When she found the advertisement for Maria, an eighth grader named E.D. was struck by the details in it. The ad was posted in a local newspaper, in 1846, by an enslaver in Tennessee. When Maria escaped, she was only 18 or 19 years old. She did not act alone. Maria ran with “a free man” named Henry Fields. For faster transport, Maria and Henry also liberated a gray mare. Maria’s enslaver suspected Henry had his free papers with him. But he was certain that Henry carried something else: a fiddle.

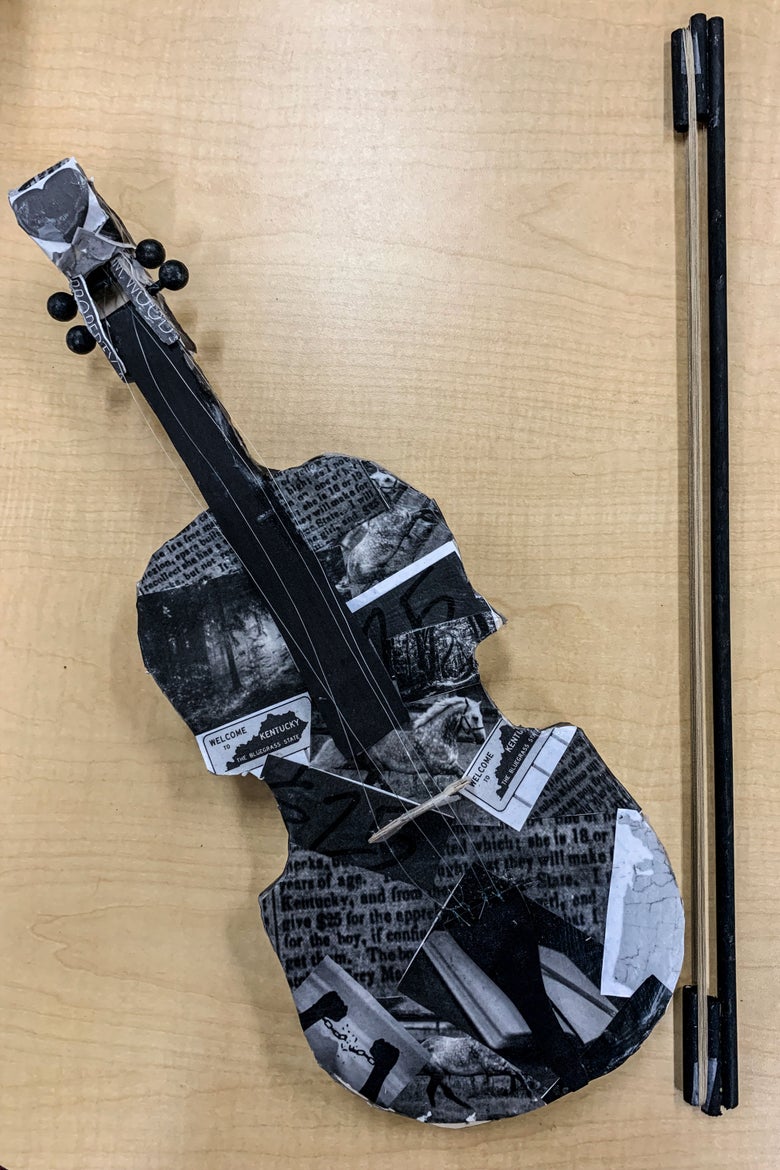

E.D.’s teachers had asked their students to respond creatively to an ad they found in Freedom on the Move, a digital collection housed at Cornell University of thousands of ads by enslavers and jailers seeking the return of self-liberating people, printed in American newspapers before emancipation. E.D. decided to make Henry’s fiddle. She made it life-size, out of cardboard and papier mâché. She covered it with a collage that tells the story of Henry and Maria’s flight. The enslaver placing the ad suspected “they will make for Kentucky and from there to a free state.” So E.D. used the image of a running horse, a “Welcome to Kentucky” sign, and a heart symbol—this last because E.D. wondered “if Maria and Henry were in love.” E.D. pasted a copy of the ad on the fiddle seven times, for the number of times the ad ran in the newspaper. It was her personal monument to Henry and Maria and their acts of resistance. “My fiddle represents Henry and Maria’s story, their fight for freedom,” E.D. explained, “but it also represents all of the thousands of other stories just like theirs, waiting to be told.” She carried the fiddle to school in a violin case.

Project by eighth grade student at Olentangy Orange Middle School in Lewis Center, Ohio. Photo by Kristin Marconi and Christine Snivley

E.D. and her teachers, Kristin Marconi and Christine Snivley, who teach middle school students in Ohio, were part of a virtual learning community created for Freedom on the Move by the Hard History Project. The goal of these workshops was to tap the genius of teachers to build a bridge between the digital archive and K–12 classrooms. As a crowdsourced archive, FOTM was built with the public in mind. Still, it takes the expertise of teachers to reach, arguably, FOTM’s most important readership: young people.

