Phyllis Ford-France didn’t know what to expect when the doors opened at Chicago’s Michele Clark High, on August 30th, but she was feeling anxious. For eighteen months, she had been teaching mostly into a pixelated void. “They were not really online. They just turned on their avatars, and they would go away,” she said. But, when the students arrived, they couldn’t get enough of her. Now, several times a day, just before the bell rings to start class, a gaggle gathers outside Room 130, where Ford-France, the ninth-grade history teacher, smiles and returns their energetic hugs. As current students press through the doorway to take their seats, they often find one or two of their predecessors sitting at desks near the back of the room, waiting to see when the teacher will spot them and shoo them, laughing, into the hall.

In the first days of the school year, Ford-France mixed brainteasers and getting-to-know-you games with messages designed to show that she recognizes what the students have endured. She also asked each of the ninth graders to write an autobiography. “I want to know everything about you,” she said. “Your first kiss. Your first edible. Your first drink.” What she got back rattled her, even after eighteen years at Michele Clark. “A brother getting killed or a father getting killed, or a mom and dad in jail, or how they use substances to cope,” she told me. “What truly is mind-boggling is that, in spite of their challenges, they’re still coming to school.”

Michele Clark High, built nearly fifty years ago as a middle school, is in Austin, on Chicago’s far West Side, about six miles from downtown. Named for a CBS News correspondent who died young, it enrolled about five hundred and twenty-five students this year, ninety-eight per cent of whom identify as Black. The school’s approach has long been to support first, then teach, but, once the pandemic took hold, the students’ needs ran deeper. Black Chicagoans died of covid at more than twice the rate of white residents. Unemployment rose in neighborhoods that already had some of the highest jobless rates in the city, leaving more families without enough food to eat or space for children to study. And then there was the strain of startling new levels of gun violence. Attendance at remote and hybrid school was sporadic. “A lot of what they were supposed to learn, they didn’t learn. In fact, they regressed,” Ford-France said. Donovan Robinson, the director of students, told a group of Ford-France’s students, “covid cheated you all out of junior high school. We want to make sure that you gain back all that you lost.”

Michele Clark’s principal for the past six years, Charles Anderson, is a former teacher and school counsellor who revels in the unorthodox. On the first morning back at school, Anderson orchestrated an outdoor welcome. Dressed in a pale-blue cotton suit with short pants and unlaced high-top sneakers, his long locs spilling from beneath a striped porkpie hat, he danced onstage as a d.j. spun records. Chicago politicians spoke, as did a pastor and several students. “We want to start the school year off different,” Anderson called out. “All the other schools that ain’t got cool principals, they probably went right to a class.” Afterward, Anderson worked the hallways, and mingled and joked with students during lunch period. He traded his suit jacket for a black T-shirt inked with an image of a theatre marquee. The words read “Michele Clark Presents Live & In-Person Learning.”

Principal Charles Anderson stands at the school’s entrance.

