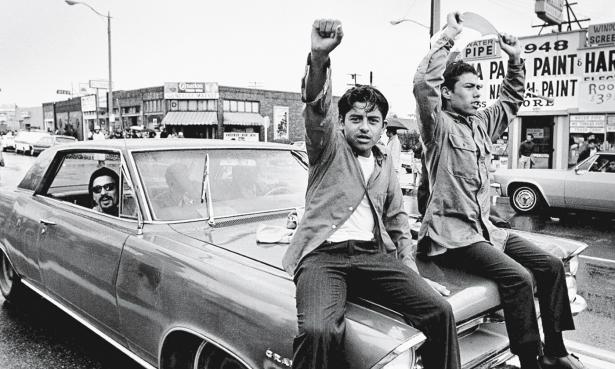

Carlos Montes is a longtime human rights activist in the Chicano community of Los Angeles. As a member of the Brown Berets, he was one of the original participants of the 1970 Chicano Moratorium, when tens of thousands marched against war and racism in East Los Angeles. Today, Montes is active with the group Centro CSO, which organizes in the Boyle Heights and East LA areas.

In the summer of 2021, Montes, who is now in his 70s, joined his younger colleague Isabel Gurrola in conversation about the Chicano Moratorium, which is marked each year with marches and other events. Gurrola is a 23-year-old organizer from South Central LA and recently graduated from California State University, Fullerton, with a degree in Chicana and Chicano Studies.

As an indication of young people like Gurrola’s influence, the annual moratorium commemoration has been rebranded as the “Chicanx Moratorium” to reflect gender inclusivity.

Montes and Gurrola spoke with YES! Racial Justice Editor Sonali Kolhatkar about how the movement for Chicanx rights has changed over the years and how it has benefited from cross-generational activism.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Sonali Kolhatkar: Carlos, what was the original Chicano Moratorium about?

Carlos Montes: The original demands of the Chicano Moratorium of Aug. 29, 1970, were to stop the war in Vietnam and also to protest the high casualty rate of young Chicano men in Vietnam. We read a study by Dr. Ralph Guzmán at UCLA that showed that Chicanos and Blacks were being put in the front lines in the gunnery crews and had high casualty rates in relation to our population. We were also against the war on the Vietnamese people.

Kolhatkar: Isabel, what does the term “Chicano” mean to you?

Isabel Gurrola: I learned different definitions of the identity Chicano/Chicana/Chicanx. I first learned that it meant Mexican American. Later, I learned that it also is a political identity where people are active in their community. They don’t take “no” for an answer. They fight for their rights, for self-determination. There are some non-Mexican American people who also identify as Chicano/Chicana/Chicanx.

Kolhatkar: How relevant are the demands of the Chicano Moratorium today?

Montes: The conditions facing Blacks, Asians, Chicanos, Central Americans, and others in the U.S. oppression. There are high incarceration rates. Look at the prisons filled with Blacks and Latinos. Look at the police killings, the dropout rates, the income inequality.

On the flip side, we are also forced into joining the military. People call it the “poverty draft.” East LA had, for many years, the largest military recruitment center, which was in Boyle Heights, and we continue to protest it. The Marines and the Army target our local high schools to recruit our young men and women.

We don’t have equality. We face racist, White supremacist conditions, especially during the COVID crisis right now. We continue to suffer unemployment, housing inequality, and a higher death rate due to COVID, so it’s all related.

Also, the U.S. empire invades countries abroad and creates and supports military dictatorships—most recently in Central America. This forces many families to flee the poverty and the militarization in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. So, we have this major crisis of refugees coming to the U.S. border because of the conditions that the U.S. created. All these are issues we protest today.

Kolhatkar: Isabel, I imagine the issues of poverty and militarization are particularly relevant to your generation?

Gurrola: I went to Norwalk High School, and before that, I went to Corvallis Middle School in Norwalk . Every year, we would have career day, and the military would always be there and say, “Join now and you could get free housing,” and the cops would be there recruiting us, saying, “You get discounts on this and that.” They were always targeting people of color as our school was predominantly Black and Brown folks. Campus police would also always criminalize us and get us in trouble.

