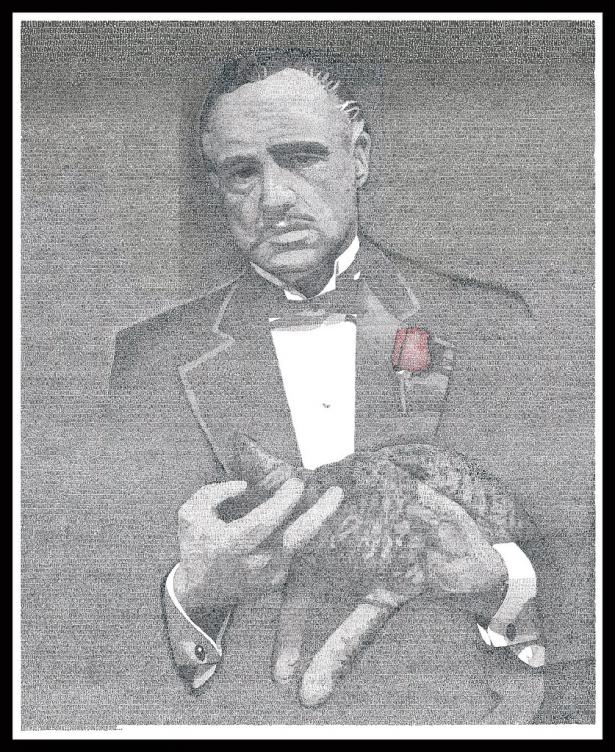

They do love The Godfather, all those men—and it’s almost universally men—who quote the film’s well-worn lines, as if Francis Ford Coppola and Mario Puzo’s masterpiece of movie making, is also a darkly comic guide to creating and wielding power in America.

I once interviewed a “former” mobster—if such a person exists—who described seeing The Godfather with a group of fellow criminals who were so pleased and excited afterward that they felt compelled to go out and hijack a truck to celebrate. Well, of course they loved The Godfather: It reinforces every sentimental cliché held dear by the members of a cult devoted to criminal enterprises performed by sociopaths who destroy lives and spread corruption… you know, fun stuff.

As the torrents of reverential prose praising the film upon its fiftieth anniversary flood newspapers across America, it’s instructive to look at the individuals who inspired the film, their self-serving myth-making, and the ways The Godfather perpetuates those myths.

In his preface to the 1996 re-issue of his novel, Puzo wrote, “Whenever the Godfather opened his mouth, in my own mind I heard the voice of my mother. I heard her wisdom, her ruthlessness, and her unconquerable love for her family and for life itself….”

That explains a lot. And you have to give it to Puzo. He cunningly used this memory to reimagine a monstrous exploiter of weaker men as a benevolent father.

It’s widely thought that Don Corleone is a composite of the heads of several mob families. There’s Frank Costello, who was known as the “Prime Minister of the Underworld,” owing to his political connections, professed abhorrence of violence, and his very public denial of involvement in the narcotics trade. Like Don Corleone, Costello had a quiet, raspy voice—the result of a botched childhood throat operation, though Costello’s accent was far more resonant of the streets of New York than Brando’s idiosyncratic creation.

Don Corleone is said to have “all the judges and politicians” in his pocket, and that was certainly true of Costello who was the de facto boss of New York’s Tammany Hall in the middle of the twentieth century.

Another model for the Don is Joseph Profaci—known as the “Olive Oil King”—who was head of one of the original five New York Mafia families. Like the Brando character, Profaci used an olive oil importing company as a cover for his less wholesome pursuits. Today, the Profaci family is still in the olive oil business. Unlike Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone, the Profacis have succeeded in going legit. It’s not exactly the “Senator Corleone or Governor Corleone” that Don Corleone wishes for his son, though one could argue that these days making good olive oil is a worthier calling than serving in the U.S. Senate.

But looming above these influences is the pretentious voice of another pioneering mob boss, Joseph Bonanno. His bestselling 1983 memoir, A Man of Honor, is based on the notion that old-school Mafia guys adhere to a lofty Sicilian tradition and moral code that was tossed aside by subsequent generations.

