Inside the Justice Department’s Decision on Whether To Charge Trump in Mar-a-Lago Case

In February, a week before the National Archives warned the Justice Department that former President Donald Trump had kept Top Secret documents at his Florida compound, Asia Janay Lavarello was sentenced to three months in prison. She had pleaded guilty to taking classified records home from her job as an executive assistant at the U.S. military’s command in Hawaii.

“Government employees authorized to access classified information should face imprisonment if they misuse that authority in violation of criminal law,” said Hawaii U.S. Attorney Claire Connors, who did not accuse Lavarello of showing anyone the documents. “Such breaches of national security are serious violations … and we will pursue them.”

Cases like Lavarello’s are a major part of the calculus for Justice Department officials as they decide whether to move forward with charges against the former president over the classified documents found in his Florida home, current and former Justice Department officials tell NBC News. In another example, a prosecutor advising the Mar-a-Lago team, David Raskin, just last week negotiated a felony guilty plea from an FBI analyst in Kansas City, who admitted talking home 386 classified documents over 12 years. She faces up to 10 years in prison.

A charging decision may be looming as the Mar-a-Lago investigation enters what appears to be a decisive phase.

People familiar with the deliberations of Attorney General Merrick Garland and his top aides say the AG does not believe it’s his job to consider the political or social ramifications of indicting a former president, including the potential for violent backlash. The main factors in his decision, these people say, are whether the facts and the law support a successful prosecution — and whether anyone else who had done what Trump is accused of doing would have been prosecuted. The sources say Justice Department officials are looking carefully at a cross section of past cases involving the mishandling of classified material.

Garland himself previewed his approach in a July interview with "NBC Nightly News" anchor Lester Holt. Though his comments were about the separate Jan. 6 investigation, Justice Department officials said they apply broadly.

Holt prefaced a question by saying that “the indictment of a former president, of a perhaps candidate for president, would arguably tear the country apart. Is that your concern, as you make your decision down the road here, do you have to think about things like that?”

Garland answered, “We pursue justice without fear or favor.”

And when Holt asked whether Trump becoming a candidate would affect the decision-making, Garland simply repeated that the Justice Department intended to hold anyone guilty of crimes accountable.

Experts say the public evidence in the Mar-a-Lago case seems unambiguous.

“If Trump were anyone else, he would have already faced a likely indictment,” said Bradley Moss, a lawyer who often represents intelligence agency employees in cases involving classified information.

“It would be entirely outside of the rule of law to not indict him,” said former federal prosecutor Andrew Weissmann, an NBC News contributor who played a key role in special counsel Robert Mueller’s Russia probe. “The whole point is to treat people similarly. And when you look at past cases, it compels that you have to bring a case.”

Former prosecutors with experience in cases involving classified information say that based on the public information alone, the Justice Department has enough evidence to charge Trump with the mishandling of national defense information. Less clear is whether there are aggravating factors — such as whether the Justice Department can prove Trump obstructed justice by failing to turn over documents despite a grand jury subpoena.

The addition of Raskin, an experienced former terrorism prosecutor, and David Rody, another veteran prosecutor who left a law firm partnership to join the investigation, is widely seen as an effort to beef up the prosecution team in the event the case goes to trial.

“The National Security Division doesn’t try a lot of cases like this — they would want to bring in trial lawyers,” said Joyce Vance, a former U.S. Attorney and an NBC News contributor. “It looks to me like they are building a trial team.”

Amid reports that Justice Department officials are considering whether to name a special prosecutor if Trump declares his candidacy for president, some observers say that would be a bad idea.

“To me that seems idiotic,” said David Laufman, who led the Justice Department’s Counterintelligence and Export Control Section, a position now held by Jay Bratt, a key figure in the investigation of the Mar-a-Lago case.

“It’s precisely in cases like this where so much is on the line for the Department of Justice that it’s critical for DOJ leaders to participate in discussions on whether to approve charges,” Laufman said. “They should have the opportunities to kick the tires hard and as often as possible, and ultimately they should own the decision to approve or disapprove for the first time in American history potential criminal charges against a former president.”

He added, “It’s already baked in that there will be criticism … and the idea that relegating this to a special counsel will somehow mitigate or neutralize criticism from the far-right is ludicrous. Just own it. That’s why you’re in those jobs.”

Moss agreed, adding, “I really don’t think a special counsel helps anything here. I think all that does is delay things and bogs things down. There is nobody who could take the job and not be dragged through the mud.”

Not everyone believes that a prosecution of Trump is warranted, based on the known facts. One former U.S. attorney, a Trump critic, said a mere documents mishandling case is not serious enough to merit charging a former president, unless prosecutors can prove aggravating factors such as intent to share the material, or obstruction of justice.

“I think it’s a relatively minor case, and I don’t think you bring a minor case against a former president,” that person said.

Yet there are currently people serving long prison sentences for doing exactly what Trump appears to have done — taken highly classified information home, with no allegation that they gave it to an adversary.

