Today, Western media reports frequently present Guinea-Bissau as a “failed state” with a “narco-economy.” These disparaging labels strip the country out of its context in the global economic system and erase the legacy of European colonialism and the Cold War, giving the false impression that its problems are self-generated.

By looking at the international dimensions of Guinea-Bissau’s history, we can counter such misleading views and shed light on an anti-imperialist revolution that had a major impact well beyond this comparatively small West African territory. The revolutionary struggle launched by the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano para a Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde or PAIGC) not only led to the independence of Guinea-Bissau itself. It also made a vital contribution to the demise of Portuguese colonialism throughout Africa and the fall of Portugal’s own long-entrenched dictatorship.

This in turn had decisive consequences for the coming of democracy in Spain and South Africa alike. These two countries with a combined population of well over a hundred million people today owe a considerable debt to Guinea-Bissau, which has a population of two million. Branding Guinea-Bissau as a “failed state” erases the outsized contribution it has made to the modern world.

Cabral and the PAIGC

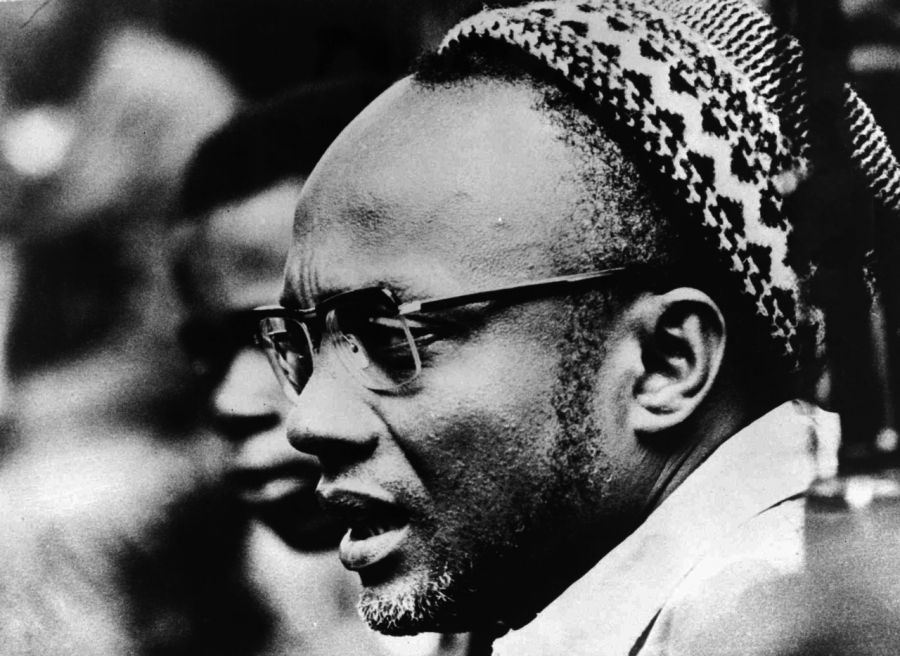

Amílcar Cabral was the founding leader of the PAIGC, which waged a successful guerrilla war against Portuguese rule between 1963 and 1974. Born in 1924, Cabral distinguished himself as a brilliant student and was one of very few Africans to attend university in Portugal, where he trained as an agronomist.

The Portuguese authorities expected men like Cabral to serve as junior colonial administrators, facilitating the exploitation of their own people. But he used his time in Portugal to forge ties with students from other African colonies such as Angola and Mozambique, some of whom would go on to play leading roles in their own independence movements. He also made contact with Portugal’s left-wing opposition currents, most notably the Portuguese Communist Party.

On returning to Guinea-Bissau, Cabral was officially employed to carry out an agricultural survey of the country for the Portuguese state. However, he used the survey as an opportunity to learn about social and geographical conditions in different regions — a base of knowledge that was essential for the coming struggle. Cabral and his comrades established the PAIGC, and after a massacre of striking dock workers by Portuguese security forces at the port of Bissau in 1959, they decided that nonviolent resistance was no longer sufficient and began preparing for a campaign of guerrilla warfare against Portuguese rule.

The Anti-Colonial Moment

The anti-colonial liberation struggles in Africa and Asia profoundly shaped the global history of the twentieth century. Liberation movements from the Global South played a key role in the emergence of a novel world order. They also empowered the colonized peoples and led to the rise of new postcolonial states in international forums.

In his writings and speeches, Cabral stressed the importance of the fight against colonial domination for world politics:

The people’s struggle for national liberation and independence from imperialist rule has become a driving force of progress for humanity. It undoubtedly constitutes one of the essential characteristics of contemporary history.

Although they defined their goal as national self-determination, we should understand these movements in terms of a more inclusive, global perspective, taking account of all the connections and interactions that shaped them at local, regional, and international levels.

The liberation project of the PAICG went beyond nationalist concerns. It identified itself as a revolutionary party that was working toward the creation of a new society, starting with the organization of a new education system, economy, and structure of health provision in the so-called liberated areas of Guinea-Bissau (the areas which were no longer under Portuguese control).

