When the Democratic Socialists of America was invited along with new left-wing parties and movement organizations to observe the recent presidential election in Chile, I wasn’t hopeful that we’d be witnessing a victory. I was still excited to go as DSA’s representative because I partly came to socialism because of my Chilean-born father’s support of (and subsequent punishment for his participation in) the leftist Popular Unity in the early 1970s.

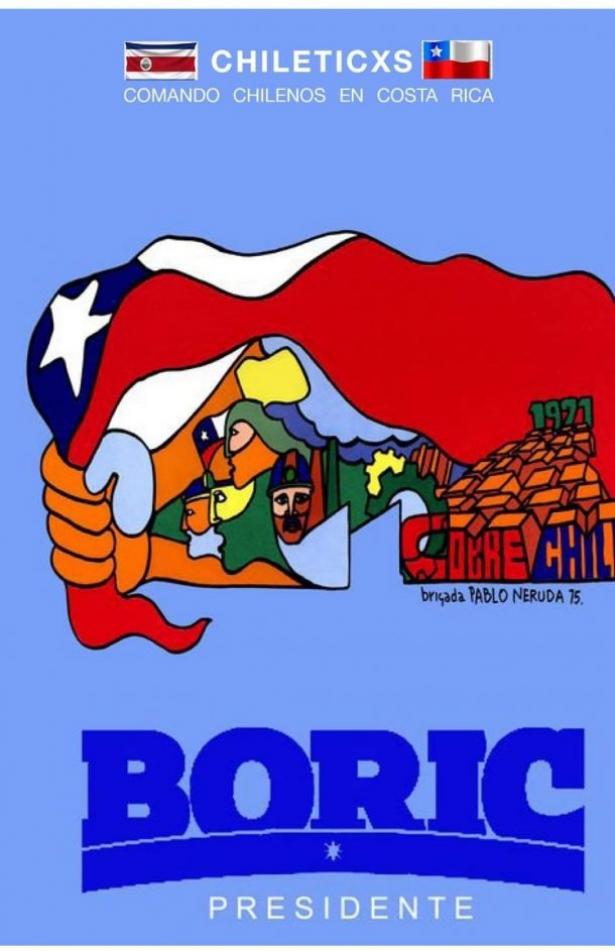

DSA’s delegation to Chile gave me a front row seat to see how the Left was able to win the election. By little over a ten-point margin, socialist Gabriel Boric of the alliance Apruebo Dignidad (Approve Dignity) defeated the far-right Republican Party’s José Antonio Kast. Boric is set to become the youngest Chilean president ever, and the most left-wing since Salvador Allende. But this trip also provided insights into how the Right is standardizing its political strategy across the globe. Potential collaboration to bring back to the states also arose out of the conversations between the Chileans and international guests.

Two parties of a coalition called Frente Amplio – Boric’s own Convergencia Social and its ally Revolución Democrática – hosted international delegates for three days before the historic election. Both parties are no older than a decade and their international guests reflected this as well. Participants such as Spain’s Podemos, Argentina’s Frente Patria Grande and Brazil’s PSOL were all formed less than twenty years ago. DSA was the only U.S. political organization to be among the global delegation. Less than a week before the election, DSA’s international committee released a statement in support of Boric’s candidacy and warned against backtracking on democratic gains to replace the constitution written under the dictator General Augusto Pinochet, whose 1973 coup against Allende and reign of terror lasted until 1990.

DSA and other guests met with Chilean coalition party leaders, Boric campaign staff, and social movement activists to observe and learn how they were prepared to defeat the right. Boric had underperformed in the first-round election in November by falling second to Kast, and leaked polls (nothing can be published two weeks before the election) showed a dead heat for the second round. On December 17, Revolución Democrática’s Giorgro Jackson, a congressman and close ally of Boric since their days as student leaders of Chile Winter, told us that the Left was concerned that Kast could attempt to undermine the election credibility as Donald Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro have done.

Chilean far-right militants were pushing for Kast supporters to discredit ballots of Boric voters. In the end, Kast declined to seek this option possibly because the margin was too wide, general faith in Chile’s election system was too strong (and was being administered by a right-wing government), and perhaps he lacked the shamelessness of his U.S. and Brazilian equivalents.

On December 18, the delegation traveled to Valparaiso, the major port city about two hours from the capital of Santiago, to meet with the eponymous region’s governor Rodrigo Mundaca and five regional mayors. Mundaca, a former engineer and member of the water-rights-defending social movement MODATIMA, hosted us at Parque Cultural, a culture center that had once been a prison and torture site. The governor was one of only three of Chile’s 16 regional heads elected in the first round. He talked to us about David Harvey and Chilean resistance to neoliberalism. After learning I was with DSA, Mundaca exclaimed “we need more democratic socialists in the US.”