One of them is Nghia Hoang Pho, 72, who pleaded guilty in 2017 to taking highly classified material from his job as a programmer for an elite hacking unit of the National Security Agency. At sentencing he told the judge he did it so he could work from home and earn a promotion before his retirement.

Prosecutors didn’t contest that claim, but another factor made the case much more serious. Unluckily for Pho, he had been using an anti-virus product made by a Russian cybersecurity firm, Kaspersky, which copied some of the highly classified material off of his home computer without his knowledge. U.S. officials determined that the files were handed over to the Russian government, leading to one of the worst intelligence losses in modern U.S. history. The Kaspersky firm denied giving the files to the Russian government.

Pho “compromised some of our country’s most closely held types of intelligence and forced the NSA to abandon important initiatives to protect itself and its operational capabilities at a great economic and operational cost,” Maryland U.S. Attorney Robert Hur said at the time.

Pho got five years in prison.

A former NSA contractor, Harold Martin, was sentenced in 2019 after prosecutors said he took home at least 50 terabytes of data — the equivalent of 500 million pages of mostly highly classified material — over 20 years.

Martin’s lawyers said he was a hoarder, and prosecutors concluded that he had not given classified information to anyone.

He got nine years.

Legal experts say it’s difficult to compare those two cases with that of the former president. A closer analogy, they say, would be the prosecution of David Petraeus, the retired Army general and former CIA director, who pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor after admitting giving classified material to his biographer, with whom he was having an affair, and lied to FBI agents who questioned him about it. He was sentenced to two years of probation and fined $100,000.

In a somewhat similar case, former CIA Director John Deutch was pardoned by President Bill Clinton in 2001 as he was poised to plead guilty to a misdemeanor for keeping top secret codeword information on computers at his homes in Maryland and Massachusetts.

But few can envision Trump agreeing to admit guilt, as those men did.

Among the factors the Justice Department weighs in whether to pursue classified-document mishandling cases, former prosecutors say, is whether the person knew the material included state secrets; whether they planned to profit from the information; whether they told the truth to investigators; and the volume and importance of the classified material.

Prosecutors have put no evidence on the public record suggesting Trump had any nefarious intent in keeping the classified documents, but their court filings suggest his case meets the other three criteria.

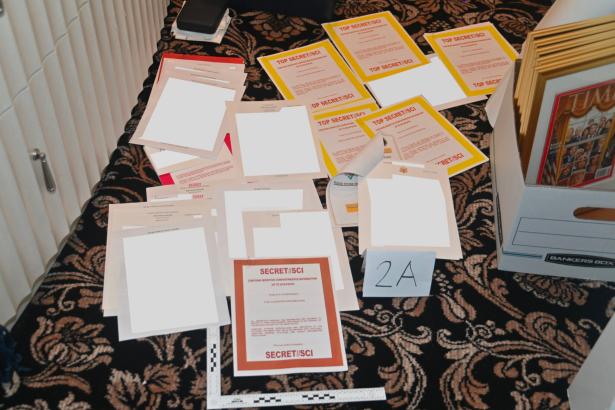

According to court filings, the National Archives put Trump on notice that they had received highly classified material from Mar-a-Lago and suspected there was more there; a Trump lawyer told the Justice Department all the secret records had been turned over, when that was not true; and some of the documents seized at Mar-a-Lago were so sensitive that only a small number of people inside the U.S. government would be authorized to see them. The FBI seized more than 11,000 documents from Mar-a-Lago, including several hundred marked classified.

“The reason he will almost certainly be indicted, in my view, is because of his efforts to obstruct and conceal the documents and prevent the government from recovering them," said Moss.

A Trump spokesman did not respond to a request for comment. Trump has called the investigation illegitimate, and his lawyers have likened it to a document dispute akin to the late return of an overdue library book.

Even if the Justice Department decides charges against Trump in the Mar-a-Lago case are warranted, prosecutors will have to clear another hurdle: securing agreement from intelligence agencies about using some of the classified information found at Trump’s home in open court.

It’s not uncommon for the government to decide against moving forward with an otherwise winnable case because officials conclude that they can’t risk exposing the intelligence information in court, according to Laufman. NBC News has confirmed that among the documents found at Mar-a-Lago are highly classified materials related to China and Iran — information unlikely to be deemed suitable for public airing.

“They need to get the intelligence community to play ball,” Laufman said, “and that means getting whatever agency owns the information to agree to their use of their classified documents in furtherance of the government prosecution.”

As for the broader social and political implications of indicting Trump, Moss said that if the Justice Department doesn’t consider them, someone in the Biden administration should.

“I would be surprised if on some level political ramifications don’t get considered and addressed,” he said. “It is a former president, a likely opponent for the incumbent president in 2024, and there has never been an indictment in this context before. Those are not trivial considerations.”

Ken Dilanian is the justice and intelligence correspondent for NBC News, based in Washington.

Spread the word