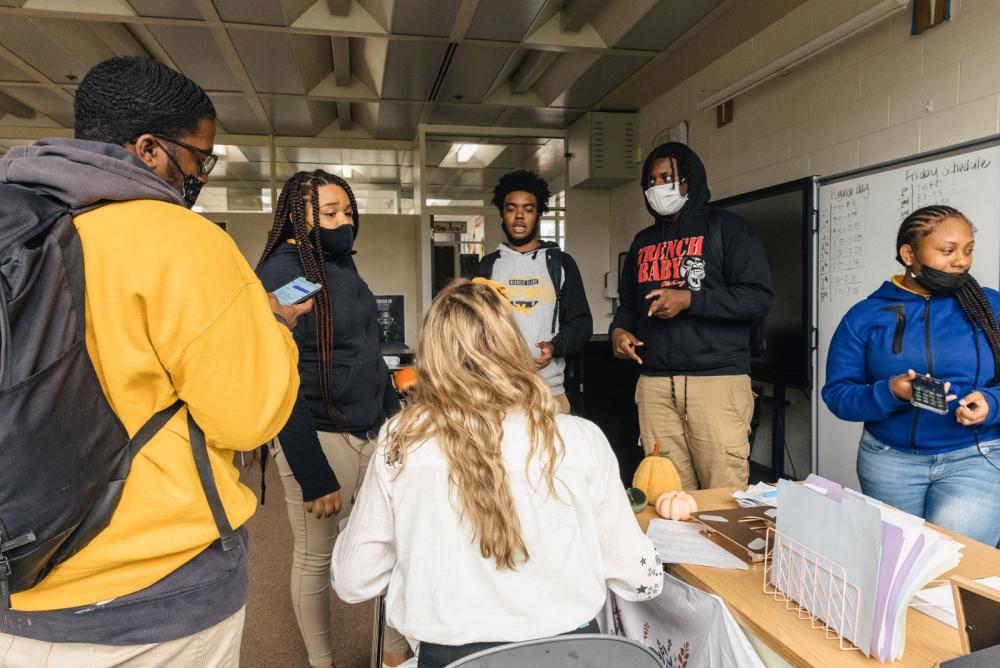

Donald Polo, an English teacher, talks with students between classes.

Donald Polo, a ninth-grade English teacher whose dynamic back-and-forth with students resembles an improv show, said that conducting his classes online was “gut-wrenching.” Unable to share his customary fist bumps and heart-to-heart conversations with students, he felt painfully aware of what they were missing. It turns out they did, too. “This has been the first group of students I’ve had in a long time where they’re just really happy to be back in school,” he told me. The ebullient Polo also loved being back in action. One day, as an icebreaker, he asked each student to say their birthday and matched the dates to a zodiac chart with a list of accompanying attributes. “What about pessimistic? Do you know what ‘pessimistic’ means?” he asked one student. “Not at all,” she replied. It wasn’t long before he projected a favorite quote on the screen, “Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken.”

When I asked Ford-France what she hopes students will learn this year as Chicago emerges from the pandemic, she said “resilience.” Anna Taglia, the assistant principal, said “perseverance.” covid is only part of it. Citywide, more than three thousand people have been shot, and six hundred and thirty-two killed, this year alone. At least one hundred and sixty-two children younger than sixteen have been shot, including at least fourteen younger than age six, according to the Chicago Sun-Times. I was in Abby Burridge’s English class shortly after noon on September 22nd, when students’ phones began lighting up with warnings that someone was planning to shoot up the school. The day before, two fifteen-year-old Simeon Career Academy students had been murdered in separate shootings on the South Side, making the threat seem all too real. “Anderson sent an e-mail to the faculty,” Burridge told the students. “There is no threat to our school.” That didn’t stop dozens of parents from racing to collect their children, causing a traffic tie-up outside. Conray Jones, a Chicago police officer who has a full-time assignment at the school, felt sure that it was a false threat, but he still donned his ballistic vest and called in reinforcements to help manage the exodus.

Ribbons outside the school honor community members who died by gun violence.

Conray Jones has a full-time assignment at Michele Clark.

I spent fifty minutes one day talking with Burridge’s students, all seniors. The pandemic was bad, they agreed—the lack of contact, the feeling of being cooped up—but the violence on the West Side worsened their problems. Tajiuna Cooper, known to her friends as Strawberry, was the captain of the girls’ basketball team before the pandemic. When Michele Clark closed last year, team practices ended and she was scared to exercise in her neighborhood. Her skills faded, and she quit. “I lost my hope in basketball,” she said. When I asked what time she would go home from school if the choice were hers, she said, “Never go home. Have a kitchen here. Shower here.” The students laughed, but others echoed her message: Matthew Davis, a football player who aims to attend college anywhere but Chicago, said, “I get nervous, like, every day when I wake up. I just pray that I just make it home.” For reasons that he did not feel comfortable sharing, his mother drives him to and from school. As Davis finished, Elijah Adams called out from across the room, “Rule No. 1!” What’s that? I asked. “To make it home,” Adams said.