The PAIGC was fighting for the independence of not one but two colonies: Guinea-Bissau on the West African mainland and the archipelago of Cape Verde. Cabral argued that any project for liberation which did not encompass these islands would undermine the fight for Guinean independence, since Portugal and its allies could use Cape Verde as a military support base from which to launch a counteroffensive.

Amílcar Cabral, February 1964. (Wikimedia Commons)

Cabral himself had been born in Guinea-Bissau to Cape Verdean parents. He also grounded the unitary, binational project of the PAIGC in cultural and historical factors. Ever since the beginning of Portuguese colonization from 1462 onward, the colonizers had populated Cape Verde with enslaved peoples from the Guinean African coast. This meant that their peoples shared common origins.

In practice, the independence war only took place on the territory of Guinea-Bissau, as the PAIGC found it too challenging to launch an insurgency on Cape Verde. However, the liberation movement also included Cape Verdean guerrilla fighters.

Portugal and the World System

From the early 1960s, the PAIGC campaigned on the international stage against Portuguese colonialism, courting the support of governments as well as non-state allies. The Portuguese dictatorship, whose origins harkened back to interwar European fascism, was now firmly integrated in the US-led Western bloc during the Cold War, and it had been a founding member of NATO. It systematically rejected any demands for independence and fought protracted wars in three of its African colonies: Angola (from 1961), Guinea-Bissau (from 1963), and Mozambique (from 1964).

The PAIGC developed networks with the liberation movements from the other Portuguese colonies, Mozambique’s FRELIMO and the MPLA in Angola. It also took part in various pan-African and Third World initiatives. Cabral’s party gathered material, technical, and diplomatic aid for its armed struggle while spreading its analysis of Portuguese colonialism and the wider imperialist system that sustained Portugal’s wars.

By depicting Portuguese colonialism as merely the tip of a much larger complex of Western economic and political domination, the PAIGC projected its cause onto a global level. It vociferously denounced the growing investment by Western companies in the Portuguese colonies and the supply of military materiel and diplomatic cover to the Portuguese dictatorship by some of its NATO allies — particularly the United States, the UK, France, and West Germany.

This message struck a chord with states across Africa and the wider world, through international forums such as the Organization of African Unity, the Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and the UN Special Committee on Decolonization. Such discussions linked anti-colonialism to a broader critique of capitalist interests.

The Weapon of Theory

At the same time, Cabral exposed the role of the Cold War system in perpetuating colonialism. He defended a form of nonaligned anti-imperialism that challenged the geopolitical division of the world and sought to mobilize possible allies across the “iron curtain.”

The PAIGC obtained much military and political support from the Soviet bloc and from Third World allies — most notably Cuba, which sent both doctors and soldiers to assist its struggle. Yet it also received substantial aid from governments in Scandinavia and the Netherlands, whose material contributions enabled the state-building process that was taking place in the liberated areas.

We should not underestimate the impact of the struggle in Guinea-Bissau on Western civil society. There were many solidarity networks forged in Western Europe and North America to support the liberation of the Portuguese colonies. A range of sympathizers, from the US Black Panthers to activists of the French New Left, embraced Cabral’s notion of connected struggles, which argued that imperialism was a common enemy of the liberation movements and of the international working class.

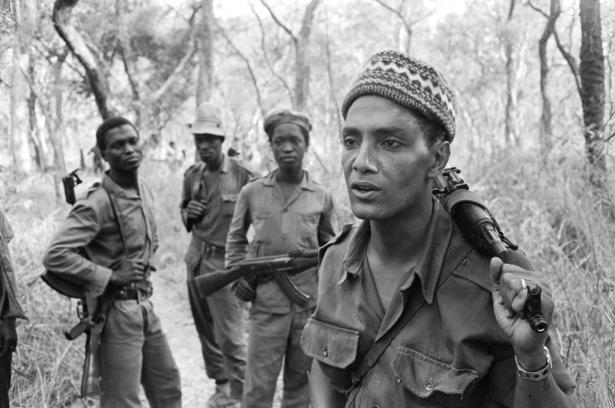

They supplied the PAIGC with political and material assistance, such as blood donations, medical aid, and school supplies for the liberated areas, while publicizing Portuguese atrocities and the complicity of Western companies and governments. Writers, journalists, filmmakers, and photographers from different countries traveled to Guinea-Bissau and reported on the experience of the population in the liberated zones.

The image of these regions that were ruled by PAIGC guerrillas played a vital role in legitimizing the Guinean anti-colonial revolution at an international level. In a wider perspective, these solidarity initiatives integrated the PAIGC’s struggle into the global emancipatory movement of the so-called “Long 1960s,” while also fostering new transnational networks and practices of protest and cooperation.

Cabral became an inspirational figure well beyond the Portuguese-speaking countries, both before and after his assassination in January 1973. Indeed, he remains a reference point for anti-colonial thinkers to this day.

This is not least because of the original way Cabral engaged with Marxist ideas, especially in the famous “Weapon of Theory” speech he delivered at 1966’s Tricontinental Conference in Havana, which made a favorable impression on the Cuban leader Fidel Castro. Many of his writings and speeches, which dealt with issues of culture, race, colonialism, agriculture, and the liberation struggle, were translated into languages such as English, French, and Spanish.