We are in a cultural moment in which teaching about racism and the world it has made is both essential and controversial. Critics rallying under the banner of “anti-CRT” describe this teaching as divisive and disturbing. But we can’t teach the history of the United States without teaching about slavery. And of course, they’re right about the emotions involved—there’s nothing comfortable about slavery. But they’re missing something: There’s a lot of good, and even joy, to be had in talking about the relentless and omnipresent resistance to slavery that we see again and again in newspapers before the Civil War, in ads seeking the return of self-liberating people.

When it is complete, FOTM will contain upward of 100,000 ads. Even though the stories they convey were written by enslavers and jailers, thousands of self-liberating people forced those stories into the historical record. Because they sought freedom, we can glimpse their personal histories, skills, languages, family ties, community networks, sometimes even their fashion sense. The Hard History Project and FOTM have been working with teachers from around the country to create lesson plans and assignments that ask students to explore the vast archive of freedom seekers for themselves.

When asked about the difficulties of teaching slavery in the current political climate, Ahmariah Jackson, who teaches English in majority-Black classrooms in Atlanta, is clear about why FOTM’s focus on Black resistance matters, both at the level of the individual and as a mass movement. “We’re speaking about the humanity of those who were enslaved, and that takes priority more than anything,” Jackson says. “I can’t tell someone what to think about their great-great-great-great-grandfather. I’m not here for that. But I’m also not here to tell a student that their great-great-grandfather was evil. I am more concerned with shedding light on the institution, the practices of the institution, and the implications of that. How are we going to shape this world, move forward, if we’re not learning from that past?” Freedom on the Move, Jackson says, “allows for a full-circle discussion. It allows for an opportunity to heal.”

Using FOTM, educators can let students’ curiosity drive the conversation about the past. Jackson recalls one student who read an ad for a man named Peter and asked: “Well, why did he have this stutter?” Her question, for Jackson, was a revelation. “We’re no longer talking about something that was in a two-dimensional black-and-white ad. We’re referring to a person by their name, by their spirit, by their existence. If all men are created equal, then it means that what we’re talking about is what exists within ourselves, what is indelible.”

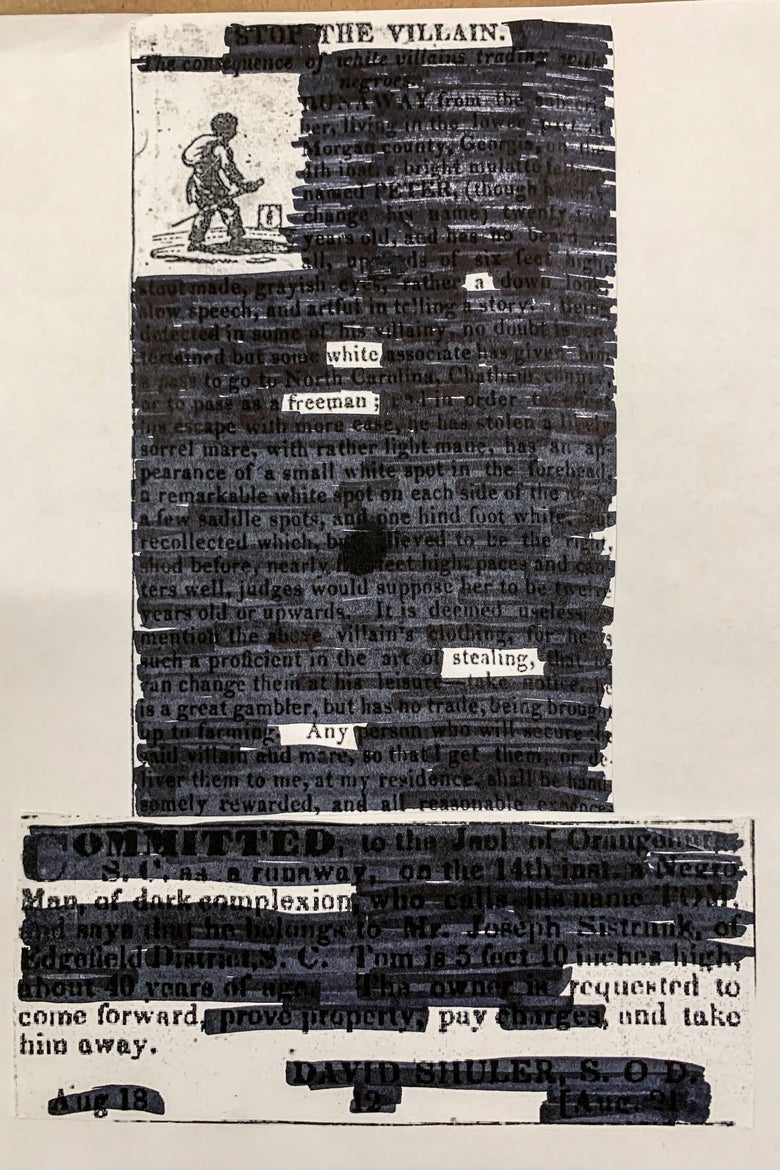

Jackson’s students decided to make a resistance newspaper called the Lion’s Side based on the African proverb “Until the lion tells his side of the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.” As Jackson told his students: “In this sense, those enslaved individuals are the lion and their stories are not and have not been told. Your charge, your challenge, is to creatively write their story.” Instead of rewards for the recapture of freedom seekers, his students repurposed the details of the ads and offered rewards to those who helped them escape. They flipped the script. This is especially important for Black students, Jackson says, because it “allows for African Americans to see themselves not just as a product of slavery, not just as disenfranchised, not as downtrodden, not as powerless, but as resolved, as survivors, and that’s important to me.”