Adams, whose goal is to make the honor roll, reach college, and become a psychotherapist, said that he learned to watch his back during the pandemic, when he was home in his neighborhood all day: “It’s overwhelming at some point when you’re around that, and you realize that it could actually be you. And you just think school really saved you—it kept you out of the way of most harm that the world brings.” For Adams, Michele Clark is “the home that welcomes you with whatever you bring. It’s, like, even if you don’t have that person at home that will give you encouragement, or will give you the valuable life skills that you’re looking for, the school will give it to you.” Johnny Matthews, a police dispatcher and the father of a Michele Clark junior, serves on a council that helps make policy for the school. He told me that he sees Michele Clark as a “safe haven” for students. “You have people who really care about you.”

Abby Burridge, an English teacher, speaks with students during class.

To that end, Anderson spends countless hours rustling up partnerships with community groups and benefactors. A grant from Chance the Rapper funded a slick audio studio. An organization called build is helping with gardening lessons and a chicken coop. The school won a competition to receive a fully outfitted weight room, replacing dangerously worn-out donated equipment. To motivate the many students who aim for college, Anderson wants to award six annual scholarships of a thousand dollars each. “He stays up at night thinking of ways to reach students, ‘How can this be a place they want to be?’ Because they need a place,” Carole Campbell, a retired teacher who works with parents and informally counsels students, said.

Campbell works one floor down from Burridge’s classroom, at Parent University, a citywide program that helps solve the problems of students’ parents and guardians, from a lack of food and a shortage of laptops to eviction notices. Recently, the staff has been helping families write obituaries. One day in September, a thin boy walked into the office of Pamela Price, who directs the program at Michele Clark and across the city. His sibling had just been shot and killed. As the boy struggled to sort things out, she let him know that she was listening and asked how she could help. A few days later, he returned to her office and told Price that he was looking ahead. His sibling “would want me to keep on,” he said. “I’ve got to do good.”

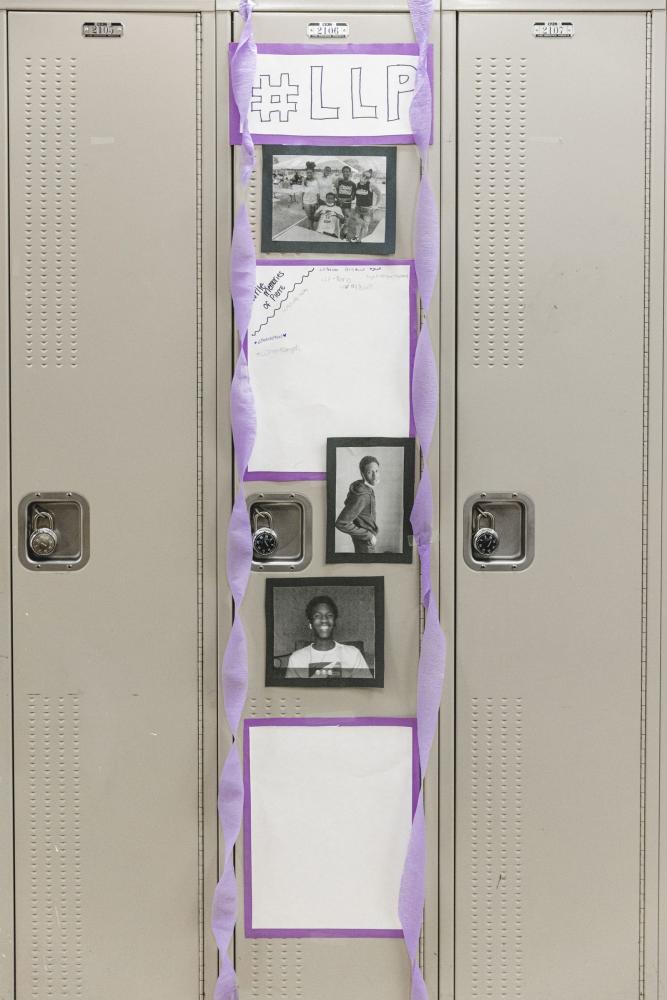

The locker of a student who was killed in September has become a memorial to him.