Cabral’s heterogenous, multifaceted ideas drew upon his evolving assessments of the liberation trail, and they continue to stimulate productive discussions and reflections. Scholars and activists from various disciplines and currents have placed his intellectual contributions in the context of debates about the African black radical tradition, Pan-African history, decolonial thought, and revolutionary politics, among others. One recent essay has even reinterpreted his initial scientific work as an agronomist in a progressive light.

An International Struggle

In 1964, the French writer Gérard Chaliand published the first book for a Western audience about the struggle in Guinea-Bissau. After a visit to the country in 1966–67, he went on to write influential accounts of conditions in the liberated areas. According to Chaliand, the PAIGC led the most significant armed struggle in Africa from 1963 onward, with the most highly structured popular military mobilization the continent had ever seen.

This is not to claim that the PAIGC struggle unfolded triumphantly without internal tensions or moral compromises. The liberation war was difficult, complex, and fragmented. Nevertheless, having successfully combined armed combat with a broad and active diplomatic approach, the PAIGC managed to unilaterally proclaim Guinea-Bissau’s independence in September 1973, which was soon recognized by more than forty states.

This declaration came just months after the assassination of Cabral himself in the neighboring state of Guinea-Conakry, whose leader Ahmed Sékou Touré had long provided support to the PAIGC. The Portuguese colonial authorities clearly hoped that the PAIGC would disintegrate or accept a compromise short of full independence in the absence of Cabral. But its surviving leaders launched a major offensive soon afterward, making use of the anti-aircraft missiles that Cabral had recently obtained to contain Portugal’s previously unchallenged use of air power.

Combined with the wars in Angola and Mozambique, the conflict in Guinea-Bissau fueled internal discontent in Portugal. Many junior officers were sick of fighting what they considered an unwinnable war and began asking questions about the domestic political order. When a movement of Portuguese army captains staged a coup against the dictatorship on April 25, 1974, this developed into a fully-fledged revolution that put an end to Europe’s oldest right-wing dictatorship. The new government in Lisbon soon officially recognized the independence of all its territories in Africa.

The guerrilla struggle in the Guinean forests and villages was therefore part of the wider process of African decolonization, strengthening the anti-racist struggles in Rhodesia and South Africa. With the end of the Portuguese colonial presence in Southern Africa, the Rhodesian white-settler dictatorship of Ian Smith could only last until the end of the 1970s.

The apartheid regime in South Africa clung on for another decade, but the defeat of its army by Cuban forces in Angola in 1987–88 sounded the death knell for white supremacy in the region. After his release from prison, Nelson Mandela paid tribute to the legacy of Cabral.

Guinea-Bissau also supplied a key trigger for the most important left-wing revolutionary movement in Europe during the second half of the twentieth century. The fall of the dictatorship in Portugal then greatly accelerated the democratization of neighboring Spain after the death of Francisco Franco in 1975, as key figures in the Francoist regime feared an eruption from below if they did not begin a process of reform from above. A movement that began in Africa conjured up radical dynamics that flowed from the South to the North and back again.

Legacies

On gaining its independence, Guinea-Bissau was still a desperately poor country, which faced the same problems of poverty and economic “underdevelopment” as its West African neighbors. There were also lingering tensions between PAIGC leaders from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, where the party also took power after independence.

Those tensions gave rise to a military coup in 1980, in which the former guerrilla commander João Bernardo “Nino” Vieira ousted the country’s first president, Luís Cabral, brother of Amílcar. The PAIGC in Cape Verde broke off to form a separate party, ending hopes of unity. On the international stage, the decades following Guinea-Bissau’s independence were an increasingly bleak time for Africa, as the international financial institutions used debt as a lever to impose the so-called Washington Consensus.

We cannot know how well Amílcar Cabral would have coped with these political and economic challenges. But there is no question that the loss of such a talented leader on the eve of independence was a grievous blow to Guinea-Bissau. However, those who reduce the country’s modern history to a narrative of “failure” obscure the positive lessons we can derive from its history.

The fight for the liberation of Guinea-Bissau showed that it was possible to defeat a regime that had the backing of major imperial powers, bringing together support from different continents and subverting what was then perceived as the hegemonic logic of the international system. At a time when we are seeing a dangerous revival of old Cold War formulas, this is the kind of political imagination that the world badly needs.

Rui Lopes is a lecturer at Birkbeck and Goldsmiths, University of London, and a researcher at the Institute of Contemporary History, NOVA University of Lisbon. He was the principal investigator in the research project “Amílcar Cabral: From Political History to the Politics of Memory” (2016–19).

Víctor Barros is a researcher at the École des Hautes Études Hispaniques et Ibériques in Madrid and member of the Institute of Contemporary History, NOVA University of Lisbon. He worked as a fellow in the research project “Amílcar Cabral: From Political History to the Politics of Memory”(2016–19).

Subscribe to Jacobin today, get four beautiful editions a year, and help us build a real, socialist alternative to billionaire media.

Spread the word