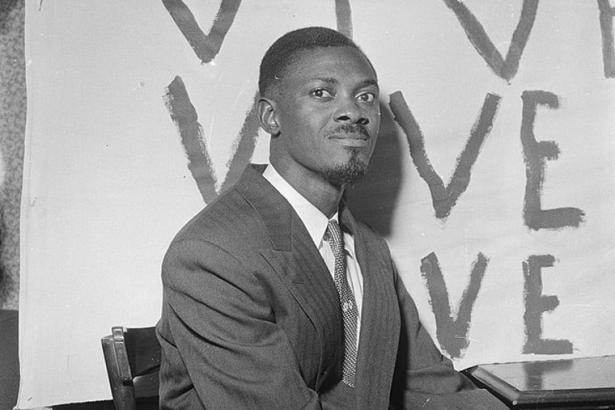

After sixty-one years, the gold tooth of the assassinated Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba has been returned to his family and laid to rest. It is the only part of him that remains.

After his brutal murder in 1961, Lumumba’s tooth was pocketed by a Belgian police officer and later held captive by the Belgian government. Its repatriation was preceded by a grotesque ‘colonial guilt’ show, in which Belgian King Phillipe expressed his ‘deepest regrets for those wounds of the past’.

The King of the Belgians did not go so far as to formally apologise, nor did he offer reparations for the devastation inflicted upon Congo by Belgium. These two events so close in proximity illustrate clearly that despite supposed ‘decolonisation’, Congo continues to be ensnared in the grasp of its colonial oppressors.

King Léopold’s Ghost

To fully appreciate the context in which the repatriation of Lumumba’s remains took place, the historical relationship of Congo with Belgian imperialism must first be understood. The ‘jewel’ of Congo was introduced to Belgian King Léopold II—the brother of King Phillipe’s great-great grandfather—by a Welsh explorer and speculator called Henry Morton Stanley. As he explored the Congo Basin he made note of and valued its bountiful resources, claiming of Ivory alone:

It may be presumed that there are about 200,000 elephants in about 15,000 herds in the Congo basin, each carrying, let us say, on an average 50 lbs. weight of ivory in his head, which would represent, when collected and sold in Europe, £5,000,000.

Unable to ignore the allure of the potential wealth offered by controlling this uncharted territory, Léopold met with Stanley in 1878 and formally employed him to begin subtly expanding Léopold’s access to the region. Stanley’s land acquisition was successful: Leo Zellig argues that by 1884, he could boast of at least ‘500 treaties’—treaties’ referring to land deeds signed unknowingly by indigenous tribes in a foreign language.

Having established a vast territory under his personal control, Léopold used these ‘treaties’ alongside benign claims of a benevolent mission to legitimise his claim to the land. When the European imperialist powers decided among themselves to carve up Africa during the 1884-5 Berlin Conference, they granted Léopold his wish, officially recognising the International African Association of the Congo (later the Congo Free State). In what was to represent a long-lasting relationship, the United States was the first nation to recognise Léopold’s claim to this land prior to the Conference, and lobbied the European powers to do the same.

Far from the humanitarian, ‘civilising mission’ that Léopold promised, his personal rule of the Congo Free State was one of the most barbarous, violent, and despotic episodes of an era already defined by unspeakable colonial brutality. Enforced at the barrel of a gun by his private mercenary army, the Force Publique, Léopold rapidly set about bleeding Congo dry in search of staggering profits. Harsh rubber, gold, and ivory quotas were imposed upon the indigenous population, with mutilation and mass killings common punishments for those who failed to meet targets.

Photographer Alice Seely Harris brought to life the horror of Léopold’s rule in the Congo Free State through her now-famous photograph of Congolese man Nsala in 1904. In the photograph, Nsala sits grief-stricken before the severed hand and foot of his five-year old daughter, Boali, who had been mutilated and killed as his punishment for failing to meet his rubber quota. When Congo’s present King Phillipe speaks of the ‘wounds of the past’, it is to heartrending episodes like this that he refers.

