It’s interesting to see how political art changes. This year’s Whitney Biennial, rather than in-your-face commentary on American injustice here and abroad (including at the 2019 biennial black football players taking the knee), my favorites here were more subtle takes, one on the consumer culture, another on the military and a third that rivets your eyes on U.S. corporate destruction abroad.

Then there was a collection that I thought was a parody, but discovered it was serious: a series of questions on becoming an American that people who take citizenship tests must answer.

The Zombies: Walmart, Apple, Disney. “La horda” (The horde) 2020.

Andrew Roberts, born 1995 in Tijuana, who lives in Mexico City and Tijuana, did a video installation about allegorical zombies, victims of what he calls “a crossfire geopolitical war.” The heads move and they speak.

Roberts explains he is reflecting on the deleterious effect of NAFTA, set up to provide cheap labor to American factory owners and destroy jobs of Americans. (The Economic Policy Institute reports that “an exploding deficit in net exports with Mexico and Canada has eliminated 394,835 U.S. jobs since NAFTA took effect in 1994, contributing significantly to the 4% decline in real median wages since 1993.”) Roberts says the U.S. sent Mexico American TV reruns and turned Tijuana into a distribution point for illegal arms and drugs. He says his childhood cartoons were mixed with the brutality shown on the news.

The Big Guns support U.S. invasions.

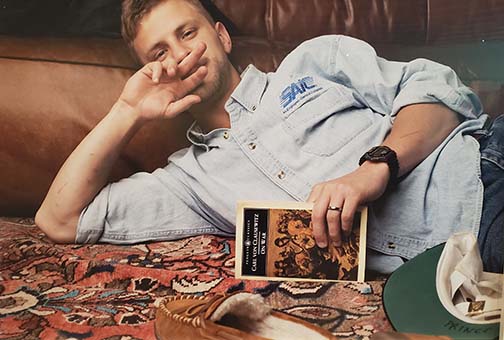

While small-time guns shot up Mexico, the big versions were meant for U.S. supported operations abroad, where well-connected mercenaries were stand-ins for the U.S. Military. Buck Ellison, born in 1987 in San Francisco, living in Los Angeles, imagines Erik Prince, founder of private security firm Blackwater (ie mercenaries) as he could have appeared on his Wyoming ranch in 2003, the year his company got its first U.S. contracts to engage in wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Prince (portrayed by an actor) is reading Clausewitz’s “On War” and looking boyish and naïve in a style designed for advertising. Appropriate, since that’s how U.S. wars are marketed to the public.

Destroying Brazilian Rainforest: “Felled jungle ready for burning.”

Most American destruction around the world has been carried out by corporations. Danielle Dean, born 1981 in Huntsville, Ala, now lives in Los Angeles and San Diego. Her watercolor and related video are based on Ford Company advertisements: “Felled jungle ready for burning.” Ford created Fordlandia in the Brazilian Rainforest in the 1920s to extract rubber there. She says, “Fordlandia essentially tried to bring the principles of the assembly line into the rainforest, with disastrous environmental and social consequences.” You can see the devastation.

Becoming American: the catechism

Then, in some ways, an unforgettable part of the exhibit. They are easy to miss, but scattered around the museum. on walls, glass windows, even above the bar and in the coat room, are bold questions from a real government civics quiz.

The installation is by Rayyane Tabet, born in 1983 in Beirut, living in Beirut and San Francisco. His questions come from the U.S. naturalization exam which he was preparing to take. “100 Civics Questions,” part of a series “Becoming American,” he said the lines “could be read like concrete poetry or open-ended, contradictory, and often hermetic questions.” Not a hint of the dripping irony they represent.

Imagining what the artists above would think, I’ve set down how they might answer the questions.

Q: Who lived in America before the Europeans arrived?

A: The Native Americans, who were largely slaughtered in America’s first genocide.

Q: What did the Declaration of Independence do?

A: Proclaimed separation from England so that white male landowners could control the new country, rule over women, poor whites and the surviving Native Americans and maintain the slavery of blacks.

Q: Name one U.S. territory.

A: It’s not something Americans are told much about since the people living there were victims of American conquest, which would later be called imperialism.

Q: During the Cold War, what was the main concern of the United States?

A: That the Soviet Union would challenge American hegemony. Global dominance is still the policy, but change the challengers to Russia and China.

Q: What is the political party of the president now?

A: It is the Democratic wing of the Corporate/Wall Street Party. It alternates with the Republican wing in America’s one-party state.

Q: What stops one branch of government from becoming too powerful?

A: The ruling oligarchy and its military industrial complex, which are more powerful than the official branches of government.

Q: The idea of self-government is in the first three words of the Constitution. What are those words?

A: Refer to previous answer. “We the people” is a nice slogan but doesn’t now and never did apply to the U.S. government.

Political scientists Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern conclude that the U.S. is a corrupt oligarchy where ordinary voters don’t count.

Gilens and Page looked at 1,779 policy issues. They found that economic elites and groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no influence. In fact, their impact was too small to count. Welcome to the American oligarchy. See the 2014 study.

Maybe the next Whitney Biennial could have questions that reflect how the oligarchy developed.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept. 99 Gansevoort St, NYC. Visit info. Tickets. April 6–Sept 5, 2022.

Photos by Lucy Komisar.

[Lucy Komisar articles have appeared in publications as diverse as The Nation magazine and the Wall Street Journal. She is also a theater critic and member of The Drama Desk, the organization of New York theater critics, writers and editors. Her particular interest is the political aspects of theater. Her interviews and programs on YouTube.

In 1962-3 was editor of the Mississippi Free Press. Her work for civil rights is described in a book on the 1960s movement, We Are Not Afraid. And in the University of Southern Mississippi archive.

We Believed We Were Immortal, a book published in 2017 by Kathleen W. Wickham, a professor of journalism at the University of Mississippi, about journalists working in Mississippi during civil rights movement, features a section on Lucy.

In 1970-71, she was a national vice president of the National Organization for Women. A major NOW accomplishment she organized was getting the government to adopt goals and timetables for hiring women by federal contractors and by radio & TV stations regulated by the FCC.]

Thanks to the author for sending this to Portside.

Spread the word