David Duhalde with Valparaiso governor Rodrigo Mundaca

David Duhalde with Valparaiso governor Rodrigo Mundaca

Later that day, the foreign guests listened to a panel of five constitutional convention members. In October 2020, Chileans voted by nearly a four-to-one margin to pass a referendum to replace the current constitution; in 2021, they elected 155 delegates to draft a new constitution. The country’s current constitution is a symbol of the neoliberalism imposed by the Pinochet military regime. A new national legal framework was a central demand of the uprising of 2019 that expressed the frustration with inequality caused by decades of unregulated capitalism backed by the armed forces.

Bea Sanchez, a convention member and the 2017 Frente Amplio presidential candidate, spoke first and expressed fear that should Kast win, he could work to kill the constitutional process. The Left and independents dominate the 155-person body, so for now, there is hope that their proposed constitution will be a progressive alternative to the contemporary document. Had Kast won, he would have been unable to stop the drafting but could have used the bully pulpit of the presidency to push for a no vote in the national referendum to accept or reject the replacement.

While Kast didn’t win, panel member Barbara Sepúlveda, a Communist Party activist, reflected the long-term concern about the growing influence of the Right, including the ability to find wedge issues, such as immigration, in Chile. While traditional conservative parties have collapsed, Kast’s Republican Party represents an embrace of the authoritarianism of the Pinochet era tied with trends of right-wing populism across the world. She noted how Trump’s solution to immigration was a wall and Kast proposed digging a ditch in the Chilean desert. Sepúlveda lamented that the right wing – not the Left despite our internationalism – seems to have a global playbook.

Outside of the formal delegation, I had the opportunity to represent DSA with both the Socialist Party and trade unionists. While not in Boric’s coalition, the Socialist Party is still the largest left-wing party in Congress and supported his candidacy in the final round. In a meeting with their International and Sub-Secretaries, we discussed parallels between our countries on issues such as immigration, police reform, and changing political systems. A dinner with labor organizers included Andres Giordano, a newly elected congressman with Apruebo Dignidad. Giordano is a co-founder of the Chilean Starbucks union and expressed interest in connecting with U.S. workers organizing the global coffee chain. Coincidentally, Revolución Democrática’s new president, Margarita Portuguez ,comes out of the telecommunications union, which is an important step to bring the new left closer to organized labor.

David Duhalde at Cierre de Campaña – the formal closing of Boric’s campaign activities

David Duhalde at Cierre de Campaña – the formal closing of Boric’s campaign activities

The week leading up to the election, I was very pessimistic about Boric’s chances, given his underperformance in the first round and generally rising cynicism among Chilean voters. And the 2016 U.S. presidential election had shown me how an inevitable candidate and modern polling methods could fail. But Boric won big. The reasons I was wrong come down to at least two factors: Chileans’ commitment to the constitutional process and age demographic voting trends.

- Turnout dramatically increased, from 47% in the first round to about 56% in the second round. A major reason for the uptick was Kast’s unequivocal opposition to the new constitution. He was the only first-round presidential candidate, including conservative and moderate ones, to oppose the constitutional process. As Chileans got to know him better, the threat of losing years of work to curtail neoliberalism became more real. Research showed that the more voters were reminded about Pinochet, the less likely they were to support Kast. The death of Pinochet’s widow shortly before Election Day probably hurt Kast, too, as she evoked her husband’s regime in which she was an active participant in the minds of voters

- Kast’s social conservatism also may have driven votes against him. His alliance is the Christian Social Front, whereas Chile has recently moved to legalize gay marriage and has loosened up abortion restrictions over time. Also, youth turnout increased by nearly 10 percent between rounds. while senior turnout increased by only a few points. Exit polls showed 64 percent of young women voted, compared to about 30 percent for all genders over 70 years old. Of those women under 30, two-thirds voted for Boric. In many ways, voters were preventing reactionary politics and regression that could have reversed decades of struggle as much as for Boric’s campaign of hope.

Overall, voters prioritized preserving the path toward a new constitution over the hate-filled campaign of Kast, which focused on immigration and crime. But those two issues remain and continue to be exaggerated by the right wing to undermine progressive policies. (Without concern for consistency, Kast has now turned on the same Venezuelan migrants he once welcomed to attack Bolivarian socialism.) The first round also was when Chileans voted for the federal legislature. This lower turnout gave Chile an equally divided senate between the Left and Right, plus a congress that is majority Left but with many representatives that could be swing voters.

Therefore, Boric’s government will be a test for how new left formations can handle state power. His administration likely will bring in center-left parties and officials who have previously governed Chile. Absent a clear majority in the legislature, he may have to focus on policies he can achieve through executive order while maintaining the constitutional process. There is even a chance his term could be cut short if a constitution passes that calls for new elections. Although his tenure may likely not be as radical as his campaign rhetoric, his time in power can be a success if it helps foster a framework that Chileans can collectively use to bury neoliberalism and build a more egalitarian society.

Chileans celebrating Boric’s victory on Santiago’s Alameda

Chileans celebrating Boric’s victory on Santiago’s Alameda

David Duhalde is the former deputy director of the Democratic Socialists of America and current member of its International Committee. He formally represented DSA in Chile for their 2021 presidential elections.

Spread the word