Nsala of Wala in Congo looks at the severed hand and foot of his five-year old daughter, 1904. (Wikimedia Commons)

Without once stepping foot in the Congo Free State, it is estimated that Léopold’s genocide massacred at least ten million Congolese from 1885 until the time he ceded control of the territory to the Belgian government in 1908. Wrought mercilessly from the bodies of the Congolese and extracted from the land, Léopold also managed to amass a fabulous personal wealth equivalent to billions of pounds today. The industrial scale of wanton violence in the Congo Free state was perhaps most famously represented in Joseph Conrad’s 1899 Heart of Darkness, which, although fictional, utilised his experiences working for a Belgian company on the Congo River.

Indigenous Congolese did not bear this brutalisation and dehumanisation passively, however. Everyday acts of resistance in the face of overwhelming violence took place, as well as several open rebellions against Léopold’s oppression. Viewed with a knowledge of this history, it is clear the gruesome murder of Patrice Lumumba, the mutilation of his body, and the collection of his tooth as a trophy were informed by a history of identical brutality meted out upon the Congolese population at large.

Lumumba Rising

Patrice Lumumba was born on 2 July 1925 in the village of Onalua, less than two decades after the Belgian Free State became the Belgian Congo. While King Leoplold no longer controlled the territory, life under Belgian colonial administrators offered little improvement. Congo’s transformation into a minor European settler colony accelerated, with the colonial authorities codifying ethnicities into statute law and enforcing segregation. The dreaded rubber quotas remained, with villagers coerced into trekking miles to tap rubber in nearby forests. Like apartheid South Africa, Congolese subjects over the age of eighteen had to carry a permit to travel around, and a 6pm curfew was imposed across the colony.

Through Catholic missionaries, Belgian colonisers sought to recreate the colonised African in their own image. The model African was known an évolué: they spoke French, dressed in European fashion, and were able to hold white-collar jobs and enter whites-only shops—the living embodiment of what Frantz Fanon would later title his 1952 publication: Black Skin, White Masks.

Lumumba was educated in a Catholic mission, witnessing first-hand how violence operated at every level under colonial rule. Whippings and beatings were common, and a regime of hard labour was imposed upon students. Over the course of his early life, Lumumba was granted the accreditation of évolué and all the benefits that came with it. After leaving school, he began work a colonial postman in Stanleyville (today Kisangani) and stayed there for over a decade.

Lumumba’s first involvement with colonial politics came in 1955, when he joined the Belgian Liberal Party—but his opposition to the Catholic church and refusal to defer to Belgian colonisers soon led to significant opposition to his presence. On 6 July 1956, Lumumba was arrested for embezzlement, beginning the slow process of his radicalisation against Belgian colonialism. Upon his release in 1957, Lumumba was no longer a moderate évolué but a radical anti-colonial independence agitator.

In 1958, Lumumba helped establish the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), and was elected president upon its founding. As MNC president, he attended the first African conference of Independence States held by President of the newly independent Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah. At the Conference, Lumumba stressed the need for Pan-African unity:

This historical conference which brings us in contact with qualified leaders of all the African countries and the entire world, reveals one thing to us: In spite of the frontiers that separate us, in spite of our ethnic difference, we have the same conscience, the same soul which bathes day and night in anguish, the same wish to make the African continent independent … free of uncertainty, fear of colonial domination.

If Lumumba’s stint in prison marked the beginning of his radicalisation, his meeting with Nkrumah and other Pan-African, Chinese, and Soviet delegates in Ghana was the catalysing force. Carrying home the momentum and optimism of the conference, Lumumba returned to Congo re-energised and threw himself into anti-colonial organising.

1960: Lumumba holds up his wrists, injured by handcuffs, after his release from hail where he had faced charges of inciting an anti-colonial riot.

A watershed moment for Lumumba and the MNC arrived during an uprising in the capital of Léopoldville on 4 January 1959, which led to an estimated 500 Congolese deaths. The MNC became the de-facto sole political operator in the city, dramatically raising its profile. The uprising also had the effect of radicalising the urban population, with the MNC providing an attractive alternative to life within the Belgian colonial system. Other, more explicitly radical parties such as the Action Socialiste the Party of the People (established by former MNC founder Alphonse Nguvulu) and Parti Solidaire Africain (PSA) also held significant sway over the évolué population.

