops carried out a number of massacres—I can think of at least four off the top of my head. Now, it is not really UN troops or the Haitian police. It has been passed onto the G9 Family and Allies and the death squads, in what has been presented to the world as gang warfare. But everybody in Haiti knows that is not true.

Margaret Prescod: I’m Bajan [from Barbados], and Haiti has always been important to us in the Caribbean region. The Haitian Revolution happened decades before the Emancipation Proclamation in the United States, and there was great fear that what happened in Haiti would happen in other slaveholding countries in the Americas. Indeed, in Barbados for example, the great Bussa’s Rebellion of 1816 was definitely inspired by the Haitian Revolution. If you look throughout history, practically all of those islands of the Caribbean, from Granada to St. Vincent, had uprisings—some greater, some smaller, but all very much inspired by the Haitian Revolution. Some of the people who took part in and helped organize what is considered to be the largest slave revolt in the United States, the 1811 revolt in Louisiana, were Haitians brought over by their slave masters when they fled Haiti after the revolution. The Haitians who were brought over immediately started mobilizing and organizing with other enslaved people in the United States, which was quite remarkable given the differences in language and so on. I say this also because the huge expansion of the United States as a result of the Louisiana Purchase was really due to the Haitian Revolution forcing France to leave the territory.

In that same period, Haiti offered enormous assistance to Simón Bolívar, the liberator of Latin America, who twice had to flee for his life. He fled to Haiti post-revolution, where he was given refuge, and Haitians sent him back with fighters, weapons, and resources. Today, there is even a place in Caracas where Haitians died fighting for the liberation of Latin America. It was a huge international event. And this is part of the price Haitians have paid ever since. Some of this story is told in C. L. R. James’s The Black Jacobins.

Folks know that if you really want to kill people and brutalize people, you first dehumanize them, and there has been such a dehumanization of Haitians in particular. It is the thread of the devaluation of Black lives, going back to slavery and the creation of race in a lot of ways. When I go to Haiti, I see the level of poverty, the level of dehumanization of people, the stark class divide between the Haitian majority—the grassroots people, a lot of them dark-skinned Black people—and the elite. One of the most recent times I visited Haiti, I was there with a television program trying to get the story after the Lasalin massacre, orchestrated by Barbecue. Barbecue Cherizier is now being put forward as some kind of revolutionary. What ordinary Haitians described to me, the way the killings were carried out, the way these death squads operate—it is sheer inhumanity. It was not just killing people, but burning them alive, chopping them up. They took me to the body of a pregnant woman who was burned alive, it was still there. It is just a level of brutality that is tied to the absolute dehumanization of the Haitian people. It sends a clear message: either you toe the line, you do what we want, what is in the best interests of the powers that be, or this could happen to you too. Haitians are used as examples to other peoples; the threat that if you dare rise up, this is what can happen to you.

CV: You have both touched on the evolution of the imperialism Haiti has suffered as endless retribution for its revolution. There are, perhaps, more overt expressions of this, such as coups against democratically elected leaders, dictatorships, and occupations, but there is also a more “palatable” kind of imperialism Haiti is subjected to by global institutions and organizations that are dominated by the West, the United States in particular, that give a facade of “neutrality.” You have the United Nations, World Bank, International Monetary Fund, the NGOs, and so on, that play an occupying and policing role, that murder and rape, that impose debt and austerity, and that even bring in things like the cholera epidemic. For example, Haiti is often talked about as a main target of “aid tourism” or as a “republic of NGOs.” Could you say more about this?

PL: I must start with the question of debt. Haiti was forced to pay France the equivalent of $21.7 billion in exchange for the recognition of Haiti’s independence. Haiti was one of the first nations to arrive in the postcolonial period and it was immediately saddled with debt and paying reparations. The connection is very clear. It basically set the stage for the question: How come all the former colonies are the ones that all of a sudden owe all this money to their former colonizers? It should be the other way around! Back in 2003, President Aristide called for restitution and reparation. Restitution referred to the restoration of the money it had been established that Haiti had paid, plus reparations for the crimes of slavery, even though the French government passed a law recognizing the slave trade and slavery as crimes against humanity. France essentially participated in the 2004 coup so they wouldn’t have to pay.

