Since Vladimir Putin invaded Ukraine on February 24, most western media accounts have assumed that his goal is to conquer the entire country, overthrow the elected government, and replace it with a pro-Russian regime. These reports, and the maps that accompany them, often fail to take into account the different regions of Ukraine, and how Russia may covet some more than others.

This is the same fundamental error that accompanied early reports on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which often overlooked internal ethnic and religious territoriality in those countries, and used top-down political and military analysis that treated them only as unitary states. It wasn’t until later in those wars that maps of ethnic and sectarian divisions began to explain the patterns of resistance to U.S. occupation. Like those two countries, Ukraine is not just a piece on a geopolitical chess board, but a place, with its own rich diversity and relationships among peoples.

Moreover, western media tends to treat the Ukraine conflict only in the light of the 20th-century Cold War, assuming that the former KGB agent Putin wants to recreate the Soviet Union. Yet Putin has said the exact opposite, in a flourish of anti-Communist rhetoric that preceded the invasion. His vision is clearly of a renewed Russian Empire, but analysts from recent settler-colonial states have difficulty understanding that memories can extend many centuries earlier than the mere 74-year life of the Soviet Union.

From my background and teaching college classes about the geographies of Russia and East-Central Europe, it is becoming clear to me that Putin’s ultimate goal is to carve off a distinct Russian-speaking region from Ukraine. Because he would rather bite off a large chunk of Ukraine rather than swallow it whole, the partition of Ukraine is very much on the table.

The maps in Putin’s mind

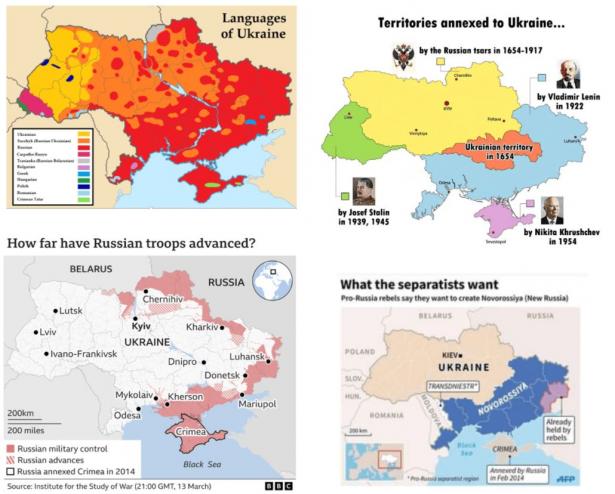

Maps matter. In the case of Ukraine, the first map that shows the predominance of Russian-speakers across eastern and southern Ukraine (reprresented in red) matters very much to Vladimir Putin. In his unhinged February 21 address to the nation, he reminded Russians that “in the 18th century, the lands of the Black Sea littoral, incorporated in Russia as a result of wars with the Ottoman Empire, were given the name of Novorossiya” (or New Russia).

It was not the first time that Putin referred to the swath of Russian-speakers in southern and southeastern Ukraine as “Novorossiya,” and treated that region as distinct from the western Ukrainian-speaking region (in yellow) and the mixed Ukrainian-Russian region (in orange). Russians also refer to central Ukraine as “Malorossiya” (Little Russia), and the northeastern borderland around Kharkiv and Sumy as “Sloboda Ukraine.”

In the same speech, Putin excoriated Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin for giving away a portion of Russia to the new Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1922, the lands that today form eastern and southern Ukraine (as shown in the second map). Putin claimed that “modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia. This process started practically right after the 1917 revolution, and Lenin and his associates did it in a way that was extremely harsh on Russia — by separating, severing what is historically Russian land. Nobody asked the millions of people living there what they thought.”

Putin continued with his denunciation of Lenin, whose “ideas of what amounted in essence to a confederative state arrangement and a slogan about the right of nations to self-determination, up to secession, were laid in the foundation of Soviet statehood…. What was the point of transferring to the newly, often arbitrarily formed administrative units — the union republics — vast territories that had nothing to do with them? ….When it comes to the historical destiny of Russia and its peoples, Lenin’s principles of state development… were worse than a mistake, as the saying goes. This became patently clear after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991…. Soviet Ukraine is the result of the Bolsheviks’ policy and can be rightfully called ‘Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine’.”

