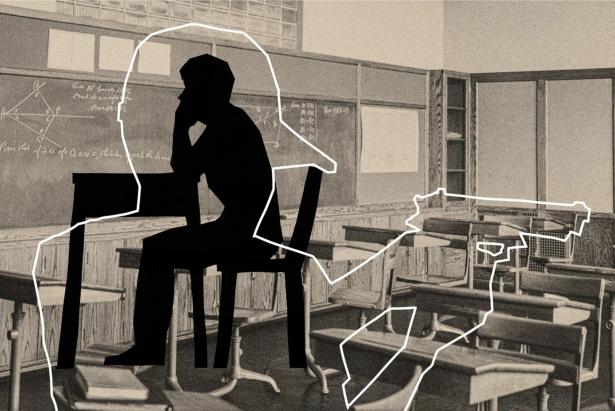

The gunman from Conklin, NY, arrested for shooting 10 Black Americans as they shopped in a Buffalo supermarket, could have been a student at my school. He might have sat in the corner desk, by the door, next to Jamal and James, across from Sara and Sabah.

Dylann Roof could have been my student. So, too, Derek Chauvin. And the 18-year-old arrested just days ago for shooting Texas schoolchildren and their teachers. (My God, how much grief can we bear in this country?) All these men were students at some point: American teenagers required by law to attend 13 years of classroom education. During that time, they studied math, science and literature, but did they ever talk about race, color and identity? Did they ever hear of a vision of an America where genuine racial justice takes hold and community overcomes division? Were they presented with history and stories of Black excellence, resilience and love?

This is not such an outlandish thing to consider. Every mass shooter, every domestic terrorist, every white supremacist was first an American student—a member of a classroom with a professional educator following a designed curriculum.

Can such teachers, schools and curriculums offer something to intentionally counteract and resist racism, bias, hatred, suffering, isolation and fear?

And now, amid a climate of raging racial backlash on the right, we have to ask an even more fundamental question: Are we allowed legally to do such work?

As it turned out, the Buffalo shooter was an advanced, master student of racist ideology; peer open into his mind and you will find a boiling mix of confusion, delusion, disgust, hatred, abuse and fear. So, so much fear. On his gun, he had reportedly written: “here’s your reparations!” He appears to have posted some 180 pages of a racist manifesto, steeped in the hateful mythologies of white replacement theory. No teenager writes 180 pages without tremendous energy, influence and emotion.

Somebody got to him. Something got to him.

Over my career, I’ve taught students who claimed allegiance to the alt-right. (The first time I ever heard of the Boogaloo Boys? My classroom. “I’m a member,” one student said.) I’ve taught grandsons of Klansmen. I’ve had daughters of bigots and granddaughters of zealots in my classrooms. Just like the rest of us, these young men and women walk into school with a lifetime of conditioning, a belief system already set into place by forces at work long before they were even born. I suffer no illusions that I am capable of changing that, nor do I write here out of self-righteous presumption that my curriculum or lessons could, in fact, heal such wounds and confusion.

Yet we must try. I teach under the mandate that education is an act of freedom, a “subversive activity,” as Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner once wrote. In the face of white supremacist violence, we as educators—especially white educators—must see ourselves as working at ground zero in the struggle to overcome the ideologies of race hatred: offering something in response, another way of encountering the world, another diet for our students’ hearts and minds.

When schools do not respond in such ways, pretending a false neutrality, they offer nothing of substance to counter racist and bigoted mindsets. They do not respond to the wolves at the door. The gag orders and book bans that outlaw critical race theory were set into motion by white legislators who, I believe, have avoided any meaningful interior racial work and are motivated by fear. So, so much fear. Their efforts to restrict anti-racist thought and speech is the equivalent of tightening a noose around one’s own neck and calling it freedom. By refusing to open up to discussions around race and color, the prison—the rigidity of fear is indeed like a prison—only gets tighter.