After the revolution, Haiti was a tiny little island in the Caribbean, completely surrounded by the empires of the time, which enslaved Africans just like Haiti had under French colonialism. France threatened to bombard Haiti if it didn’t pay the money back. There was an immediate threat also of the re-enslavement of our people. France was aided in this by the United States, which at the time was a young emerging nation but very much engaged in the slave trade, as well as Britain, Spain, and other European countries. Haiti was forced to pay the money, first to France, and then to the United States when it took over in 1915. We started paying the debt to the United States, with the payments only ending in 1947.

The Haitian government, after the revolution, during which it was under direct compulsion to varying degrees from the great powers, leading up to the twentieth century U.S. invasion and occupation, was very similar to the present-day lackey governments of foreign powers. The great powers managed successfully to use the local elite to set up a lackey government that went against the wishes of the people, who wanted to fight, to resist. That really started the impoverishment. Money that should have been invested in building the country’s infrastructure, building schools, roads, irrigation canals, supporting our local economy, supporting the development of the country, was all going to France instead. Actually, a lot of the modernization of Paris is linked to the money Haiti had been paying France. Mind you, this money was not being paid by the Haitian elite or the companies operating in Haiti exploiting our people. It was paid by the labor of the Haitian peasantry, which is still overwhelmingly taxed to the point where they work but do not benefit from the services their tax money is supposed to provide. So what you have is the elite, local and foreign, that is not really paying taxes, and all of this wealth that is being produced by and taken away from the Haitian peasantry. It is a transfer of wealth and power very reminiscent of the kind of expropriation during slavery, the same type of system where the labor of the people was being extorted and going into the pockets of foreign powers.

Now, the NGOs are a continued exploitation of our people. What we have in return for all this expropriated wealth is a number of NGOs invading Haiti, using the misery of our people—in the form of writing beautiful things abroad, taking photos of starving children, and the like—to ask for money to line their pockets and not presenting the reality of the situation. So much so that when the people of Haiti are standing up and fighting for their liberation, there is complete silence. It is always “all the people are hungry, they are poor, they don’t have access to medical care,” but never is the connection made between the exploitation of our people and the misery to which we are subjected. Never is our resistance front and center.

MP: Haiti is a clear example of what has been called the NGO industrial complex. Haiti has more NGOs per capita than any other country in the world, yet it remains the most impoverished in the Western hemisphere. NGOs are also often sexually violent. A few years ago, reports came out of Oxfam workers raping women and girls in Haiti. It goes back to Haitian people being seen as lesser than, and a number of NGOs go in with savior complexes and that kind of missionary attitude of superiority. They treat the people they are supposedly trying to help in a particular way. Then, of course, the NGOs also have a particular lifestyle—where they live, the type of vehicle they drive, and so on—that is far beyond the reach of an average Haitian person. So you have a whole sector of the population funded by this NGO money, almost like a particular expat community, that is really outside of the day-to-day reality of Haitian people. You also saw this after the 2010 earthquake, where you had the largest and major NGOs flooding the country, collecting massive amounts of money, because I think people in the United States were shocked when that earthquake happened. A lot of people had no idea about Haiti before that, so they donated millions and millions of dollars. What happened to that money? A good question to ask the NGOs. The Red Cross raised half a billion dollars and only built six homes. Just outrageous.

As Pierre pointed out, there has been continued resistance since 2000. I have been in Haiti at various periods from 2000 up to COVID basically, and you could really see that there was a movement in the streets. In the United States, the left can get very confused about what is going on in Haiti. People like to say that it is complex. Well, it is a complex situation because you have the powers that be, the United States and its Core Group, running so many operations on the ground, and you have Haitians, who perhaps are the Haitians who can afford to travel and have connections and so on, running around to the World Social Forum and places like that, giving the impression that they are the voice of Haiti and the movement. But if you scratch the surface of some of these people, you would see that they were involved, if not directly then indirectly, in the coup against President Aristide. They tend to surface at particular moments in the struggle of the Haitian people. They come across with the right rhetoric or revolutionary language, but people on the ground know very well who they are and really do not trust them. Rather than supporting the demands coming from the Haitian grassroots people themselves, they handpick which demands to support or not, they hand pick their leaders. But they create a lot of chaos and confusion. To me, this is another level of imperialism, what I am calling the solidarity industrial complex, which you see really developing, bypassing the Haitian grassroots, propping up a selective group of people. Selected by whom? Who knows, they meet in the U.S. embassy privately, they have all kinds of deals and money.