So in his speech laying out his irrational rationale for invading Ukraine three days later, Putin did not necessarily question the existence of a Ukrainian Soviet republic, but focused primarily on how Lenin detached Russian-speaking regions (including the Donbass) to join with that republic. Lenin had attached those lands to Ukraine, in order to weaken the “Great Russian Chauvinism” that he identified as the ideological underpinning of the Czarist Russian Empire, and to some extent to make the new Ukraine more multiethnic and less interested in independence.

When the Soviet Union inherited the Russian Empire’s domains after the 1917 Revolution, Lenin’s vision was as of a country in which ethnic republics were in free association with each other, and he granted independence to Poland, Finland, and the Baltic states (though not Ukraine). As Putin approvingly pointed out, Josef Stalin quickly reversed that self-determination policy after Lenin’s 1924 death, by making the ethnic republics autonomous in name alone, as regions ruled solely from Moscow.

As Putin angrily recalled, Nikita Khrushchev in 1954 gifted majority ethnic Russian Crimea to Ukraine (also shown in the second map). And to Putin’s great disapproval, Mikhail Gorbachev restored Lenin’s vision in the late 1980s, by granting the ethnic republics greater autonomy, an act which Putin blamed for the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union. Putin viewed 1991 in a wider historical lens as the collapse of the Russian Empire, stranding 25 million Russians (or 17 percent of all Russians) outside Russian Federation borders. In Ukraine, annexing Crimea in 2014 and recognizing the eastern Donbass republics in 2022 were his first steps toward taking back the lands that Russia “lost” in 1922.

The risks of swallowing Ukraine whole

As Putin launched his invasion, his forces pushed into eastern Ukraine from Russia and the eastern Donbass, into southern Russia from Crimea, and toward Kyiv from Belarus. His missile and air attacks have hit military and civilian sites all over the country. So if we view Ukraine solely as a unitary state, it looks like Putin is heading for “regime change,” in order to topple Volodymyr Zelensky’s government, and occupy and rule the entire country.

But according to Finland’s President Sauli Niinistö, Putin personally denied to him that “regime change” was his goal in Ukraine. Given Putin’s long track record of lies, we can certainly take any of his claims with a few tons of salt. But the facts on the ground are consistent with a takeover of only part of Ukraine, not the entire country.

If you superimpose Russian ground advances (in the third map) over the red Russian-speaking area in the first map, you can see that nearly the entirety of the advances are in the Russian-speaking regions, which tended to vote for pro-Russian politicians in most elections before Zelensky’s 2019 victory. Other than air attacks, there have been no ground advances or paratrooper landings into the Ukrainian-speaking western region or most of the mixed Ukrainian-Russian central region.

The only major exception is the mixed capital of Kyiv itself, which Russian forces are attempting to encircle or capture. Attacking and besieging Kyiv keeps Ukrainian forces pinned down in the north, and capturing it would force Zelensky to capitulate and meet Russian terms. But that does not necessarily mean that Kyiv would be occupied in the long term. Even after the refugee exodus of the past few weeks, at least two million Ukrainians remain in Kyiv. If the capital falls, many of them would continue to resist Russian occupiers as vengeful and well-organized urban insurgents.

The invasion has been enough of a slog for Russia, and even Putin has to understand that a Ukrainian insurgency would be turn the country into a quagmire, recalling Moscow’s 1989 defeat by mujahedin rebels in Afghanistan. As the American experience showed in Baghdad and Kabul, or the Israeli experience in Beirut, holding a major metropolitan area in the face of insurgent resistance is a formidable challenge. It may be relatively easy to seize a capital, but that does not make the whole country fall into an occupier’s hand.

If Russia was truly set on taking control of all of Ukraine, it would also have to deal with strong Ukrainian resistance in the far western region of Galicia, around Lviv. Galicia was part of interwar Poland, and during World War II was the stronghold of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA), which fought the Soviets and welcomed the Nazi invaders, until they found the German Reich wanted farmland for settlers more than they wanted allies as puppets. The UPA resistance, in contact with the CIA, continued fighting the Soviets for seven years after the war’s end, until 1952.

