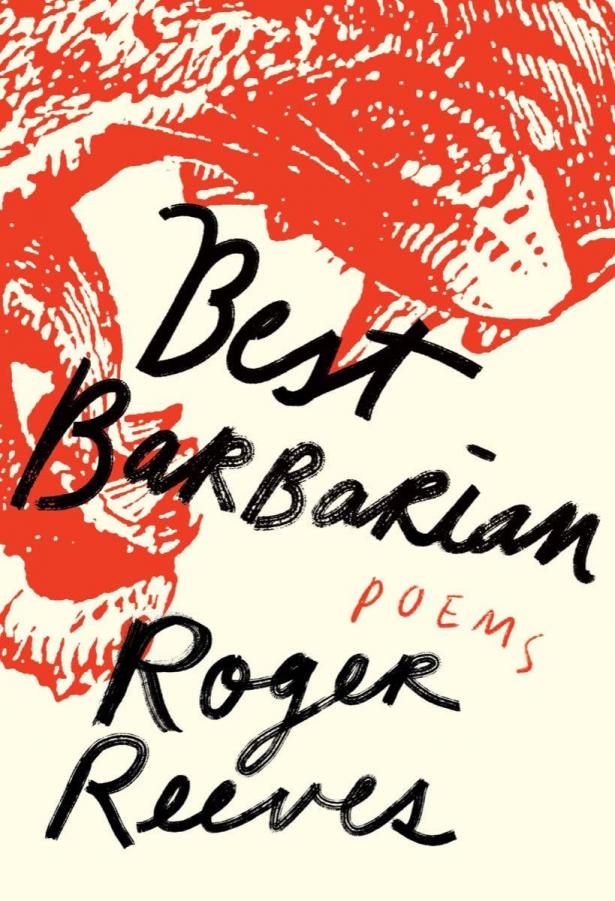

Best Barbarian

Poems

Roger Reeves

W.W. Norton & Company

ISBN: 978-0-393-60933-2

Proceeding in prayerlike incantation, “Best Barbarian,” Roger Reeves’s terrific second collection, eruditely sets out to unite the Western literary canon with its omissions and oppressions. These poems resurrect an eclectic cast of characters, from Sappho to James Baldwin, to reflect on the poet’s vital yet unanswerable question: “What disaster will I deliver to my daughter?” From playful abecedarians to a psychedelic “durational” poem (which, when read aloud, is roughly the length of the Alice Coltrane song that inspired it) the reader traverses a sonic landscape from elegy to ecstasy.

“Domestic Violence,” a stunning poem situated midway through the book, is narrated by Louis Till, a Dantesque figure running frantically through a hallucinatory, lyric underworld in search of poetic lineage and his place in the afterlife. As in the “Divine Comedy,” key literary figures emerge in the poem’s fiery passageways. A ghoulish Ezra Pound appears, demanding to serve as the narrator’s Virgil — but Louis, suspicious of his motives, runs away. “Ezra,” he proclaims, “be here in your cage and free.”

It is widely known that Pound was a staunch supporter of Mussolini. In 1945, he was arrested for treason in Pisa by American forces and imprisoned in a steel cage. From that legendary confinement, he composed the “Pisan Cantos,” a section of one of the most canonical works of 20th-century poetry. What is less known, however, is that Louis Till — Emmett Till’s father — was detained on murder charges in the same facility as Pound. This uncanny historical juxtaposition, coupled with the mention of Till’s execution in the “Pisan Cantos,” could have easily remained a scholarly footnote. But in Reeves’s deft hands (“And when all the voices/sound like the police, I said, kill all the voices”) the peripheral is made central as a way to upend literature’s hierarchies.

Louis runs toward more fitting guides: three Black artists, Audre Lorde, Gwendolyn Brooks and Lucille Clifton. These prophetic women generate a metaphoric looking glass that permits Louis to see himself in Sandra Bland, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner and other Black victims of police violence. This, in turn, calls his guilty verdict into question and prefigures the violent murder of his son. “Guides,” Louis asks, “where have I entered?” Reeves responds with an eerie image of the names of the dead rolling on a field. If this is the Inferno, what is Paradise? The poet tells us: Paradise is “the end of running.”

“Evil has no father,” Toni Morrison asserts in “Grendel and His Mother,” her feminist essay on “Beowulf.” She continues: “In true folkloric, epic fashion, the bearer of evil, of destruction is female.” In Reeves’s iteration, this misogynist archetype is completely subverted. For him, Grendel’s mother is a Black mother, despairing over her murdered son:

When my son called to me, called me out of heaven

To come to the crag and corner store

Where it was that he was dying, Mama,

I can’t breathe; even now I hear it — the limb

Of him broken in the black beast-bird’s morning

Call that pins the heaven to the black road.

The familiar public protest “I can’t breathe” is returned to its heartbreaking source, the moment of helplessness the mother feels for her dying son, which gives the rallying cry renewed intensity. In the book’s seamless mix of the archaic and the contemporary, the Middle English “crag” becomes the “corner store” and catchy hip-hop refrains like “we started at the bottom now we’re here” flow naturally with the wisdom of Augustine. Reeves isn’t asking himself what to take from this canon or what to leave behind. Instead, he expands literary tradition so that new political ideas, self-revelation and play can thrive.

“Sovereign Silence, or the City” is a haunting ekphrastic poem based on Vincent Valdez’s ominous painting “The City I.” In larger-than-life images, Valdez renders Klansmen huddled in a field, illuminated by the glaring lights of a pickup truck. At the center of the group, a hooded mother holds her hooded infant. This scene of intergenerational violence contrasts starkly with “Rat Among the Pines,” where the poet’s attention is turned to his young child, who already fears the police: “And my daughter hiding in the rose/Bushes, asking who, who the sirens/Have come to kill.”

While American poetry can sometimes feel uninvested in geopolitics, Reeves ties racism in America to oppression on a global scale. A poem that begins as an elegiac sonnet for the Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani (“this peace/Which is not peace but the neck after the sword, the bomb after/Blowing out all the windows”) becomes an envoi about the 1963 Birmingham church bombing — “The four dead girls who’ve been driven in and out of the poem/By history and a bomb in the basement of a church.” The last line of the sonnet (“What are you loyal to other than death?”) starts the envoi, a repetition that underscores their political connection.

What I find most moving in this collection is the way fatherhood frames Reeves’s sense of the future and his reworking of the past. His daughter becomes a generator for paradise, the underworld, utopia and dystopia. What will he leave behind for her? What can he extract from Gilgamesh or Orpheus? And is this world, on the page, from the “black spots on the rose” to the “tick-tock of crows,” enough, for now? “Black Child,” he writes in the final poem, “you are the walking-on-of-water/Without the need of an approving master./You are in a beautiful language.”

Spread the word