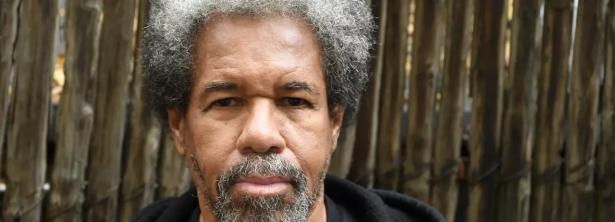

Albert Woodfox, a wrongfully imprisoned Black Panther activist who spent his 43 years in solitary confinement uplifting himself and others before finally being freed in 2019, died Thursday of complications from Covid-19 at age 75.

"With heavy hearts, we write to share that our partner, brother, father, grandfather, comrade, and friend, Albert Woodfox, passed away this morning," Woodfox's family said in a statement. "Whether you know him as Fox, Shaka, Cinque, or Albert—he knew you as family. Please know that your care, compassion, friendship, love, and support have sustained Albert, and comforted him."

The family added that Woodfox was a "liberator" who inspired Americans to "think more deeply about mass incarceration, prison abuse, and racial injustice."

Civil rights attorney and former NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund president Sherrilyn Ifill called Woodfox "one of the most extraordinary human beings I've ever met."

"He deserved more time to experience his freedom, but what he did with time he had was transformative," she tweeted. "May he rest in eternal peace and power."

Born February 19, 1947 in New Orleans, Woodfox—the oldest of six siblings—admitted to choosing the wrong path in his youth.

"I robbed people, scared them, threatened them, intimidated them. I stole from people who had almost nothing," he wrote in 2019. "My people. Black people."

In 1971, Woodfox was serving a 50-year sentence for armed robbery at the notorious Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, a former slave plantation then known as one of America's toughest prisons. That year, he and fellow inmates Herman Wallace and Robert King formed a chapter of the Black Panthers to combat the rampant rape and sex trafficking, violence, and horrific living conditions at the prison. They organized strikes and sit-downs, earning the respect of many of the prison's Black inmates and raising the ire of racist prison officials.

"Our cells were meant to be death chambers but we turned them into schools, into debate halls," Woodfox told The Guardian after his release in 2019. "We used the time to develop the tools that we needed to survive, to be part of society and humanity, rather than becoming bitter and angry and consumed by a thirst for revenge."

On April 17, 1972, Angola guard Brent Miller was stabbed to death at the prison. Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Robert King—the Angola Three—were immediately charged with the killing and locked up in solitary confinement.

Woodfox was tried and convicted twice for Miller's murder but courts later overturned both convictions. A judge ruled in 2008 that Woodfox was denied due process, citing ineffective legal counsel and questionable evidence in his trials. Woodfox's lawyers also successfully argued that their client's conviction was literally bought by the state, whose case relied heavily upon the testimony of jailhouse informants rewarded for their cooperation.

Woodfox always maintained his innocence, claiming he was wrongfully punished for Miller's murder because of his political activism.

"We dared to resist," he told The Washington Post. "We were very influential."

For four decades, Woodfox would spend 23 hours a day alone in a 6-by-9 foot cell. He read Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Nelson Mandela and inspired other inmates to read and fight for their rights.

"We saw some things that was amiss, in prison and out of prison," Robert King told Democracy Now's Amy Goodman in a Friday interview. "And we decided that we could add our little pebble to the pond. And so, Albert... threw the pebble in the pond, knowing that it would create a ripple and knowing that it would eventually create a tsunamic effect... The pebble that he threw in the pond became a ripple, became a wave. And so, this will carry him on into eternity. He won't be forgotten."

In 2008 U.S. District Judge James Brady reversed and vacated Woodfox's conviction and life sentence. However, Louisiana's attorney general at the time, James "Buddy" Caldwell, appealed the ruling to the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, which found Brady had acted erroneously.

"I do not have the words to convey the years of mental, emotional, and physical torture I have endured," Woodfox wrote to supporters in 2013. "I ask that for a moment you imagine yourself standing at the edge of nothingness, looking at emptiness. The pain and suffering this isolation causes go beyond mere description."

Legions of lawyers and laypeople, activists, celebrities, and international organizations and individuals rallied behind the Angola Three. King, who spent 29 years in solitary confinement, was freed in 2001 after his conviction was overturned. Wallace was released in October 2013 following more than 41 years in solitary after a federal court ruled he had not received a fair trial. He died three days after leaving prison.

Woodfox, who would have to wait over two more years for his freedom, raised his fist triumphantly as he walked out of prison on February 9, 2016. After 44 years and 10 months behind bars, his spirit was unbroken.

"I can honestly say I've never ever thought of giving up," he told the Innocence Project in 2021. "It never ever came close to breaking my spirit. And that's what solitary confinement is designed for… to break people."

"One of my inspirations was Mr. Nelson Mandela," Woodfox told Democracy Now! days after his release, referring to the South African racial justice activist who spent years of his 27-year imprisonment in solitary confinement before being freed and subsequently elected the country's first post-apartheid president. "You know, I learned from him that if a cause was noble, you could carry the weight of the world on your shoulder."

After his release, Woodfox wrote and published a book, Solitary, a Pulitzer Prize finalist that focused worldwide attention on the practice of prolonged solitary confinement, which is widely recognized as a form of torture. More than 80,000 men, women, and children locked up in U.S. prisons and jails are currently believed to be held in solitary confinement.

Woodfox filled the few years of freedom he enjoyed with activism, educating people in the United States and beyond about the fundamentally flawed U.S. carceral system. He remained an eternal optimist.

"I think what I went through has made me a better man, a better human being," he told the Post. "I've been asked a lot: 'What would I change in my life?' And people are surprised when I say, 'Absolutely nothing.'"

Common Dreams

We've had enough. The 1% own and operate the corporate media. They are doing everything they can to defend the status quo, squash dissent and protect the wealthy and the powerful. The Common Dreams media model is different. We cover the news that matters to the 99%. Our mission? To inform. To inspire. To ignite change for the common good. How? Nonprofit. Independent. Reader-supported. Free to read. Free to republish. Free to share. With no advertising. No paywalls. No selling of your data. Thousands of small donations fund our newsroom and allow us to continue publishing. Can you chip in? We can't do it without you. Thank you.

Spread the word