Fraying Fabric

How Trade Policy and Industrial Decline Transformed America

James C. Benton

University of Illinois Press

ISBN: 978-0-252-08672-4

A native North Carolinian who is now director of the Race and Economic Empowerment Project at Georgetown University, James C. Benton witnessed the decline of the apparel and textile industry where he was born. In this book he examines the trade and protection policies of government and labor that contributed to the plight of such manufacturing across the United States. An industrial disaster befell the nation in the late twentieth century, and he attempts to explain it.

Benton opens by discussing 1974 to the present, when international agreements facilitated increased global trade and precipitated a populist revolt. What occurred was a devastating drop in United States manufacturing that in part eventually helped Donald Trump ascend to the presidency in 2016. Beginning with the 1930s, the author discovers Franklin Roosevelt and his New Deal neglecting workers’ rights through policies that lowered trade barriers. FDR was influenced by Cordell Hull, his Wilsonian free trade secretary of state. Lest organized labor object to the loss of job protection from imports, its hand was weakened by a failure to gain clout by organizing the South and a schism that cost the American Federation of Labor nearly a dozen industrial unions that created a rival federation, the CIO.

With the end of the Second World War came additional forces that weakened worker protection. The nation dominated trade, became preoccupied with global economic recovery, sponsored international cooperation, and limited unions through the Taft-Hartley Act. In addition, another disaster, Operation Dixie represented another failed attempt to organize southern workers, notably Blacks. Meanwhile, the Cold War with the Soviet Union produced a “Red Scare” at home and competition abroad for the allegiance of the world’s developing areas. Demonstrating his own belief in the international economy, in 1962 President John F. Kennedy could hail the passage of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 as a legislative achievement

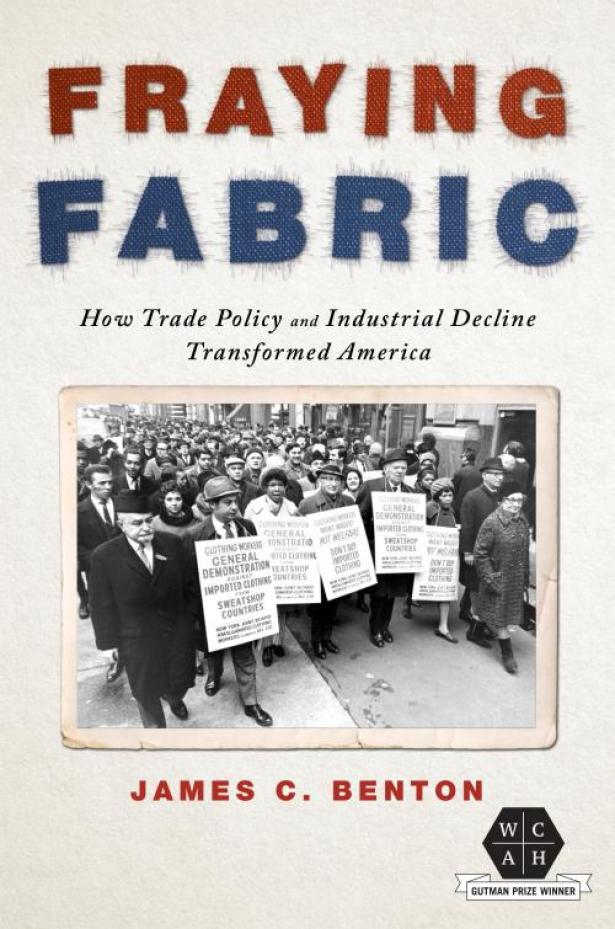

The 1960s also brought major upheavals, including assassination, urban and campus unrest, and a costly and divisive war in Vietnam. As turmoil raged, imports and prices surged, and workers sought protection. Benton observes a growing uneasiness over the growing level of imports that undermined Kennedy’s and then Lyndon Johnson’s aim “to use trade as an instrument of Cold War policy.” American garment and textile unions, such as the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA), International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA), convinced that their and the nation’s prosperity were under attack, bitterly fought imports. Nevertheless, hesitant to antagonize manufacturers who feared trade disruption and foreign retaliation, the Johnson Administration opposed quota legislation. Meanwhile, the onset of globalization became apparent.

Benton brilliantly traces the politics and mistakes that marked the 1970s. In particular, he cites the Multifiber Arrangement (MFA) of 1974, aimed at textile job protection, but loaded with “loopholes.” Designed to place a ceiling of 6 percent on incoming textiles, it suffered from omission of textile-producing sources and “evasion.” United States textile importation advanced as industry declined. “International competition, new technologies, new production methods, and marketing methods all posed steep challenges to the domestic textile industry.” Recognizing immediately that the MFA was flawed, the 117 nations that had subscribed to it substituted the World Trade Organization Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) to phase out all textile tariffs by 2005. As the duties ended, the number of apparel and textile workers in the United States declined by nearly ninety percent by 2022.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), negotiated in 1993, established a free trade zone between the United States, Canada and Mexico. It exacerbated the job losses and increased the level of protest that had been building for several years. Meanwhile, the strength of organized labor continued to plummet, having suffered a devastating blow in 1981 when President Ronald Reagan dismissed 11,000 striking air traffic controllers. The workers’ world seemed to shrink as Congress deregulated the airline and trucking industries, manufacturing plants closed, and lower trade barriers remained attractive to “the elite within the Democratic Party,” which “signaled” that it was “continuing its retreat from organized labor and its embrace of neoliberal economic policies.”

In sum Benton’s account relates a tale of despair and frustration. Without heroes or villains, and based on impressive archival research, it is a model of scholarship. Moreover, it is a work that must be read to understand the fall of the economic order by the “new era of globalization” and the political consequences that accompanied it.

Robert D. Parmet is Professor of History, York College, The City University of New York.

Spread the word