The latest outrage is the outspoken support of Barbecue by a prominent left-wing journalist who is frequently presented as an expert on Haiti. He is putting forward that Barbecue is a revolutionary. In Haiti, I took testimony after testimony of people talking about Barbecue’s connection with the police (he is an ex-cop himself), about his orchestrating these death squads, these massacres, and now he is being rehabilitated as some kind of revolutionary. You see, this is the kind of COINTELPRO operation that really is insidious, and I do not say that lightly. I do not believe it is innocent or uncoordinated in some way, because everybody knows—the Biden administration, the United Nations, and the OAS, which played a slimy role with Moïse—in contrast to the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) countries who were opposing what the head of OAS was doing with regard to Haiti. A well-meaning person could read that and say, “Oh, wow, look at this. You’ve got this new revolutionary with all this revolutionary rhetoric.” The man is a mass murderer. It is extremely dangerous.

PL: This appears to me to be well coordinated, because the evidence is overwhelming. Barbecue has been named first and foremost by his victims, but also upon investigation by none other than the United Nations and the U.S. Department of the Treasury, even under Trump. For this same man to have so-called left-wing journalists praise him as a revolutionary is just outrageous. It shows the racism of a certain sector of progressive media; to them, Haitian lives do not matter. Haitian people take great note, they know who has been killing them and who sides with them.

CV: How do President Aristide and the Lavalas movement fit in this context?

MP: An important question. The Fanmi Lavalas movement and party, associated with Aristide, did not follow the traditional left sectarian party line. Aristide was a liberation theologist, he was a man of the people. Lavalas was not connected to a particular left grouping, it was really a mass movement of the people, which means many have had a hard time trying to categorize it, putting it in a particular bag, you know? I say this because there seems to be a lot of confusion around Haiti, even from people who may be very clear, for example, when it comes to Venezuela and how the United States went after the late Hugo Chávez. They are much less clear when it comes to Haiti. Why is that? It is worth thinking about.

PL: This is, again, about the devaluation of Black lives. I am not just quoting some cliche here, I mean it deeply. The Lavalas movement and political organization is a continuation of the struggle of our ancestors, as expressed through their various organizations over the last two centuries. Lavalas is the continuing expression, the continuing completion, of the Haitian Revolution. Our enslaved foremothers and forefathers had a political vision. They had a vision of society that should be organized in an egalitarian way, and it was reflected after independence in the kind of society that we organized. However, there is this racist view that is continually being proposed: that Black people did not have a history before slavery, as if we did not produce or invent anything. This is very pervasive in the left movement, not just the right, so that, when it comes to Haiti, unless you are pro-this or pro-that, unless you are categorizable from the outside, as Margaret was saying, then you do not count according to an established left. Well, in Haiti, our people rose up because the conditions of exploitation that were crushing their humanity forced them to rise up and say, “No. We are human beings and we are not tolerating this. We used to live a certain way in Africa and we want to rebuild society based on that.” It is not just me saying this. This is part of the oral tradition and the way that people have organized their societies post-independence.

It is a dismissal of Black resistance and organization. For example, people will often say that Haiti is an informal economy. What the hell is that? We are talking about an economy that over centuries has provided for the lives of millions of people—and very well. What is informal about that? What they consider formal is actually what they are trying to impose on the majority of Haiti, not responding to or meeting the needs of the population in terms of nutrition, shelter, health care, culture, or any of that. For the past eighteen years, the occupation, which is imposing on us this new economic system, has created the worst conditions in Haiti ever. Complete inequality, the enormous gap between the haves and the have-nots, destruction of the local economy and national production of food, and so on. Whereas, during the brief ten-year democratic interlude in Haiti, with Lavalas and President Aristide, who represent the vision of society of our ancestors, we have built more schools and hospitals than during the entirety of the first two centuries of independence. I would not say that everything was rosy, but there was a march toward improving conditions, a mobilization of society to change old structures and create new ones. Margaret mentioned The Black Jacobins. I love The Black Jacobins because it really presents our history as human beings struggling to be free, to liberate ourselves. Today is a continuation of that struggle.