The irreconcilable contradictions of life under colonial rule were fast coming to a head, and in March 1959 Lumumba, tired of the Belgian authorities dragging their feet, demanded a date for Congolese independence. Lumumba was a tireless advocate, reportedly working eighteen-hour days to spread his message until he was arrested for a second time in October and sentenced to sixth months’ imprisonment in January.

Lumumba’s second imprisonment further raised his profile; within mere days of his release, 30 June 1960 was scheduled to be the day of independence at the Congolese Round Table Conference in Brussels. By 23 June, Lumumba’s MNC had won a plurality of thirty-three seats and was able to establish a coalition government. An independent Congo was born a week later.

In a visit echoed by his descendant King Phillipe, Belgian King Badouin gave an Independence Day speech where he commended the ‘genius of King Léopold II’ and called for his newly independent subjects to ‘show that you are worthy of our confidence’.

In one of the most defining moments of his career, Lumumba—not originally scheduled to speak—delivered an excoriating denunciation of Belgian colonialism before the Belgian King and his fellow Congolese. The speech was received with widespread applause from the Congolese audience, but incensed King Badouin, who threatened to leave the event. While Lumumba’s growing association with the Soviet Union and talk of resource nationalisation had painted a target on his back, it was this affront to global white supremacy that sealed his fate.

The Katanga Plan

With tensions between Belgium and Congo inflamed and Western powers growing fearful of losing the resource-rich country to the Soviet Union, a plan was hatched to remove Lumumba from the picture permanently.

Following the outbreak of violence after Lumumba’s ‘africanisation’ of the military (by replacing European officers with Africans), Katanga Province—which held much of Congo’s mineral deposits—declared its succession from Congo, backed by the Belgian government and Belgian mining companies on 11 July 1960. Belgium sent troops to the region ostensibly to protect Belgian nationals and capital, but the troops were secretly aiding the rebels.

Lumumba pleaded with the UN to intervene to contain the rebellion, but his calls fell on deaf ears. Unable to secure help from the UN, Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union for aid, in an act that signed his death warrant.

Lumumba’s arrest on 2 December came as part of a joint operation between MI6, the CIA, and Belgian intelligence forces. Betrayed by one of his former allies, Joseph Mobutu, Lumumba’s execution was a gruesome affair. Along with his close allies Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, Lumumba was stood against a tree and shot, their bodies dismembered and dissolved in acid. As a reward for his collaboration, US-asset Mobutu went on to rule Congo for over thirty-two years as a brutal dictator.

Lumumba Lives

It has taken over six decades for Belgium to repatriate Lumumba’s tooth, and in the time since, the nation of Congo has become synonymous with brutality, conflict, and instability. To this day, Belgium refuses to officially apologise or offer reparations for the unquantifiable destruction it has wrought in Congo, and statues dedicated to the ‘genius’ of King Léopold II remain proudly standing in public spaces.

In 2002, a Belgian parliamentary investigation concluded that Belgium was ‘morally responsible’ for Lumumba’s death. This means little while they retain the air of colonial master, glorifying their blood-soaked past and continuing to take part in the underdevelopment of Congo.

It is impossible to say what Congo would have looked like under Lumumba, as he was assassinated a mere three months into power. Nonetheless, his martyrdom has elevated him into a symbol of anti-colonial resistance worldwide, and the name ‘Lumumba’ sits among his similarly-deposed contemporaries such as Kwame Nkrumah, evoking thoughts of what could have been. Now, with Lumumba finally laid to rest, he continues to inspire those dedicated to global equality and anti-imperialist struggle today.

Perry Blankson is a Tribune columnist and a project coordinator at the Young Historians Project. He is a member of the Editorial Working Group for the History Matters Journal.

Tribune was established in 1937 as a socialist magazine that would give voice to the popular front campaigns against the rising tide of fascism in Europe. For eighty years it has been at the heart of left-wing politics in Britain, counting giants of the labour movement like Aneurin Bevan and Michael Foot among its former editors.

Tribune was relaunched as a print magazine and website with the support of Jacobin in 2018, and its new team is committed to reviving this great tradition on the British left. Our mission remains, as Michael Foot wrote on the magazine’s 21st birthday, “to sustain the old cause with the old weapons.”

Spread the word