Every student in this country is a student of something. Every student is learning something, being taught something, being educated by something. And most of their education overwhelmingly takes place in non-classroom settings, usually online: places, such as Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, TikTok and various underground chat rooms. Every teenage pocket harbors a piece of technology far more influential than any classroom. Their phones are constantly informing, persuading, influencing, presenting, ignoring, exaggerating, dismissing, insulting. They are students of a global industry fueled by algorithms designed to addict users through disinformation, fear and scrolling sexualized endorphin-drip-drip chaos. Many of my students spend eight hours a day on their phones—roughly the same amount of time they’re required to be in school. The Buffalo gunman reportedly credits the anonymous online community 4chan as influential. In other words: it taught him something. It was his main classroom.

White anti-CRT legislators believe they can prevent discussions of race by outlawing and manipulating what’s taught in classrooms, a tactic that’s laughably tragic, almost Oedipal. American students are soaked in online memes and beliefs; yet legislators see them as a vast and undifferentiated tabula rasa, waiting to be imprinted upon. And by gatekeeping certain discussions, the guiding assumption goes, these (white) children will remain unharmed. It’s almost a new form of the white purity codes of the antebellum South. Keep them away from Blackness, and they’ll remain safely ensconced in their bubbles of white denial. It’s also delusional, like trying to outlaw jaywalking by banning streets.

At my school, a white administrator spoke to the student body in the wake of the Buffalo massacre. He called for a moment of silence and, if students wished, they could pray for peace. Yet he never mentioned race at all. The entire event was stripped of any racial meaning.

“These people were shot just because they were shopping for groceries,” he said.

From the back of the auditorium, I wanted to scream. No, that’s not why they were shot! They were shot because they were Black. They were shot because a white boy has been conditioned and taught to believe in the delusion of racism. They were shot because that is what has always happened in this country.

And now, just as they did after Nat Turner’s Rebellion, white lawmakers are trying to handcuff education. Back in 1831, they outlawed reading and writing for Black people. Now, they outlaw discussions, curriculum and conversations.

Across America, teachers are struggling: is it now illegal to discuss Buffalo? Can we even talk about it if such discussions are explicitly forbidden under our state’s anti-CRT laws? Dr. David Nurenberg, a consultant and professor at the Graduate School of Education at Lesley University, declared in Education Week that the Buffalo shooting to be the exact reason why schools must talk about race:

When white people—especially white educators—conceive of racism as an issue somehow relevant only to Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color, it’s like addressing drunk driving by talking only to pedestrians. Students of color indeed need support at times like these, but these are also precisely the times when white students, and adults, most need antiracist education. Unfortunately, these days they are less likely to receive it: 17 states, through outright legislation or other avenues, have adopted vaguely worded policies limiting teachers’ discussion of the history and present conditions of racism in the United States.

And:

With schools increasingly constrained in what they can teach, too many white people—like the 18-year-old accused Buffalo shooter—wind up receiving their education instead from racist social media communities that promote the conspiratorial “replacement” theory and other racist propaganda that portray white people as the modern victims of discrimination.

The Buffalo shooting should be a rallying call for schools to offer white students a genuine education about present-day racism and how it is not just perpetrated by gunmen but also reinforced by the unconscious everyday actions of so many of us ordinary white folk.

I spoke about this with one friend, a Black activist who regularly speaks in my classroom.

“This is a missed opportunity for empathy and connection—an opportunity to teach and dialogue and understand the real world,” he said.

As teachers, we are trying so hard, working ourselves often to the point of exhaustion. How long can we go on like this? How much can we bear?

Willie Randall is the pseudonym for an American educator who’s taught race and racial theory at multiple schools in multiple states. Student names have been changed or their experiences compiled together.

Diary of a Targeted Teacher is a recurring column featuring the experiences and reflections of an educator seeking to teach the truth about race in America in the midst of a campaign to suppress all such classroom discussions.

Founded in 1996, The African American Policy Forum (AAPF) is an innovative think tank that connects academics, activists and policy-makers to promote efforts to dismantle structural inequality. We utilize new ideas and innovative perspectives to transform public discourse and policy. We promote frameworks and strategies that address a vision of racial justice that embraces the intersections of race, gender, class, and the array of barriers that disempower those who are marginalized in society. AAPF is dedicated to advancing and expanding racial justice, gender equality, and the indivisibility of all human rights, both in the U.S. and internationally.

Spread the word