There’s no denying that strong labor movements often thrive in urban centers. The organization of capitalist production in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while heavily exploitative of workers, also created the conditions for robust forms of worker organization. Being densely packed in cities that were relatively close to their workplaces allowed industrial workers to form deep bonds of solidarity with each other. Apart from the shop floor, these workers were likely to also interact with each other in other social spaces common to cities.

But how does the labor movement fare in the suburbs? Traditionally, the suburbs are thought of as bastions of conservatism, where workers go to become atomized consumers free from the common public spaces that feed solidaristic action.

Indeed, the business class has long believed this. While commentators often examine the offshoring of manufacturing jobs, not nearly as many focus on the relocation of urban jobs to the suburbs. This process was already well underway in the 1950s and ’60s.

Despite the very real challenges that suburbanization present, the labor movement cannot resign itself to the impossibility of maintaining strong unionism in the suburbs. History can serve as inspiration here.

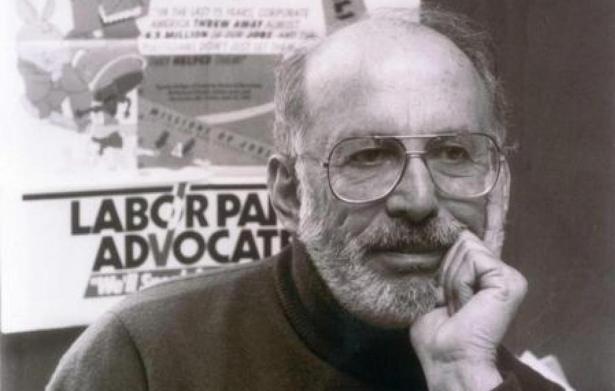

In the early 1950s, the Helena Rubinstein women’s cosmetics plant was moved from Queens to the leafy suburbs of Long Island. Tony Mazzocchi was president of the union representing its workers: Local 149 of United Gas, Coke, and Chemical Workers’ Union (Gas-Coke). While today Mazzocchi — whose life is best chronicled in Les Leopold’s book The Man Who Hated Work and Loved Labor — is known in labor circles for his pioneering work in the realm of workplace health and safety, he cut his teeth building in the heart of the suburbs one of the most well-organized, militant, and effective union locals in the country.

The new Rubinstein plant was located in Long Island’s North Shore, a beautiful setting that seemed to make worker discontent impossible — not just because of its geographic setting, which seemed to discourage aggressive trade unionism, but also the times. Red-baiting within the labor movement was at its peak in the early 1950s, and Gas-Coke had experienced purges of leftists already in the late 1940s. But the overwhelming anti-communism still could not eliminate all residues of good trade union culture.

There were many Local 149 members who had worked in the Queens plant and retained powerful memories of the union’s earlier, bitter struggles. The local’s 1941 strike was a defining moment, as workers successfully resisted the use of scab labor in an attempt to break the strike. These members also came of age at a time when strong working-class culture thrived in their communities. For these people, joining a union was just simply something you were expected to do. Scabbing could mean total social ostracism.

Mazzocchi knew he had to rebuild a union local in the suburbs, but he couldn’t build the local of his dreams overnight. He had to build a base, and started on the level of basic member involvement. Shop stewards and members of other committees were invited to attend Executive Board meetings. As a measure to increase democracy, all new committees were selected by rank-and-file members instead of the Executive Board. His chief contract objective was to eliminate the use of a two-tier wage structure, in which one group of older workers earns significantly more than new hires, which was snuck in to the previous contract under the old leadership.

Like any good union organizer, Mazzocchi knew that a credible strike threat was the best way to make gains in the contract. For over a year before the contract expired, the union prepared for a showdown with the company. Members were asked to give special dues for a strike fund, and the local rented a very visible strike headquarters that the company could see. These moves brought back memories of the open-ended 1941 strike to management.

In an ingenious move, Mazzocchi mobilized the membership to support other unions’ battles to develop their own picket-line chops. They were consistent in supporting workers at surrounding facilities like Reeves Instrument, Arma, Sperry, and Republic.

Mazzocchi reflected, “We were persistent. We were there in countless strikes, and we were bringing out large groups of people. We developed a reputation as a militant group on Long Island. And our women were just as tough as our men.”

As Local 149 increased its battle readiness, it took a psychological toll on the company, which consistently had to start production late in the mornings as workers arrived on buses back from combative picket lines. According to Mazzocchi, “The company was scared shitless. They knew we were having a pitched battle with those Nassau County cops every day. The company figured, if you’re going to do this on somebody else’s picket line, what are you gonna do when it’s your own?”