In Bonanno’s self-justifying autobiography, he refers to the heads of mob families as “Fathers” who uphold the tenets of their “honorable society.” Bonanno also displays a rare gift for self-praise, as in this inadvertently comic passage:

It is difficult to talk of oneself without prejudice. In general, people considered me an attractive man. They generally praised my charm and intelligence. I liked to dress well, but I preferred to evince an air of subdued good taste rather than gaudiness. My one touch of flamboyance was my pinky rings. I had rings displaying ruby, sapphire, jade, and onyx.

Now that is funny. But what is less amusing is the way that this “man of honor” denies any involvement in narcotics trafficking, a claim that is convincingly debunked by mob historian C. Alexander Hortis in his deeply researched book The Mob and the City.

In his memoir, Bonanno tells us, “My tradition outlaws narcotics. It has always been that ‘men of honor’ don’t deal in narcotics.” Alas, it ain’t so, according to Hortis, who writes, “Mafiosi were involved in illegal narcotics almost from the beginning. Nor was the trafficking confined to younger, low-level underlings.”

So, given the sordid history of the men who served as models for The Godfather, it’s appropriate to ask: What—and who—do we love when we love The Godfather?

Of course, the film is easy to love with its haunting musical theme, one of the greatest ensemble casts in movie history, and its splendidly seductive laconic pace.

“The problem with this vision of good and bad mobsters, of course, is that all the real mobsters were very bad.”

Take the masterfully directed opening scene in which Don Corleone bestows favors on the day of his daughter’s wedding as if the mob were the Italian version of Hadassah. Here we have the Mafia as a powerful family that protects its members and faithful friends from a hostile world as it dispenses its own form of justice.

This is certainly an alluring fantasy familiar to anyone who was bullied in childhood: The Mob vows to take down that thick-necked creep who stole your lunch money. No wonder so many grown-up men who were once frightened little boys love this movie and laugh with admiring glee when Brando promises to make the famous offer that can’t be refused. Yeah, that’s strangely funny, but not comfortably so, at least not to me.

Elsewhere The Godfather depicts mob life as consisting largely of the Corleone family playing a lethal game of tag with their rival mobsters.

The “bad” mobsters who want to sell narcotics try to kill the “good” mob boss (Brando). Then his son (Pacino) kills a bad mobster and a bad cop. Pacino’s Michael Corleone is now “it,” so he must hide for a while in Sicily.

As this back-and-forth plays out, those who are shot or beaten by the Corleone family and their loyalists always deserve what they get. James Caan’s Sonny Corleone viciously batters his wife-beating brother-in-law with a garbage can; Richard Castellano’s Clemenza famously leaves behind the gun and takes the cannoli as he oversees the murder of a disloyal security guard; and Abe Vagoda’s Tessio acquiesces to his own murder with professional decorum because he knows he’s betrayed the family and it’s only right that he dies. The message is that good mobsters only kill for good reasons.

The problem with this vision of good and bad mobsters, of course, is that all the real mobsters were very bad.

And playing tag with other gangsters is not how old-school mobsters spent their abundant free time. Instead, they killed innocent people like union organizer Peter Panto, who stood up to the mob’s control of the Brooklyn docks. Panto disappeared in 1938, and his body was found 18 months later buried in lime near Lyndhurst, New Jersey. But The Godfather doesn’t tell that kind of story.

Finally, what’s most galling about the film is that it never addresses the question: Where does all the money come from?

Brando’s Don Corleone admits that he traffics in gambling and other activities which his politician friends consider to be harmless vices. Not mentioned is the fact that all mob businesses were made possible by the threat of violence or actual violence. Besides, no real mob family limited themselves to harmless vices. Their money came from loansharking, racketeering, prostitution, hijacking, and the like, pursuits that are not depicted in the film. So we never see, for example, members of the loving and loyal Corleone family threatening the owner of a small business or breaking the legs of a degenerate gambler who’s behind on paying the vig.

None of which is to say that The Godfather isn’t a masterpiece or that Coppola isn’t a genius director. And yes, I know it’s just a movie, an entertaining fantasy about what some believe to be a quintessential American family. And yes, Coppola wasn’t making a documentary, nor did he claim verisimilitude.

But the film is often called a work of art. So if—as I believe—the best art emerges from a desire to tell the truth, it’s fair to ask why The Godfather fails to tell the whole truth about the world it inevitably celebrates, and why viewers—myself included—are seduced by the fantasy that masks the reality.

Spread the word