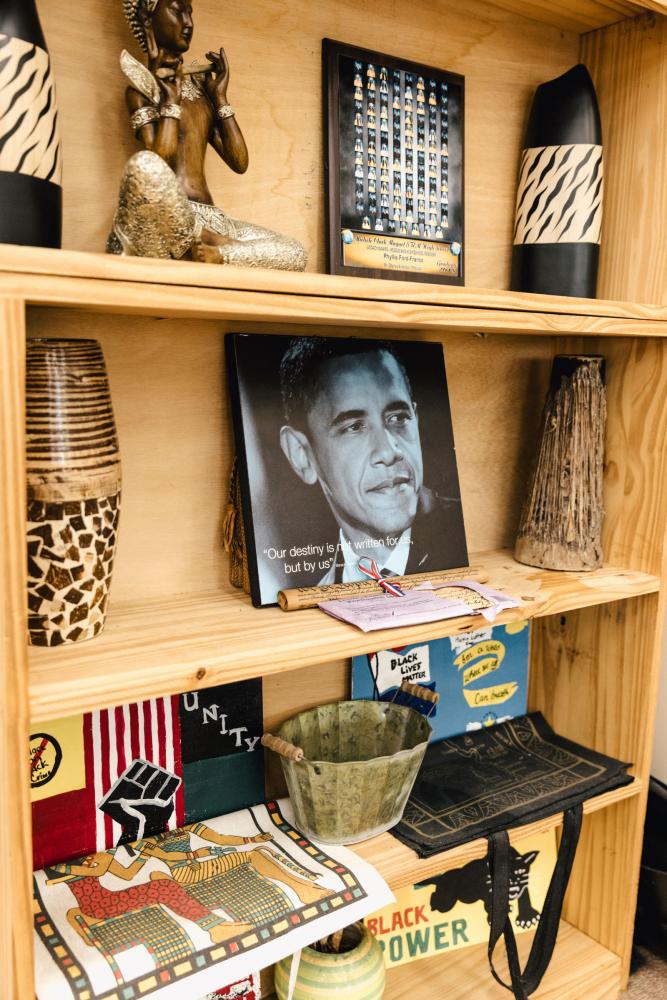

A shelf in Phyllis Ford-France’s history classroom features antiques and memorabilia.

Less than a week later, two Michele Clark students were shot, in separate incidents. One died. As word spread through the school, Anderson gathered his staff to consider what message to share with teachers and students. They decided to give students a moment to reflect and to assure them that faculty and staff would be available for conversations. From there, Anderson walked across the hall to the school auditorium, where a meeting of West Side parents, on another topic, was getting started. “This has been a whirlwind of just everything,” he told them. He suggested that the parents ask themselves a question: “How do I help support the students with all that is going on?”

Last Friday, shortly after sunrise, Burridge was in her classroom, getting ready for school, when several students walked in, crying. Another student, Kierra Moore, a sixteen-year-old junior, had been fatally shot the night before. Burridge told me that Moore was a “good student, a really good kid. She was always smiling, always there for everyone. It was shocking that it would be her.” At Michele Clark, teachers and staff embraced students throughout the day, in scenes tragic and beautiful. Burridge said, “Until you experience it, until you can be in a place that is so bonded by the positive, and so bonded by survival, I don’t think you feel love like this and pain like this.”

Peter Slevin is a contributing writer for The New Yorker, based in Chicago and focussing on politics. He has written recently about the meanings and political uses of socialism, the battle for Wisconsin’s electoral votes, the Trump Administration’s revival of the federal death penalty, and frustrations in Chicago with President Trump’s response to COVID-19. He spent a decade on the Washington Post’s national staff, as well as seven years as the Miami Herald’s European correspondent. Slevin is the author of “Michelle Obama: A Life,” which was a finalist for the 2016 pen/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography. He teaches at Northwestern University, where he is a professor at the Medill School of Journalism.

The New Yorker. Subscribe for $1 a week, plus get a free tote. Cancel anytime.

Spread the word