A few days after the March 10, 1952 coup in Cuba, the young attorney Fidel Castro, "with a law office at Tejadillo, No. 57," filed a complaint in court charging Fulgencio Batista with the crime of sedition. Motivated by personal interest or cowardice, the legal team of jurists, defending Batista's coup against the 1940 Constitution, alleged that his actions did not constitute a coup, but rather a revolution, which was acceptable under the law.

To this, Fidel would respond in his arguments: "...There was no revolutionary program, no revolutionary theory, no revolutionary statements preceding the coup: (they are) politicians without people, who, in any case, became assailants seizing power. Without a new conception of the state, of society and the legal system, based on profound historical and philosophical principles, there can be no revolution deserving of the right. They cannot even be called political delinquents."

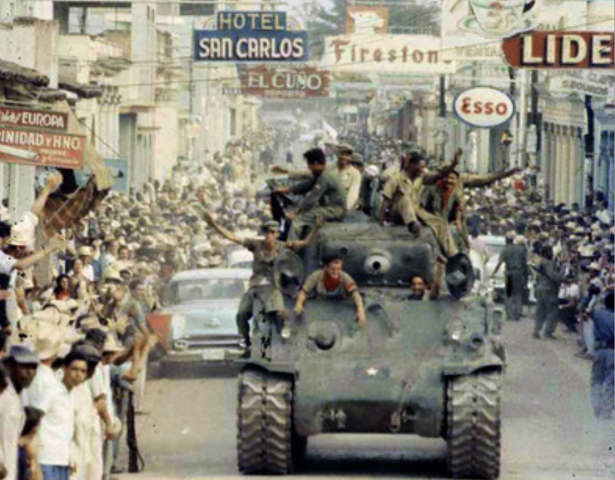

Of course, the charges did not stick. Batista remained in power; he had taken it with the use of force and the support of the United States. Fidel, in turn, understood that the legal means to fight for democracy, social justice and the people’s sovereignty had been exhausted and that it was time to turn to armed struggle. Nonetheless, in the light of recent events, this case, filed almost 70 years ago, offers us some enlightening reasoning.

Last July 11, hundreds of people came out across the country to protest, provoked by a political-communication campaign organized abroad, among other factors. Some were understandably tired of irregular electrical service and power cuts, and exhausted by the pandemic which at that time had reached the most critical period for our country. Others simply joined in to express their animosity toward the government and the socialist model in place. Among the latter, were some who resorted to violence, throwing rocks, bottles, attacking those defending the constitutional order - civilians and authorities alike - overturning cars in the public right of way.

There were also miserableopportunists who took advantage of the social commotion to sack establishments, rob household appliances, loot stores... The evidence corroborating these acts was provided by the perpetrators themselves who, intoxicated by the momentary impunity of their acts, uploaded photos and videos of their "exploits" on social networks.

By the evening of July 11, relative calm had been restored. Many citizens were arrested and charged. Once those who had behaved peacefully - or were inadvertently caught up in the events and unjustly arrested - were identified, they were released within a few days. Some filed legal complaints, turning to mechanisms of our socialist rule of law, and are today walking the streets of their respective cities, as this process advances.

But those who took advantage of the difficult hours to attack others, to destroy; those who used the confusion as an opportunity to steal; those who believed that the Revolution had collapsed and that it was time to aggravate the chaos with insults and rock-throwing, even attacking hospitals, these individuals were sadly mistaken in harboring the illusion that their actions would go unpunished, and today they face the legal consequences of their conduct.

The enemies of the Revolution lost no time in casting those accused of serious crimes as "political prisoners," even before the judicial processes had concluded. Just as in 1952, when there were those who attempted to anoint Batista with the sacred title of a revolutionary, today, the chorus of reactionary hysteria seeks to present thieves and aggressors as "victims of the Cuban regime," in a semantic war intent upon distorting concepts in an attempt to dignify the incorrigibly dishonorable.

We will respond to these pretenders with Fidel’s words in 1952, "... for Jiménez de Asúa, the jurists’ professor, only "those who fight for a social regime of an advanced nature looking to the future" deserve to be considered political criminals, “never reactionaries, never the retrograde, never those who serve the interests of ambitious cliques. They will always be common criminals, for whom taking power by force will never be justified."

Spread the word