There are certain divides in the American electorate that we return to over and over again to explain why people think and vote the way they do. Age, gender, race, education — you know the drill. But other, harder-to-see divisions can be just as important, if not more so. Those hidden divisions aren’t about vital statistics or affiliations. They’re about how people see the world.

Take the issue of abortion. It’s been in the headlines ever since a leaked Supreme Court opinion suggested that five justices are ready to overturn Roe v. Wade, giving states the power to ban abortion for the first time in about 50 years. Plenty of speculation has focused on how such a ruling would affect female voters, particularly if it could push more women to vote for Democrats in this year’s midterm elections.

But that framing isn’t the only way to look at the issue. Even though abortion is often presented as a women’s issue, it’s not a topic with a stark division of opinion between men and women. If you dig into the polling and research, it becomes clear that the divide is less about people’s individual genders than the way they think about gender. People who believe in traditional gender roles — and perceive that those roles are increasingly being blurred to men’s disadvantage — are much likelier to oppose abortion than people who don’t hold those beliefs.

The dividing lines of the abortion debate aren’t just about the morality of terminating a pregnancy. They’re also about views of power. Who has it? Who doesn’t? And who should? And the influence of those beliefs isn’t limited to abortion — it also spills into other culture wars, particularly about whether men face discrimination.

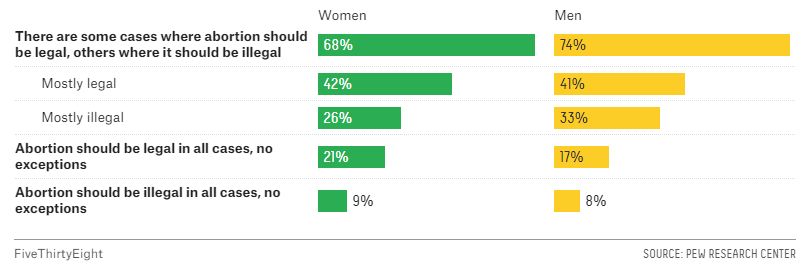

Whenever abortion is in the news, a lot of discussion inevitably hinges on how women will respond. Losing access to safe, legal abortion will mean that more women carry unwanted pregnancies. The issue itself is often framed in terms of women’s rights and autonomy. The problem is that not all women think about abortion that way. According to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center, men and women in the U.S. have exceedingly similar views about abortion’s legality.

Women and men have very similar views on abortion

Share of U.S. adults who agreed that abortion should be completely legal, completely illegal or legal in some cases but not others

The Pew poll did find that more women (40 percent) than men (30 percent) said they’ve thought “a lot” about abortion. But that doesn’t mean women’s views on the issue are more uniform. In fact, some of the most prominent anti-abortion advocates and politicians are women. One reason is that religion is a good predictor of views on abortion, and women tend to be more religious than men. Some people who oppose abortion also see it as a women’s-rights issue but in a different sense of the term — they argue that abortion hurts women.

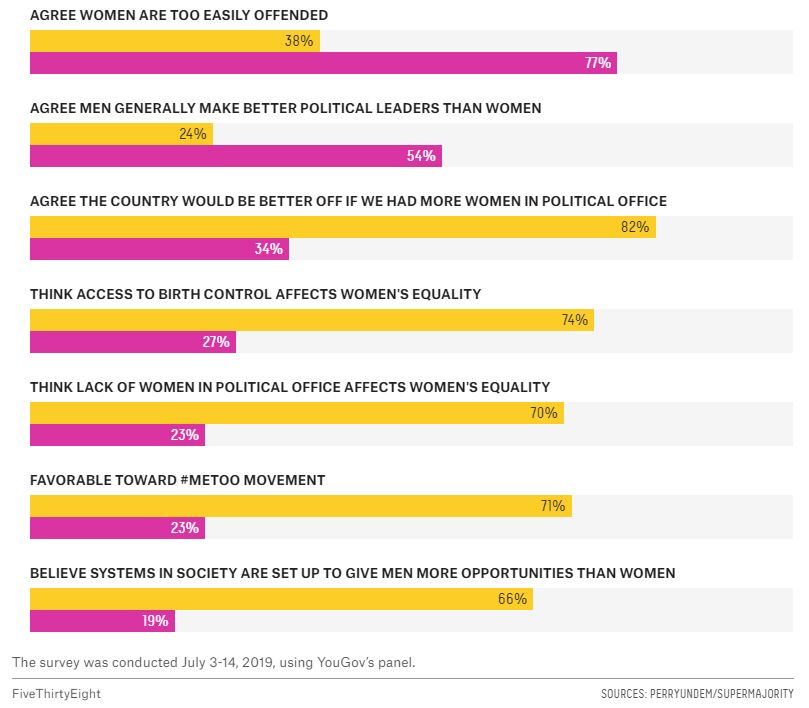

People with different views on what's needed for gender equality, it turns out, also tend to think pretty differently about abortion — at least, that’s what Tresa Undem, a co-founder of the nonpartisan research firm PerryUndem, has found. In a recent survey,1 her firm found that 69 percent of voters who want the Supreme Court to overturn Roe agreed with the statement “These days, society seems to punish men just for acting like men,” while a similar share of voters who support Roe (63 percent) disagreed. In a 2019 poll2 that PerryUndem ran in partnership with Supermajority, a left-leaning advocacy group that focuses on women as a voting bloc, they found that likely voters who oppose abortion rights were much less likely, in general, to believe that the balance of power between men and women is unequal, or that issues like birth control access and women’s political representation affects women’s equality.

