labor Organizing the Unorganized and Union Transformation – An Interview with Jeff Hermanson

"It is in the struggle to organize the unorganized and to empower the rank and file that the US labor movement will be transformed." Jeff Hermanson

I remember hearing Jeff make this statement countless times in discussions of organizing. Hermanson brings a long and impressive bio to the labor-organizing table. He has been the director of organizing for multiple organizations: the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, the Writer’s Guild of America West, the NYC Carpenters District Council and Workers United. His organizing successes cross national boundaries, and he is now working as Organizing Director with the Solidarity Center in Mexico.

Peter Olney (PO) What does your organizing look like right now in Mexico?

Jeff Hermanson (JH) Working with Mexican unions and workers’ rights organizations, we are planning and supporting a major organizing program to transform the corporatist Mexican labor relations regime dominated by pro-company “protection unions” through organizing with existing independent and democratic unions (most of which are enterprise unions that up to now have shown little desire to organize beyond their factory walls), and by supporting the formation of new independent and democratic unions with an industrial outlook. In the few industries – petroleum, railroads, electric energy, education – where there are national industrial unions, a legacy of nationalized industries weakened by privatization, and for the most part controlled by entrenched and undemocratic leaders, we will support democratic movements within the unions.

Our aspirational model is the CIO mass organizing of the 1930s, which demonstrated the thesis that reform of a labor movement requires new organizing to break the hold of the dominant ideology – craft narrowness in the AFL of the 1930s, anti-communism, protectionism and business unionism in the US of the 1990s, corporatism, corruption, nationalism and enterprise unionism in the Mexican labor movement of today – and create a new paradigm of inclusive, militant, internationalist industrial unionism.

(PO) What about some of your experience in the USA with organizing as the road to union transformation?

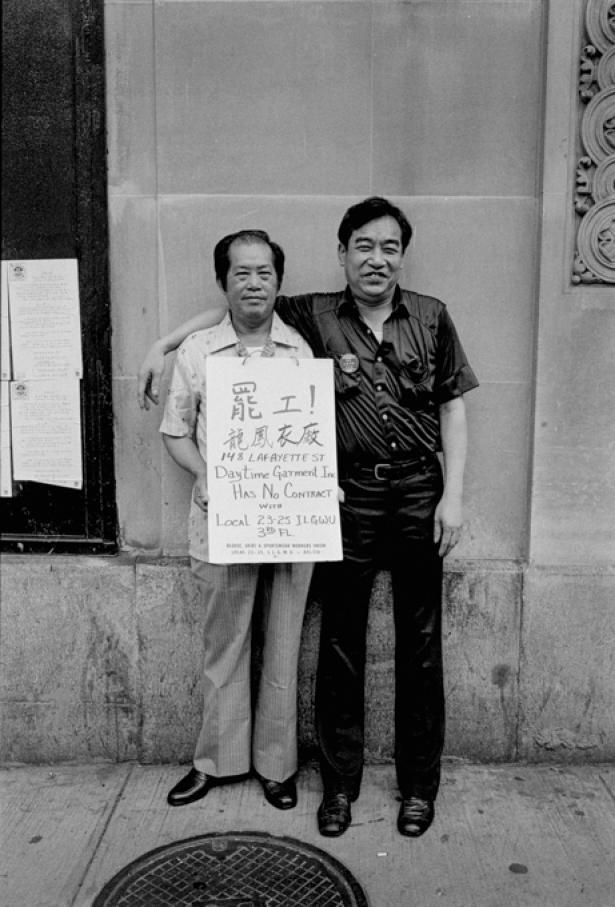

(JH) My own experience in the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) demonstrates this thesis as well, within limits: How did the ILGWU give up, or at least moderate, its protectionist “Buy American” and “Stop Imports” campaign in the 1980s and 1990s? By organizing the tens of thousands of immigrant garment workers from the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico, and Asia. Then, as the US apparel manufacturing industry passed into history, and the union’s major employers became the apparel distribution centers handling imported goods for brands and retailers, the union, now called Workers United, adopted an activist internationalism to support garment workers in other countries as part of their campaign to organize the distribution centers of firms like H&M, VF Corp., and Gap.

Again, at the Writers Guild of America West, the effort to organize reality television resulted in the election of a militant reform leadership slate, the firing of the business-oriented executive director, a former CBS executive, and his replacement by David Young, a labor radical and “blue-collar” union organizer. The subsequent WGAW campaign to organize “America’s Next Top Model” through a recognition strike, while ultimately unsuccessful, led to a strengthening of the militant leadership and was part of the build-up to the 100-day Writers’ Strike in 2007 that won jurisdiction for the union over writing for the Internet, now the principal source of employment for writers.

(PO) With your emphasis on organizing the unorganized do you mean to say that reform movements are inconsequential?

