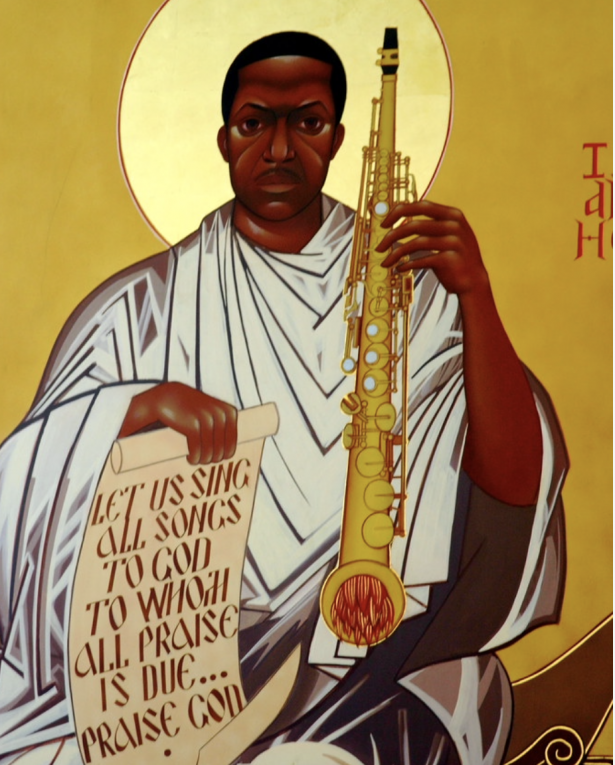

THE SAINT JOHN Coltrane Church in San Francisco — a branch of the African Orthodox Church, where the jazz musician John Coltrane is the canonized patron saint — is a family affair. It was founded in 1969 by His Eminence Archbishop Franzo W. King, D.D., and his wife, the Most Rev. Supreme Mother Marina King, before they possessed such lofty titles. (Their daughter, the Rev. Chaplain Wanika Stephens, Archpriest, M.A., is also a pastor there.) The church began around 1964, as the Jazz Club in the couple’s garage — “a listening clinic,” F.W. King, now 77, says on a recent Zoom call with his wife, 75, from their home in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point. (Their daughter, 57, also joined.) “Maybe less than a dozen brothers and sisters would come together every week. Everybody would bring a new album. We’d put the music on and start testing our ears and our knowledge,” seeing if they could name the drummer or the piano player on a track without looking at the record sleeve. One day, someone brought Coltrane’s 1965 record “A Love Supreme,” and King looked at the liner notes, which Coltrane wrote himself. “All Praise be to God to whom all praise is due,” Coltrane begins, and then tells a story: “During the year 1957,” he writes, “I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music.” In those years, Coltrane was addicted to heroin and — so the legend goes — while experiencing withdrawals heard the voice of God and got clean, rededicating his life to music.

“I wasn’t really that impressed!” King says. “I didn’t even want to listen to the album.” His own father had been a Pentecostal minister, and King believed back then that he had “successfully escaped from the raft of the church.” This changed a few months later, when he and his wife attended a Coltrane concert at the Jazz Workshop, in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood, to celebrate their first wedding anniversary; the doorman was a friend and sat the couple right in front of the stage. “So we were able to get a full dose,” King says. There have been countless attempts to capture the power of Coltrane’s music — his unmatched ear for both melody and chaos, his seemingly endless ability to find new sounds in traditional chords, the complex interplay between him and his band (which, in addition to Coltrane on saxophone, included Jimmy Garrison on bass, Elvin Jones on drums and McCoy Tyner on piano) — but, to King, “It was as though he was speaking in tongues and there was fire coming from heaven — a sound baptism,” he says. “That began the evolutionary, transitional process of us becoming truly born-again believers in that anointed sound that leaped down from the tone of heaven out of the very mind of God, stepped from the very wall of creation and took on a gob of flesh, and we beheld his beauty as one that was called John.”

There is a long and rich tradition of popular music fans deifying their icons. A famous, if dubious, graffiti tag in mid-60s London consecrated the then-lead guitarist for the Yardbirds, proclaiming, “ Clapton is God.” The mythology surrounding the blues singer and guitarist Robert Johnson claims he sold his soul to the devil sometime in the 1930s in order to gain mastery over his instrument. Google a certain disgraced pop star in 2021 and the algorithm might helpfully suggest the following question: “Was Michael Jackson a gift from God?” Any musician who is heralded as the second coming tends to be brought back down to earth eventually, whether through changing tastes or human foibles (Clapton is now an anti-vaccine proponent), though there was always something different about Coltrane, whose death from cancer in 1967 at age 40 transformed him into a kind of martyr. Through the years, the story of Coltrane’s veneration has been treated by his critics and biographers as a quirky footnote to his afterlife, if not ignored entirely, but it provides a revealing glimpse at his legacy, as well as a key to understanding the intensity of his appeal.

Spread the word