The far west is still the center of Ukrainian ultranationalist groups, who have welcomed fighters from the West for training. The proximity of the Polish border would enable the clandestine delivery of NATO weapons, much as the Afghan mujahedin were sustained with U.S. weapons supply lines from Pakistan. (And also like the mujahedin, the West may later regret blowback from arming far-right militants who do not share democratic values.)

Resistance in the mixed middle

Resistance to a Russian occupation would also come from the mixed region of central Ukraine (in orange on the first map), where not only are Ukrainian-speakers and Russian-speakers mixed together, but many speak a hybrid tongue known as Surzhyk. Like in Bosnia or Iraq, it is impossible to turn such a messy ethnic map of mixed communities, families, and individuals into “clean” political borders without massive violence.

“Ukraine” actually means “borderland,” and it is instructive to read Gloria Anzaldúa’s classic Borderlands / La Frontera to understand the similar rich hybridization of languages in the U.S. Southwest (formerly northern Mexico). She might as well have been describing the complex borderland of Ukraine. My own family roots in Hungary have made me aware of how history is full of both conflict and cooperation among peoples.

Ukraine’s language map gets even more complex because many self-defined ethnic Ukrainians actually speak Russian as their first language, just as many Mexican Americans speak English at home. In the same way, a majority of Irish, Scots, and Welsh speak the language of the English colonizer at home, rather than their own Celtic tongues, but many of them are still strong nationalists. Self-identified ethnic Russians form only about 17-22% of Ukraine’s population, and form a majority only in Crimea and the secessionist eastern Donbass.

In the rest of Ukraine, however, Russian-speakers (both ethnic Ukrainians and Russians) have not at all welcomed Putin’s invasion. Like the Americans in Iraq, Putin may have thought his troops would be welcomed with flowers and red-white-and-blue flags, but instead they’ve been greeted with grenades and anti-tank weapons. In the 2019 election, Zelensky received a higher percentage of votes from Russian-speakers than from Ukrainian-speakers, in a rebuke to ultranationalists on both sides.

Even Russian state TV cannot manufacture a scene of ethnic Russians cheering on Putin’s troops, which was so easy to find in Crimea eight years ago. In fact, most of the civilians killed in the war so far have been Russian speakers. And in Russia itself, because soldiers and civilians were not sufficiently hyped up in advance for war, Putin may be losing their hearts and minds as well.

Partition is in the cards

With the conquest of all Ukraine off the table, Putin may still fantasize about biting off “Novorossiya” from the rest of Ukraine. He had suggested partitioning Ukraine as far back as 2014, when he casually suggested to Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk that Poland should take back Galicia. NATO’s former supreme allied commander for Europe, retired Adm. James G. Stavridis, confirms that “the most probable endgame, sadly, is a partition of Ukraine. Putin would take the southeast of the country, and the ethnic Russians would gravitate there. The rest of the nation, overwhelmingly Ukrainian, would continue as a sovereign state.”

Russian military advances (in the third map) are clearly attempting to create a corridor from the eastern Donbass to Crimea, including the devastating bombardment of the port city of Mariupol on the Sea of Azov, the key point of connection between Donbass and Crimea.

Going west along the Black Sea coast, Russia has occupied the Dnieper River city of Kherson, and is said to be attempting to set up a “Kherson People’s Republic,” similar to the Donetsk and Lugansk “people’s republics” it has recognized in the eastern Donbass. The city’s residents are bravely protesting the occupation and the secessionist plot. The Russian plans for Kherson’s “independence” begs the question: if Putin’s goal is really to soon conquer and govern all of Ukraine, why would that game plan include breaking away more pieces from Ukraine? The Kherson gambit may be further proof that partition is his real end game.

As the Russian offensive advances farther west, it is now encircling Mykolaiv. If that major city falls, the next to be targeted will be Odesa, the headquarters of the Ukrainian navy. The conquest of that key port city would complete the corridor westward to Transnistria, an ethnic Russian enclave that declared independence from Romanian-speaking Moldova in 1992, and has hosted Russian “peacekeepers” ever since. At that point, Putin’s dreamt-of “Novorossiya” connecting Russian-speaking eastern and southern Ukraine (as shown on the fourth map) would be realized.

