Strand was a radical, a founder of the Photo League in New York City in the 1930s, and a teacher who guided its work. After World War Two, as McCarthyite hysteria gripped the country, and especially the world of media and the arts, he was put on a blacklist (along with the Photo League itself) by the U.S. Justice Department. He went into exile in France, never returning to live in the U.S. For the next three decades he photographed people in traditional communities, and in newly independent countries during the period of decolonization and national liberation.

Strand was one of the founders of modernism in photography – the idea that photographs had to be connected with the world and depict it cleanly and simply. He combined those visual ideas with social justice politics, not in a dogmatic or simplistic way, but in an effort to create socially meaningful art with its own philosophy and set of principles.

Strand’s books were documents about place, presenting people in the context of their physical world. The subject of this set of photographs is also a place, one very familiar to me over many years – Portsmouth Square in San Francisco. These photographs were taken over 20 years. I’ve sequenced them, as Strand might have done, I think, in an order that emphasizes their social, as well as visual, content.

I was an organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We set up a Garment Workers Center on Commercial Street, a block from the square. The workers who came into the center were Chinese women and men who worked in shops all over the city, from outer Third Street to Chinatown itself. I was just beginning to take photographs in a conscious way in those days, and because I was a union organizer, there was never a possibility that the sweatshop owners would let me inside to document the conditions. I was a union militant, interested and committed to documenting work, so this was a big regret. But walking through Portsmouth Square every day gave me a sense of the lives of people in this community, in the hours they spent outside the sewing shops.

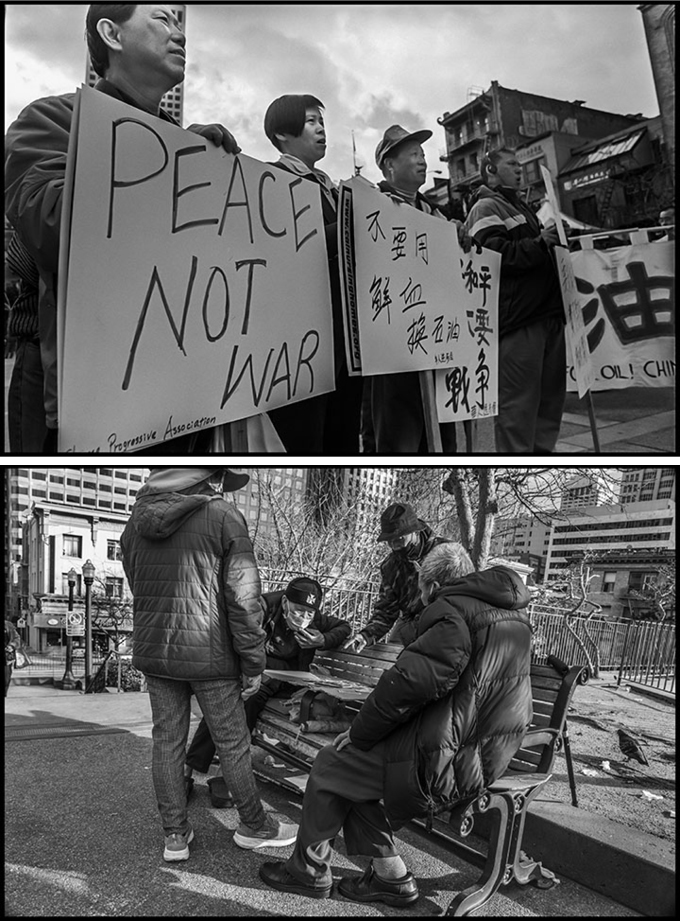

In those years the number of unhoused people on the streets was much smaller than today. I would see perhaps one or two people sleeping on the sidewalk in the twenty blocks I traveled between our union’s central office and the square, and rarely anyone sleeping the square itself. Today that has changed. Like any San Francisco park, Portsmouth Square has been made a home, or at least a sleeping place, by several people with nowhere else to go. The first series of photographs shows a few of these individuals, in their relationship to the facilities of the square, including its benches, castoff cardboard boxes, and the sidewalk itself.

As an organizer I came to realize that Portsmouth Square is home to many activities, and has many levels of meaning to the people of Chinatown. They relax, play cards and enjoy themselves on the benches whenever the city’s notoriously uncertain weather permits. Over the years I’ve often returned to take photographs and been struck by how many people play games here. On one level, it is a place where people get together, in a community where many live with many family members sharing small apartments. Portsmouth Square means space to breathe, to be noisy and extroverted, to play the games people were taught by mothers and fathers in the generations that came before. It is a deep expression of the history and culture people share.

Organized cultural events also take place in the Square. On a recent walk I was pulled towards the performance space by the music of the erhu and other traditional Chinese instruments. An ensemble of musicians, organized by A Better Chinatown Tomorrow, had assembled to give a concert for the card players and the families wandering through the square. One woman sang while another danced – stylized voice and motions in humble street clothes.