This aggressive mobilization and preparation yielded results: the two-tier system was eliminated without them even having to strike. Local 149 also became the first in the nation to win full dental coverage.

But Mazzocchi wanted the union to become more than just an effective instrument of collective bargaining. He viewed labor unions as a vehicle for a broader political movement of working people:

The union had to be more than a shop-floor institution. It had to have a broader political understanding. I mean, I understood that corporations dominated the political scene. And that if you were going to fight effectively, people had to understand, ideologically, the need to deal with this huge corporate sector. I knew when I became president of the local, it was a fight for the minds of the people.

Political education was key to realizing this vision. As members became more involved in the union, Mazzocchi sent these lieutenants to all kinds of political meetings to broaden their understanding of labor politics. Ordinary working-class people in Local 149 got to hear from legendary figures like A. Philip Randolph and Transit Workers Union leader Mike Quill, then report back to the larger membership. Others went to Cornell University’s labor school to learn how to produce a quality union newsletter.

But Mazzocchi, a high school dropout, also understood that he had to get people reading. He strongly believed that people needed to have a broader ideological commitment if they were going to stay in the movement for the long haul: “Unless I had a group who, politically and ideologically, understood the meaning of trade unionism — that it was more than just winning a grievance in the shop — we’d lose people.”

He started a weekly book group that became legendary within the local. Incredibly, its participants did not include a single high school graduate. Once people were hooked, there were no limits to the topics they covered. Even The Iliad got put on the reading list.

Workers were transformed when they read Freedom Road, a powerful account of the promise and failure of Reconstruction. Members came away with a more concrete understanding of how race is used to divide working people to the benefit of the boss. The reading group inspired a campaign to demand the company hire more black workers — a campaign that some workers threatened to refuse to work with them on. Mazzocchi held firm, and these workers eventually accepted it. The local also raised money for a station wagon to help transport black people in Montgomery during the Montgomery bus boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr.

Even as Local 149 became more ideologically driven, its leadership never lost sight of winning concrete material gains for the members. This is how Mazzocchi maintained the loyalty and support of the members as he brought them into uncharted territory (and skillfully avoided red-baiting along the way).

Bobby Guinta, one of his closest lieutenants, explained, “Tony never spoke in radical terms, never used any of the radical terminology. It was just the normal practicing of real good trade unionism which altered people.”

Local 149 injected something else into their members’ lives: fun. Most of the jobs at the Rubinstein plant involved little more than lifting and moving boxes. But the union made work more than that. It became a place of exchanging exciting ideas and developing deep social bonds.

In 1953, the local started a bowling league as a way to have social outlets independent of company control. The bowling outings became notorious as a site of flirtatious, raucous fun between members. They became so popular that even managers started preferring them to the company’s social outings.

The local used the talents of its members to start a newsletter titled The Militant. It covered important political topics beyond the shop floor like automation, the merger of the AFL and CIO, and the McClellan Senate hearings. To keep things in balance, juicy workplace gossip was also included as well.

Local 149 literally changed peoples’ lives. Mazzocchi later recalled, “Life became exciting. The job was more than just the job. Everybody waited till the day was over, so we could go out and do something else, and then come right back in. It was a fight. You know, people were proselytizing all the time.”

The local was featured in Barbara Garson’s study All the Livelong Day: The Meaning and Demeaning of Routine Work. Her conclusions confirmed the lived experience of workers on the shop floor, stating that the local was “one of the best union locals in the country. It’s militant, it’s democratic, it has the highest pay in the industry, and it has never given up the daily struggle on the shop floor.”

For Garson, the union had achieved the incredible task of humanizing repetitive manual labor:

The right to respond like a person, even while your hands are operating like a machine, is something that has been fought for in this factory. And this right is defended daily, formally through the grievance process, and informally through militantly kidding around.

The story of Local 149 should be an inspiration to those of us who are trying to rebuild the labor movement today. The terrain of class conflict is certainly different in 2022. But the 1950s suburban environment that Mazzocchi faced, which included intense red-baiting as well as the suburbanization of work, was no more hospitable.

Unions must become a powerful social force in workers’ lives beyond grievance procedures and contract administration. Yes, working people need material improvements in their lives in the form of wages and benefits. But we also need to be won over to and inspired by a broader political movement — this is where long-term commitment and enthusiasm comes from. Tony Mazzocchi and Local 149 did just that, in a suburban environment where no one thought it possible. We can today, too.

Paul Prescod is a high school social studies teacher and member of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

Have you read Jacobin in print? Subscribe at a special rate and don’t miss our latest edition.

Spread the word