The entity could be a loose collection of “people’s republics” along the Black Sea coast (which not coincidentally is rich in offshore natural gas deposits), the far-east Donbass, and perhaps even “Svoboda Ukraine” along the northeastern border. The swath could also be coalesced into a single Russian-occupied state that declares so-called “independence” and is recognized by Moscow. Or the entire region could be annexed outright to Russia as Crimea was in 2014, perhaps after a “referendum.”

Or Putin might have an even more diabolical plan in mind, one that has a precedent, which includes securing NATO approval for partition. That precedent is in the 1992-95 war in Bosnia, which pit Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) against both Serbs and Croats. Just as the break-up of the Soviet Union left many Russians outside Russia, the subsequent break-up of Yugoslavia left many Serbs outside Serbia, including in Croatia and Bosnia. The U.S. opposed ethnic cleansing by the Russian-aligned Orthodox Serbs, but facilitated ethnic cleansing by its Catholic Croat allies.

The 1995 Dayton Accords brought an end to the Bosnian war, by partitioning the country into a Serb-ruled Republika Srpska, and a Muslim-Croat Federation. “Dayton” referred to the Ohio city near the Wright-Patterson Air Base where the talks were held, hosted by President Bill Clinton. In effect, Clinton and NATO rubberstamped the wartime ethnic cleansing on both sides, by recognizing the “clean” political border between the two new ethnic republics.

While Bosnia-Herzegovina is nominally still an independent state, the real power is exercised by the two de facto ethnic statlets within it. The shaky arrangement threatens to collapse every time an irredentist Serb leader threatens to secede and join Serbia. As the partition of British India and Palestine have long demonstrated, partitions rarely bring peace, and more often set the stage for decades of war. But Putin may be tempted to put a Dayton-style partition of Ukraine on the table, since the U.S. and NATO has already backed that settlement model in Bosnia. The U.S. similarly oversaw a similar de facto internal partition of occupied Iraq into Kurdish, Arab Sunni, and Arab Shi’a regions.

Ukraine without “Novorossiya”

If “Novorossiya” emerges from the maelstrom as a nominally Russian-ruled region, what would happen to the rest of Ukraine, the mostly ethnic Ukrainian western and central regions? In some ways, Putin’s war has activated a self-fulfilling prophecy, creating the very far-right, pro-NATO Ukrainian bogeyman that he pretends to abhor.

Whether or not Zelensky remains in office, this “rump Ukraine” would probably be much further to the right, hardened by war, and elevating the resistance of ultranationalist militants, such as the Azov Battalion. (A counterview could be that the far-right militias no longer have a monopoly on militancy, so they’ve been eclipsed by other Ukrainian “heroes.”) The reduced-size Ukraine would almost certainly support joining NATO, though a peace deal would probably include Ukraine’s neutrality.

Why would Putin tolerate creating a rump Ukraine that is even more dead-set against Russia? A geostrategic answer is that his Novorossiya would form at least a small “buffer” between NATO and Russia. My more cynical answer is that is a sustained Ukrainian enemy is exactly what Putin wants and needs. In the same way that Ukrainian and Russian ultranationalists have reinforced each other’s messages of hate, Putin’s aggressions and NATO’s expansions have fed off of each other’s messages of military might. They actually need each other, to generate fear among their own people.

Like many western leaders, Putin’s main goal is to stay in power, especially in the face of economic crises at home, and a good way to always is stoke fear and xenophobia abroad. An independent Ukraine simmering with anger would enable Putin to continue to scare his own people with “NATO and Nazis,” and exploit Russia’s historical traumas associated with threats from the west. Without an enemy abroad, he may not be able to maintain control at home. So although partition would hardly placate Ukrainians, it might be the outcome he needs to keep ruling over Russians.

[Zoltán Grossman is a Member of the Faculty in Geography and Native American and Indigenous Studies at The Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. He earned his Ph.D. in Geography from the University of Wisconsin in 2002. He is a longtime community organizer, and was a co-founder of the Midwest Treaty Network alliance for tribal sovereignty. He was author of Unlikely Alliances: Native and White Communities Join to Defend Rural Lands (University of Washington Press, 2017), and co-editor of Asserting Native Resilience: Pacific Rim Indigenous Nations Face the Climate Crisis (Oregon State University Press, 2012). His faculty website is at https://sites.evergreen.edu/zoltan]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word