The culture of Chinatown includes the social movements in which people organized support for revolutions in China itself, and protests over the oppressive conditions and discrimination that people have faced at work. It is an old history. A few blocks away, in St. Mary’s Square, a statue of Sun Yat Sen by Beniamino Bufano honors the fact that part of the Revolution of 1911, which overthrew the dowager Manchu empress, was planned by Chinese exiles, including those in San Francisco.

Chinatown is one of the politically most vibrant communities in San Francisco, and Portsmouth Square has always provided space for demonstrations, marches, meetings and leafleting. When the bombing began in Afghanistan, and the media began its deafening war drumbeat that preceded the invasion of Iraq, Chinatown’s internationalists gathered in Portsmouth Square. There they held signs calling for peace, and for spending on human needs instead of bombs. After listening to speeches in Chinese, the contingent marched down to Market Street and joined thousands of others from homes across the city, protesting what became a 20-year war.

Perhaps Strand, who took his photographs slowly and deliberately with a large view camera, might have had conflicting feelings in seeing these photographs. In taking them I took advantage of the mobility of a small camera, moving much more freely than he could with his large apparatus. He carefully constructed his images, seeing them on the large ground glass at the rear of the camera. I try to be conscious of the image and its elements as I take my pictures too. But sometimes I feel that not everything happens on a conscious level. Working quickly, I depend on a less conscious part of the brain to order the visual pieces of the image. Perhaps that was also true for him.

“Certain realities of the world had to be made clear. To be deeply moved was not enough.” Mike Weaver on Paul Strand’s philosophy

But what I take from Strand, and what he might have seen as a commonality in our work, are his aesthetic and political principles. In his idea of dynamic realism a successful photograph has to encompass three ideas. It has to be partisan – committed to social change and seeing that change as necessary and possible. Especially after he left the U.S. during the worst of the Cold War years, he worked in collaboration with radical, often Communist, activists. They brought him to the communities he photographed, and wrote text accompanying the photographs.

Strand was a committed realist, but he believed that a successful photograph had to do more than just record the reality in front of the lens. Mike Weaver says in his description of Strand’s philosophy, “Certain realities of the world had to be made clear. To be deeply moved was not enough.” Strand’s concept of specificity meant that an image of a particular person had to go beyond her or his individuality, to encompass a more universal truth. Commenting on a Dorothea Lange photograph he said, “The cotton picker is an unforgettable photograph in which is epitomized not only this one man bending down under the oppressive sky, but the lot of thousands of his fellows.”

Strand did not deny the individuality of the people in his images. None could have had more dignity, or been photographed with greater care or in more detail. But without being able to see beyond the individual to greater universality, “photography collapsed into record making, emphasizing the exceptional at the expense of the universal … One person who has been studied very deeply and penetratingly can become all persons. Therefore it seems to me that art is very specific and not at all general.”

Strand’s third principle was dimensionality, referring both to the qualities of the image itself, and how they resonate with its social content. In an image different elements have a relationship to each other, just as the photograph has a relation to the reality it depicts. That relationship, within the image, has to have a sensation of movement, he believed. Even a very still, posed photograph has to have “a sensation of movement through the eye … simply a reflection of the material fact that everything is in movement … It is the reflection that in the world things are actually related to each other, even though sometimes we cannot readily see it.”

These images of Portsmouth Square have been assembled into a sequence, as Strand did in his careful juxtaposition of the images in his books Some were taken twenty years ago and the most recent just a few weeks back. Over this period of time I was able to work, and see Portsmouth Square, as an activist myself – an organizer and participant, or sometimes a supporter at a distance, of some of the community’s social movements. The images document the reality of people enduring the pain of marginalization, of the social networks and culture centered on this place, and the efforts to change social reality and fight for justice.

Whether the images succeed in attaining Strand’s goal of specificity, or universality, and how well they work as images internally, is up to the viewer to judge. But taking and sequencing them has forced me to reexamine my own process as a photographer. I’ve always considered myself a realist and materialist. I’ve paid a lot of attention to the relationships that make my work possible, and I hope socially useful. But I’ve given less thought to the aesthetics or the principles behind their conception. It’s seemed enough to say that a photograph either works or it doesn’t.

Strand, however, demands a greater commitment. He voiced a political philosophy that provides a coherent way to analyze photography that is deeply connected to the world. That forced me to give more attention to the way politics and aesthetic ideas interact in my own work. Here’s his reaction to the unconsidered and unthought realism (photojournalistic and otherwise) of his day (he died in 1976):

“We must reject both this venal realism as well as the mere slice-of-life naturalism which is completely static in its unwillingness to be involved in the struggle … towards a better and fuller life.

“On the contrary, we should conceive of realism as dynamic, as truth which sees and understands a changing world and in its turn is capable of changing it, in the interests of peace, human progress, and the eradication of human misery and cruelty, and towards the unity of all people. We must take sides.”

Thanks to “Dynamic Realist,” by Mike Weaver, in “Paul Strand, Essays on his Life and Work”, Aperture, 1990

All photographs by David Bacon

[David Bacon is a Bay Area writer and photographer, and former union organizer. His latest book is In the Fields of the North / En los campos del norte (Colegio de la Frontera Norte/University of California Press, 2018). View all posts by David Bacon →]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word