(JH) This is not to say that reform movements should be abandoned, and all efforts put into organizing the unorganized. Both aspects of struggle are essential, and reinforce each other, and sometimes one becomes the leading aspect, as in the CIO drives of the 1930s, and sometimes the other, as in the Ron Carey campaign of the 1990s that led to the militant UPS strike of 1997. Right now there is a lot of volatility in the US labor movement, with unions like the Bakery Confectionery Tobacco and Grain Millers, International Association of Machinists and United Auto Workers forced by circumstances to confront their declining bargaining power and take militant action as the employers invest billions in Mexico and close plants in the USA. This volatility can be seen in the Teamsters and United Food and Commercial Workers, now confronting Amazon in the logistics and transport sector. The victory of the O’Brien-Zuckerman Teamsters United slate in the recent election reflects this volatility and is an important step toward a more militant and member-driven approach in the Teamsters union, which will have a big impact on the upcoming UPS negotiations and in organizing in Amazon and FedEx.

(PO) One of the Teamster United slate Vice Presidents, John Palmer, was recently quoted in an article in Labor Notes:

“The organizing department needs restructuring too,” said Palmer, who worked there for years. “We waste a tremendous amount of money flying organizers around the country,” he said. “That time and resources could allow us to train people out of locals to do this. We need to have that skill on the ground everywhere; we don’t need a lot of specialists airdropped from D.C. who disappear the minute a campaign is over.”

What do you think of that statement based on your years of experience successfully organizing in many sectors?

(JH) Of course, it is good to have organizing assets on the ground everywhere, and there should be training for members out of locals; but to take on global corporations and to run national campaigns, you need a centralized campaign headquarters and “specialists” like Andy Banks and directors like Bob Muehlenkamp and John August (who ran the 1997 IBT UPS strike). You also need experienced organizers that can be sent to key locations to mount surprise attacks where they are least expected, as when the Teamsters were able to strike UPS at Paris and other European locations during that 1997 strike.

I am totally in favor of member-participatory strategies; the 2007-8 Writers Strike was totally run by the WGA members, who made all the important decisions through their executive board, composed of working writers, and through strike authorization. But they also had a strong executive director in David Young, an excellent research department, a professional communications department, and a committed staff to meet with small groups of writers, train strike captains, organize events, make sure picket signs got to the right place at the right times, and come up with effective tactics like picketing film and TV locations and shutting down the Golden Globes. It is the combination of intense member involvement and competent and experienced staff that gets the job done and done right; and with a national and international adversary, it is the combination of power on the ground in every locality where we can confront them and a strong centralized strategic direction that will win the day.

(PO) What do you make of the current strike wave, the present political landscape and what organizers should be focused on?

(JH) The current strike wave in food processing, manufacturing, health care, etc., and increasing tempo of organizing in certain sectors – digital media, higher education, and logistics – is a result of forty years of an employer offensive that depressed wages, closed union factories, busted unions and created the greatest economic and social inequality in the history of the world, with two families holding as much wealth as half the population, and with organized labor at its lowest percentage of the working population since the 1920s. The employers’ callous disregard for the lives of workers in the Covid-19 pandemic, notably in the food-processing industry and in healthcare – exposed the brutal nature of capitalist exploitation as never before; and the economic dislocation further exacerbated the declining standard of living of most working people. Pushed to the limit, large segments of the US working class rebelled against the political elites, in some cases in self-destructive political directions, in other cases by electing socialists and progressives; and in the workplaces we see a rebellion against the employer offensive, and in some cases against union leadership that hasn’t gotten the message that their members have decided it’s time to fight back with all we’ve got.

In the context of rising pressures and tensions in the economic sphere, caused by the decades-long employer offensive and the continuing decline of US capitalism, white supremacist, anti-immigrant, misogynist, anti-LGBTQ and authoritarian political ideologists, funded and supported by the corporate wing of the ruling class, have captured the Republican Party and provided an outlet for the fears and resentments of some segments of the working class and for the owners of small and medium-sized businesses. Other segments of the multi-racial, multi-national US working class have responded to the crisis of capitalism, exacerbated by the pandemic, with a fight-back against racial injustice, gender oppression, xenophobia, and anti-LGBTQ prejudice, and have supported progressive and democratic socialist candidates in local, state-wide, and national elections. I believe it is fair to say that many working people are disgusted with the current political landscape, their declining standard of living, the failure to deal effectively with the Covid-19 pandemic or the climate crisis, and the inability to chart a course forward to restore prosperity and a positive outlook for the future. Perhaps the best, and maybe the only way to turn this disgust into positive action is for the labor movement to aggressively organize at the grass-roots level and take on the corporate overlords in the workplaces and at the ballot box.

My view is that the primary, leading aspect for change in the US labor movement should be recovering the lost bargaining power through organizing the unorganized, including through cross-border campaigns in the supply chains of unionized and non-union firms alike, and through militant strike strategies that use our bargaining power to gain some control over investment decisions and to eliminate the two-tier and other contract terms that weaken our unity and our power. Those struggles can inspire the rank and file to the confidence and self-assurance that will lead to a greater role in the governance of the unions that are the basic instrument of the working class.

(PO) Thanks Jeff. Look forward to tracking your battles in Mexico!

Peter Olney is retired Organizing Director of the ILWU. He has been a labor organizer for 40 years in Massachusetts and California. He has worked for multiple unions before landing at the ILWU in 1997. For three years he was the Associate Director of the Institute for Labor and Employment at the University of California

Spread the word