MP: I just want to say something about the often repeated “Haiti must have elections as soon as possible.” Everybody on the ground, even CARICOM, knows that elections are not possible given the current situation. There had been a grouping of those who were opposing Moïse, including the Lavalas, with their own demands. One was a demand for an interim period to get things organized in a certain way so that elections would be possible.

PL: Absolutely. The Creole name for the proposal is Sali Piblik, public safety, and you will see it written all over Haiti in different neighborhoods. “Let’s have elections, let’s have elections”—that is the United Nations, and by that I also mean the United States, as the United Nations does their bidding. When they use the word elections, they make people think that there is participation. The system of elections they have imposed on Haiti, keeping in mind the dominance of the United States over Haiti, is the system of elections under Jim Crow, whereby the mass population is excluded from the voting process. Their voices are excluded. In Haiti, it is no longer one person, one vote. They have carved it out so as to exclude mass participation. Only a handful of people vote. In spite of this, they make sure to use computer systems to preselect and populate the vote. Everything is already in the bag and all they want is people to show up, while they set up artificial voting lines so that journalists can walk by, snap a photo, and show the world.

Margaret and I witnessed the 2016 elections in Haiti and we saw how many people were excluded from voting. Information on this came out later. They know that this is the way to fool the world one more time. There was an election, but those in office do not represent the majority of the population. The function of these elected officials is to sign off on things, to agree to loans, to authorize the theft of the resources of the country because they have the legal authority to do so. Who then has to pay back these loans at usurious interest rates? The people of Haiti, as usual, who did not elect the people in charge. Those people were imposed, yet we are the ones who have to then pay those loans back to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. It is another level of exploitation in the continuing system against our people. People are saying, “Enough, we are sick of it.” They wanted Moïse to step down immediately, as he was imposed by the United States, United Nations, and OAS on behalf of the imperialist powers.

We the Haitian people will pick the credible, honest, competent Haitians who can form a government to represent different sectors, rebuild the institutions that have been destroyed by the eighteen-year occupation and the Moïse dictatorship, start responding to the needs of the population in terms of clean drinking water, hospitals, schools. For example, many of our teachers are not being paid; Haiti has tons of money, but there is no money for education because it is all going into the pockets of the NGOs, foreigners, and local elite. The proposal is to start this phase of cleaning up so that, after three years of this transition period, elections can be organized and the people can freely vote for the representatives of their choice. One person, one vote. That is what Sali Piblik is about.

CV: We have been talking about this throughout, but it would be useful to break down the significance and legacy of Aristide charting an independent course for Haiti. He prioritized food security, health, education, agricultural cooperatives, a higher minimum wage, reparations from France, democracy within the country, independence from foreign entities, and so on. What has been the impact of Aristide and the Lavalas movement?

PL: In 2000, President Aristide and Fanmi Lavalas published a book. Everybody except Haitians knew that Haiti was a rich country with many resources. They kept telling us that we were a very poor country, that we had nothing, and there was no real pride in Haiti except that we defeated the French. But we had no idea. The Lavalas movement really made it a point to make Haitians aware of our history of resistance and exploitation, and how we ended up where we are today. They also had a program called Investir Dans L’Humain, investing in people. It spelled out Haiti’s various resources and how they could be used in the development of the country, meaning to improve living conditions so that people can have a good life as befits them as human beings, with dignity.