Project by eighth grade student at Olentangy Orange Middle School in Lewis Center, Ohio. Photo by Kristin Marconi and Christine Snivley

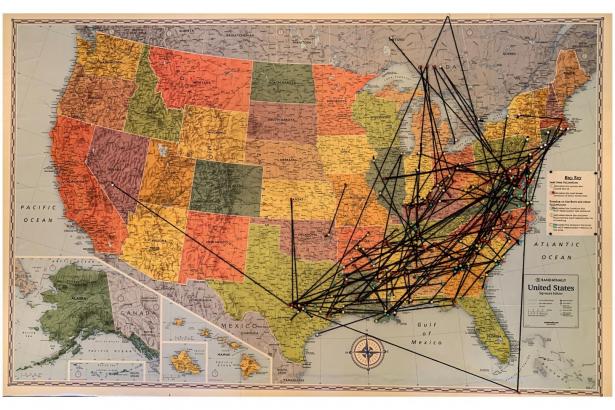

Because of the detailed nature of the ads and the large volume of them, students can see both individual stories and the aggregated efforts of tens of thousands of resisters. Consider for a moment the familiar pastel-colored maps printed in standard social studies textbooks. They might visualize the westward spread of the railroad, or crops produced by region, or even the shifting boundaries of legal slavery before the Civil War. But mapping the acts of self-liberating people in the aggregate offers a different, bird’s-eye view. Students in Marconi and Snivley’s eighth grade social studies class decided to map for themselves the suspected trajectories of individual freedom-seeking people. The collaborative assignment became part geography lesson, part data mining, part spatial reimagining. The result is a visualization of the paths of hundreds of freedom seekers, with string and brightly colored push pins. In tracing those paths, the students created a map that counters the familiar black arrows of the trans-Atlantic triangle trade and the domestic slave trade.

Other students of Marconi and Snivley had the option of creating blackout poems. They chose a group of ads and blacked out most of the text, choosing which words to leave visible. Those words, strung together, create poems.

“MY BOY PETER—Miss him—We will—no doubt—be together—again.”

“I—loved—her—but—that—white man—took—her—from—me.”

“THE VILLAIN.—A—white—freeman;—stealing—any—man of dark complexion—

requested to—come forward—pay—and take him away.”

“Maybe—this—life—can—be—different—if—I—were—on—the—other—side.”

“A—beautiful—sight—one of—smooth—and—shining—waters,

—clear—as—glass—extraordinary—blue—what—a view.”

These young writers manage to convey tragedy, fortitude, and hope at the same time. When students break down the language of enslavers and reconfigure it, or when they make their own visualizations, like the yarn map, they gain a deep understanding of the harm slavery caused to individuals and families and the collective determination of enslaved people to resist it.

When Cora Davis’ sixth grade class studied the Fugitive Slave Act, a boy named Sean constructed his own imagined narrative, in the voice of a freedom seeker:

The year is 1856. I’m waiting for my enslaver to select me. This is all part of my plan. They caught me once but they won’t do it again. The day an enslaved person gets bought they go straight to work. So, my dear diary, my plan is very simple. The Fugitive Slave Act has caused the Underground Railroad to be a hotspot of enslavers raiding and looking out for enslaved people trying to escape. What if.. what if… I could use the farming materials my enslaver gave me, which is a shovel and hoe, and dig a tunnel little enough to crawl through it?

Sean concluded his narrative: “But now I have no choice to run for it. Now I am running.”

A female student in Heather Ingram’s class tied her own imagined narrative to an ad she found for a teenage girl, like herself:

I couldn’t live my life like this. I had the spirit of my father who had ran almost three times and was never seen again. Me and my momma always hoped that he made it to freedom but we never knew. And when she was sold off, I didn’t want to live this life anymore. I’d rather be dead than be a slave another night. So I spoke in a hushed whisper: “please take me with you. I’m ready to run. I’m ready to run. I’m ready to be free.”

It’s not easy to make historians cry, particularly those who have devoted their professional lives to studying chattel slavery. Yet we FOTM historians, with many decades of archival research between us, could not hold it together when we saw the students’ projects for the first time. Echoing Ahmariah Jackson’s revelation, we, too, felt like our years of work reached a pinnacle. Like E.D.’s fiddle, what these kids have done with the archives will make you cry. But they should be hopeful tears.

This K–12 project was made possible with funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission.

Mary Niall Mitchell is Ethel & Herman L. Midlo Endowed Chair at the University of New Orleans and one of five lead historians for Freedom on the Move.

Kate Shuster is founding director of the Hard History Project.

Spread the word