I do have a couple of friends who joined the military after high school but only because they come from really, really poor families. They joined, and they came back all traumatized. They don’t recommend anyone join the military because it was horrible for them.

Kolhatkar: Carlos, what lessons have you learned from your decades as an activist that you can share with youth activists like Isabel?

Montes: The biggest lesson is that I, or we, need to listen to the people all the time, to the needs of the people, and listen to the youth. I remember myself as an angry young man. And I’m still angry! And I see the anger in the youth today and identify with it. It’s righteous anger over the conditions, the police killings, the poverty, the deportations of our families.

We have to listen to our people, our community, and learn from them because everyone has something to contribute. So, as a veteran organizer, I always listen to people, and I always ask a lot of questions, such as, “What do you think? What do you wanna do? What’s going on?” I try to understand and then use that as an organizing tool.

Kolhatkar: How do you stay engaged and not burn out? How do you avoid the pitfalls that so many movements struggle with, such as infighting?

Montes: In addition to staying in the community and listening to the community, stay healthy! And don’t eat junk food. Don’t burn out, always be mindful of your body, your mind, and your health and your community’s health. When you’re stressed out, don’t go toward drugs or alcohol.

I’m proud to say I do yoga! And I gave up carnitas and red meat 25 years ago. My community laughs at me, saying, “C’mon, Carlos, how can you be a Chicano and not eat carnitas?” That junk food will kill you! We’ve got something like five McDonald’s in Boyle Heights, and they’re always packed with our people, and I just go in there to socialize.

Sometimes, we go into meetings and there’s struggles and fights, people disagree. And I just remind myself that we’re all fighting for equality, we’re all fighting to have a successful march and rally. These differences, we can work them out. Let’s listen to each other and not cut each other off, and work for unity. I think we all need to be in it for the long haul for our freedom, our liberation.

Gurrola: People like Carlos inspire me because 50 years later he’s still fighting, so we need to all keep fighting. But you do need to take mental health breaks because it does lead to burnout. Luckily, I have not experienced burnout, and people like Carlos keep me going and keep me wanting to fight for change. I actually do yoga too, at my house with my grandma!

Kolhatkar: Isabel, how have young people like yourself expanded the vision of the original Chicano Moratorium? What are the issues your generation fights for today that were not part of the original movement?

Gurrola: These days, there is greater inclusion of the LGBTQI community. Fifty or so years ago, it was more focused on racial oppression, and now it’s more intersectional. As Carlos was saying, Black folks, Asian folks, we all come together through unity and support each other. Despite having small disagreements and arguments, we still come together and fight against our common oppression, which is White supremacy, and fight for power and control.

A lot of youth are fighting for ethnic studies programs in K-12 schools. I never took an ethnic studies class in my high school because it was not available. It wasn’t until I took such a class in college that I learned a lot about my history, about gentrification, imperialism, and White supremacy in general. I would come back from college, and whatever I was learning, I would see it in my community.

Kolhatkar: How do both of you keep your community centered in your activism?

Montes: The thing that we all have in common is that we’re all oppressed as a people. And we’re all working people, we all work for a living. When you do community organizing, at meetings you’ll see families with moms and kids, the young and the old together, and we have the gay community there too, and it’s beautiful to see us marching together. Just to quote the old cliches, “Sí, se puede,” and “Don’t mourn, organize!” and “The struggle continues.”

Gurrola: Solidarity and unity are very important, and as Carlos was saying, “Always listen.” And give space to those who are more oppressed than us.

Kolhatkar: Carlos, what inspires you about youth activists like Isabel?

Montes: I admire the new generation of activists, especially the massive demonstrations last year due to the George Floyd killing. It was a rebellion that was multigenerational, multiracial: Asian, Chicano, Latino, White, Black, marching together. I was out there, but I got a little tired and couldn’t go every day. And what I saw last year at the Chicano Moratorium’s 50th anniversary was a whole new generation of high school, college-aged, and unemployed youth that just came out and said, “I’m not Latinx, I’m not Hispanic. Yes, I’m Chicano!

Spread the word