For example, President Aristide and his government invested a lot into creating an equitable system of justice. He disbanded the Haitian military in 1995 (it was only remobilized by Moïse), which was no small or easy thing. The Haitian military used to take 40 percent of the national budget. It was created by the United States in the wake of the 1915 invasion to be at war with the population, creating coup d’états, repressing people, carrying out torture and massacres. President Aristide disbanded it, created a civilian police force, and invested that 40 percent in social services and the local economy. He decommissioned Haiti’s equivalent of the Pentagon and donated the building to the women’s movement, which created the Ministry for Women’s Affairs to deal with the problems that the majority of women in our society face. He invested in schools, hospitals, local food production, and the like, reenvisioning Haitian society in a way that benefited the population, and Haitians were really responding to it. For the first time, Haitians stopped going abroad and were coming back home to invest in the country. Ever since the U.S. occupation of 1915, Haitians have fled Haiti because of the war, both by the U.S. and Haitian militaries against the Haitian population. People were fleeing to Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and some of the other islands. The conditions to build the country were being created by Aristide and the Lavalas movement.

Another very important thing is that, for the first time, we as Haitians were celebrating Creole, our national language, which is spoken by basically 100 percent of the Haitian population. French was the only official language, but was only spoken by probably 10 to 15 percent of the population. Haitians were made to feel like foreigners in their own land. You would go to court, for example, and everything was in French, so people would not understand what was being discussed about their own lives, the decisions that were being made about their lives. President Aristide was the first to take the oath of office in Creole. This was major. The impact of it in Haiti has been phenomenal. When he went to the United Nations, his addresses were in Creole. They had to go get him an interpreter! He established this kind of respect and made Haitians proud. While he was in office, people were very proud to say they were from Haiti.

Finally, President Aristide established that Haiti was indeed part of Africa and part of the Caribbean. He was very active in CARICOM and in forging greater collaboration between the nations of Africa, Haiti, and CARICOM. There is much to say about what was accomplished during President Aristide’s tenure of office and the Lavalas government.

MP: Pierre, I’m really glad you mentioned women. I’m part of the Haiti working group of the Global Women’s Strike. We do what we can to support women and their projects on the ground, whether it is food production or helping take care of people. We know very well how COVID has exposed how dependent society is on people who take care of you, the caregivers who are overwhelmingly women. Women have played a central role in the deep resistance in Haiti, going back to the days of the Haitian Revolution and since, ensuring that the children eat even if the adults do not, providing shelter, comfort. I went to Lasalin following the massacre there, and the women were showing me the houses that had been built by President Aristide and were being attacked by these paramilitary death squads. They talked about the hospital that had opened and then was shut down. The workload that the women carry, everything they do, not only to maintain their families, but also to maintain the resistance, really cannot be underestimated.

The university of the Aristide Foundation was also set up and attended by the children of market women, tap taps drivers, agricultural workers, and so on. It was their main opportunity to go to a university where they would not be looked down on. It began as a school of medicine, but was shut down and its campus used as a military base by the United States after the second coup. When President Aristide returned, he said his focus would be education. He and the former first lady, Mildred Trouillot, came back in early 2011 and, by that September, the campus was reopened. I’ve been to several of the graduations and there are just thousands of very happy Haitians, so proud of their children who have graduated as doctors, lawyers, nurses, therapists. They now have an agronomy department and are building a teaching hospital. They are also working to establish relationships with people in the academy here in the United States and the Caribbean, as well as to bring visiting professors and doing all kinds of things virtually due to COVID. It has been a very bright spot given all the bad news coming out of Haiti. At the last graduation I attended, there was a key opposition-media television person who was totally blown away by what he saw and even admitted in a news report that, despite whatever criticisms he had come to prove, the university was a huge accomplishment. It is something of which every Haitian really should be proud. To me, this is a continuation of the kind of work by Aristide and the Lavalas movement that Pierre described. Despite the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the rest of them cutting off money to the Aristide administration, the Lavalas were able to accomplish what for a few hundred years did not happen. It speaks to their dedication, understanding, and simpatico relationships with the Haitian people.

PL: The Aristide Foundation for Democracy, another institution that President Aristide established, was founded with the grassroots women’s movement on March 8, International Women’s Day, with the women in the leadership.