Views on gender roles line up with views on abortion

A survey looked at two groups of people: likely voters who believed abortion should be legal (yellow bar) or illegal (pink bar) in at least most cases. Then the researchers looked at what percentage of each group agreed with each of the following statements …

These findings line up with decades of research suggesting that views of abortion are intimately linked to how people think about motherhood, sex and women’s social roles. In the 1980s, the sociologist Kristin Luker argued that abortion is such an intractable issue because the people on either side of the debate have fundamentally different ideas about women’s autonomy. According to her, abortion-rights supporters saw women’s ability to make decisions about their bodies as fundamental to women’s equality, while anti-abortion advocates believed this focus on autonomy undermines the importance of women’s roles as mothers.

That analysis can feel a little stuck in the Reagan era, particularly since support for women working outside the home has grown significantly since the 1980s. Tricia Bruce, a sociologist affiliated with the University of Notre Dame’s Center for the Study of Religion and Society who has researched attitudes toward abortion, said that people who oppose abortion aren’t “necessarily from a place where women belong in only one sphere, which is motherhood.” But views about power and control are still crucially important, she said. In contrast with a focus on women’s ability to make decisions about their own bodies, anti-abortion advocates see that choice within a broader context where other people have views that matter too. “We hear about women and their spouses, what’s the father’s role,” she said. “The idea is that this is not a decision that women should make in isolation.”

The divide between people who support traditional gender roles — especially those who think modern society is upsetting the balance of those roles by giving women too much power — and people who disagree with that position is spawning other culture wars. It’s partly why former President Donald Trump’s hypermasculine persona worked so well for him politically, and why Republican politicians continue to focus on the idea that men face discrimination, fueled by a backlash to the #MeToo movement and by declining rates of higher education and rising rates of loneliness among men.

These arguments don’t appeal to all men, of course, and they do appeal to some women.

Those messages tap into anxieties shared by men and women about the waning influence of traditional gender roles — in this case, traditional masculinity. Political scientists have found that when people are thinking about threats to their power and status, political behavior and attitudes change, making leaning on those anxieties a viable political strategy. For instance, in an experimental study conducted in 2016, the authors found that when men’s masculinity was threatened by the prospect of job loss, those men were more likely to say they wanted a masculine president — which, of the two candidates, was Trump.

This also helps explain why there are usually bigger political divides among men and women than between them. For example, studies find that men who adhere to more stringent notions of masculine identity, which is used as a proxy for supporting traditional gender roles, look very different on political issues than men who identify as less masculine, as we wrote in 2020. Another way to see these divides is through the lens of partisanship. According to a recent poll by the American Enterprise Institute’s Survey Center on American Life, 25 percent of Democratic men and 20 percent of Democratic women agreed with the statement “American society today has become too soft and feminine,” while 78 percent of Republican men and 65 percent of Republican women agreed with it. And just 26 percent of Democratic men and 20 percent of Democratic women agreed with the statement “White men are too often blamed for problems in American society,” compared with 75 percent of Republican men and 60 percent of Republican women.

All of this complicates the conventional political wisdom about how and why voters will respond to political changes and messaging. It’s a little pointless to ask whether women as a whole would mobilize in response to the Supreme Court overturning Roe, since women hold such wildly different views on abortion. Instead, it’s more telling to examine other facets of people’s identities — like their beliefs about gender roles — that are less visible but more politically powerful.

“Abortion is becoming personal for people who see it as a proxy for men, largely white men, taking away power from women,” Undem told us. “It’s not about a procedure. It’s about women’s place in the world.”

Meredith Conroy is an associate professor of political science at California State University, San Bernardino, and co-author of “Who Runs? The Masculine Advantage in Candidate Emergence.” @meredithconroy_

Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux is a senior writer for FiveThirtyEight. @ameliatd

FiveThirtyEight

Mission

We use data and evidence to advance public knowledge — adding certainty where we can and uncertainty where we must.

Values

The values we aspire to in our journalism …

Empiricism — We base our stories on evidence. We use many different kinds of evidence — data, reporting, first-hand experience, academic research, etc — but we also interrogate it for underlying biases.

Accuracy and completeness — Our primary standard is: “Is this accurate and does it present as complete a picture as possible?” and not some impossible “objectivity” or ideological centrism. We’re rigorous, and make every effort to test our hypotheses and assumptions. When the truth runs contrary to prevailing narratives we aren’t afraid to push back.

Transparency — We show — and share — our work. That means we explain how we reached our conclusions, and whenever possible, share the data behind our stories. It also means we acknowledge that we bring our own biases and perspectives to the work. The data does not speak for itself; we’re doing the speaking, and that requires us to think and work through how our own perspectives might influence our journalism and try to account for them.

Inclusivity — We make work that is relevant and accessible to a diverse audience. We make journalism for and about people of all identities — by race, gender, age, ability and background. We make journalism for readers, not for other journalists. And we make journalism for everyone, not just experts.

Humility — Our understanding of the world is iterative. We aren’t afraid to say, “we don’t know,” or that our old analysis is now outdated, and with new evidence our argument has changed. When we’re wrong, we say we were wrong.

Personality — Our journalists can bring their whole selves to their work. We share who we are and let the personalities of our journalists shine through.

Spread the word