CV: We have spoken at length about the historical threads running through Haiti and the present moment. Let us turn to the specificities of the current situation, perhaps starting with the assassination of Moïse itself. Haitian authorities have arrested the head of Moïse’s security team as part of its probe into the assassination and issued an arrest warrant for Supreme Court Justice Windelle Coq Thélot. Colombian mercenaries have also been linked to the assassination, with the Pentagon confirming that four of the accused mercenaries had received U.S. military training at the School of the Americas. Since then, the judge presiding over the investigation of the assassination quit because one of the court clerks was also found murdered. What do you say about the assassination, who may be behind it, and where things stand now?

PL: The reality of the situation is that it’s confusing. People in Haiti are looking at it as more of a question of infighting among a group of partners in crime, or co-opted individuals, with Moïse at the head. It’s understood as a settling of scores at the top, which has nothing to do with the overwhelming majority of the population that this little clique has been oppressing for the longest time. That’s how people are seeing it. There is no honor among thieves. These twists and turns do not surprise us. The fact that the judge fled, that the court clerk was found dead, these kinds of things have been going on. We have had blatant assassinations, massacres against communities, and no real legal pursuit in a justice system that is so corrupt.

The only regret is that the Haitian people hoped they would be the ones to topple Moïse and actually hold him accountable for his crimes against humanity and the money he stole while in office, so we could recuperate that wealth as a people. This is despite the Haitian oligarchy and media outside of Haiti trying to pass him off as a folk hero. Of course, there are supporters of Moïse, but they are in the minority.

Regarding who exactly is behind the assassination, to quote one of the grassroots people I was speaking with, “Look, this guy eats from so many different troughs, that when he gets food poisoning, you know, it’s hard to say from which one.” There are public accusations, made by several people, including a former senator, that Moïse was very involved in the drug-trafficking trade. They have even been saying for several years that he had an airstrip on his banana plantation. So that is one possible connection. Another is that Moïse had been feuding recently with some members of the oligarchy, taking over their businesses and creating his own under his and his wife’s name, calling it JOMAR [a portmanteau of their first names]. And when you step on these people’s toes, they deal with you in a particular way. So, it is hard to say. Everything is possible. The point is that it was not the people storming the Bastille.

Moïse was so well protected. The grounds were all patrolled. There were snipers on top of the house. Somebody described the several roadblocks that were in place before you could get to the house—at least four. So, for people to be able to go through all of that unchallenged, and then to kill so brazenly, there is definitely something going on.

When the head of the bar association, who was Moïse’s neighbor, was assassinated, and a group of attorneys wanted to put some flowers in front of his home, they couldn’t get through the first roadblock. Now we are talking about not just ordinary people, but attorneys going to put flowers as tribute in front of the home of the slain head of the bar association. There was tear gas, bullets were flying, and it was stopped very quickly. So, people are saying: How could these guys have gotten in so easily, entered Moïse’s home, even his bedroom, and murdered him? It was a very sophisticated attack, highly planned, with very big people involved at all levels.

CV: What about the role of the United States? It is hard to believe the assassination could happen like that without any U.S. knowledge, even if they supported Moïse along the way.

PL: Yes, people in Haiti are saying that nothing like this happens without the knowledge of the United States. The United States is just so dominant and, of course, Haiti is still under occupation by the United Nations, but it is really a U.S. occupation through the United Nations. For example, according to several reports, the Colombian mercenaries you mentioned earlier had been in Haiti for months before the assassination, working with the Haitian police, and with the full knowledge of the Haitian government, Colombia, and the United States. These are not people who just happened to drop by. On top of this, around three weeks before Moïse was assassinated, a group—a so-called gang, but really one of the government-financed and -promoted death squads—took over a very rich neighborhood called Laboule, where the house of former president Préval’s widow is located. In no time, it was reported that the Colombian mercenaries had cleaned out that neighborhood. Everything together, it just does not sit well at all. This whole whodunit is like this, we know it’s them taking care of business at the top. It’s wolves fighting over the lamb, which is us, the Haitian people.

CV: And then there’s Ariel Henry, who was sworn in as the acting prime minister of Haiti, handpicked by Moïse, and fully backed by the Core Group.

PL: Precisely. It has also been reported that Henry has the support of Barbecue. Henry is not somebody who just came out of nowhere. He was part of the first coup d’état against President Aristide in 2004 and actually headed the illegally constituted group that they call the Council of the Wise—there is no such provision in the Haitian constitution for anything like this. This was a U.S.-constructed thing to try to give a veneer of legitimacy to the coup. Henry is a player within that whole group. He was also director general of the Ministry of Health and then the ministry’s chief of staff under Préval. He is no angel. Make no mistake—this is the exact same regime as that of Moise, just with a different face.

CV: Henry also worked with the United States in their atrocious response to the 2010 earthquake. Could we talk about the earthquake that just happened on August 14? Haiti was hit by a devastating 7.2 magnitude earthquake, and then by a tropical storm. Thousands of people have died, been injured, and are now homeless. Even people whose homes are still standing are sleeping in the streets for fear of the aftershocks. Hospitals have been severely damaged, and then there’s always the problem of aid never getting to the people who need it. The earthquake and the storm are natural disasters, but there are real social factors behind why the people of Haiti are so vulnerable when dealing with climate events such as these. Could you speak to this, as well as how this fits in with all the other things happening?

PL: The earthquake is another example of the devastation of Haiti. Again, when Haitians ruled Haiti, with President Aristide for example, it was the Haitian population making decisions about the tax money; the resources of the country; building schools, hospitals, clean sources of drinking water; providing for the local agriculture and food production; all those things that were going to improve people’s lives. There was also in place a protection agency for the civilian population in case of natural disasters. They were made up of young people who were extremely well trained, many with the help of Cuba, in disaster preparedness and what to do in the aftermath. There were a series of places, in various communities, where people knew how to predict climate events and prevent devastation, and could help prepare the population as needed. It was all in place. But then, with the U.S. coup, they chased all of them out, called them Lavalas, and destroyed this infrastructure that was established for the civilian population.

Now, every year, we know that we are going to have a hurricane. When Haitians were ruling Haiti, we were prepared for that. “Okay, we know it’s coming, it’s not the end of the world; where Haiti is, that is what’s bound to happen.” But there was all the equipment in place. There was infrastructure to deal with it, so people knew how and where to take shelter, what to do before, during, and after, like they do in Cuba and other places. All of that was destroyed. What we have now is that, every year in Haiti, any strong wind becomes a catastrophe. There are other countries in the region that, yes, are affected by this kind of climate (they are natural disasters after all), but it’s always much, much, much worse in Haiti, because of the lack of preparedness, the population being so exposed, and nothing in place for how to deal with the aftermath. This has been consistent since the coup of 2004.

MP: I have been increasingly concerned about where the relief money is going, just as with the 2010 earthquake, when, as we talked about, you had the major NGOs like the Red Cross raising all this money that never reached the people who needed it. This time around, people are much more aware, and I think there are people who genuinely want to avoid that, and want to make sure that the resources and money directly benefit the Haitian people affected. However, some of the left progressive organizations in the United States, even some of the militant Black organizations, are circulating lists of organizations that people should donate to. And some of the organizations on the different lists are problematic.

They are people who can talk a good talk on the international front, have this kind of militant rhetoric, but on the ground, it’s another story. Many of them are ambitious politically, meaning they want to run for office and are cutting various deals, and some were even involved in the coup against President Aristide. I worry that they are using the goodwill of people who want to donate to Haiti, in order to collect money basically to build up their own organizations. Many of these organizations are against the mass movement on the ground in Haiti, they are against Lavalas. One just has to be careful.

When people ask me where to donate, I tell them that the only organization I trust, given the situation on the ground, is the Haiti Emergency Relief Fund, which gives everything they collect to the Haitian people. I know sometimes people want these extensive lists, but if you do that, you really do have to vet them, you have to know who is who, who is doing what where. There are some organizations, for example, that really don’t even do relief work but are putting out calls for donations anyway. I mentioned this already, but I am referring to this as the solidarity industrial complex, a kind of imperialist type of solidarity. There’s a real danger of people who genuinely want to help, but who don’t really know the situation on the ground, and rather than talking to various people, trying to get a sense of who is who, trying to be accountable, they quickly make these lists and pronounce that they are fundraising for Haiti. Well, it often ends up a smaller version of what the large NGOs are doing with the aid, and they end up undermining the mass movement on the ground. I tell them, you know, all of us are responsible for the points of references we choose. Wilmette Brown, who cofounded Black Women for Wages for Housework, said that, and I absolutely believe it. It was one of the many brilliant things she said.

Somebody contacted me about donations, and said something like, “Oh, I was thinking of donating to such and such group, but then I found out that they’re not Black-led.” Their criteria for donations is that a group be Black-led. Excuse me, the Duvaliers were Black, Moïse was Black, Barbecue is Black! That can’t be the only criteria for who you listen to as your point of reference. When you’re living in the belly of the beast and dealing with structural and other forms of racism on a day-to-day basis, there can be a tendency to go in that direction, which is a little bit separatist, to say, “Well, I’m going to relate to the Black organizations.” I absolutely believe in autonomy. I mean, I helped found Black Women for Wages for Housework! But it just can’t be the only criteria. I grew up in Barbados, which is around 95 percent Black, and everyone knew that the enemy can have a Black face, it’s very clear. I think it is something that we, who come from predominantly Black societies, have to keep reminding people in the United States, Europe, Western nations more generally, that just because somebody is Black and they talk a good talk doesn’t mean you can bypass accountability and be exempt from trying to find out more about that person or organization.

CV: To close, I just want to touch on the future. What is in store, what is the hope?

PL: The people of Haiti will continue to mobilize. They are not giving up on their hopes and their dreams. They are not giving up on the plan, which is investir dans l’humain, to invest in people; the plan that was being implemented by Lavalas. To use the resources of the country, to use the tax money that the Haitian people contribute to the national treasury, so as to actually benefit the majority population; to build schools, hospitals, clean sources of drinking water; to improve the working conditions, so that our peasantry and every single person in Haiti can live with dignity in a safe and flourishing environment. Not only that, but also fun activities for the people! To take our country back from all those death squads imposing a reign of terror on the population.

Because of the death squads, whether you are in the city or in the country, you often have to flee or take your chances with the sharks. If you are a farmer and stay, you lose your land, and then on top of that are forced to come back and work on that land, practically unpaid, for the very people who took it. The land grabs, which are violations of the rule of law, are not happening by chance. It’s part of a policy that has been implemented under the nearly eighteen-year occupation, decided on at a meeting in Ottawa, Canada, in early 2003.

The people of Haiti are saying, “No, we are going to fight, we are going to put a stop to this, and we are going to overturn and change that system.”

CV: I also want to add that, as we well know, the United States keeps deporting Haitians, keeps occupying Haiti, and non-Haitians in the United States have a responsibility to mobilize here, at the heart of empire, against U.S. imperialism and in solidarity with Haiti and the Haitian people. As Margaret has said, we owe a great debt to the Black Jacobins, not only of 1804, but also of today.

PL: Thank you for saying that, I agree with you wholeheartedly. The Biden administration knows very well what’s going on. That is why Haitians will tell you that it’s the laboratory at work, referring to the entire system. What they mean is that there is nothing that goes on in Haiti without the knowledge of those who control the aid, the Core Group, or the “Core Gang” as Haitians call them. That is not to say that they are omnipotent or what have you, but they have such penetration in the country that anything harmful for the people of Haiti is part of the policy they are implementing. Our task is to overturn that, and this is an appeal for solidarity, as you said. We Haitians are very familiar with everything that has been happening. But to an outside audience, they may think that we are making it up, or exaggerating. We are not. Everything has been documented and recorded, and it is very clear. We need to let the world community know, and we hope that people struggle with us in solidarity.

Pierre Labossiere is cofounder of the Haiti Action Committee and is on the board of the Haiti Emergency Relief Fund. Margaret Prescod is part of the Haiti working group of the Global Women’s Strike and cofounder of Black Women for Wages for Housework. She is the host of “Sojourner Truth,” on Pacifica Radio, which regularly covers Haiti. Camila Valle is an editor, translator, and writer in New York. She is assistant editor of Monthly Review.

They would like to thank Selma James for helping to coordinate the interview.

Subscribe to Monthly Review ($39/year)

Spread the word