War in Ukraine: Making Sense of a Senseless Conflict

Medea Benjamin and Nicolas J. S. Davies

OR Books

ISBN 978-1-68219-371-6

Several years ago, I was sitting in a Lower Manhattan café with a friend, the journalist Arun Gupta, lamenting the state of the Left and how so many ostensible leftists had become little more than cheerleaders for reactionary politics. While downing mediocre coffee and an overpriced salad bar lunch, I listened as Arun made an incisive observation: “In the U.S., the Left has never been close to power. But even powerless, the Left has had influence through correct political analysis. The Left has shaped politics by being right.” And as I thought about it, Arun had a great point. Whether it was the labor movement, civil rights movement, the anti–Vietnam-War movement, the feminist movement, the environmental movement, or the anti-nukes movement, all were propelled into the mainstream of U.S. political life by the Left.

And so there is a tradition that we on the Left in the United States—the diseased heart of the imperial “West”—have an obligation to uphold. Our job is not to cosplay as Little Kissingers studying the global chessboard and basing our political views on the positioning of non-Western pieces. Instead, our responsibility is to discern what is real and to defend and propagate that truth in the service of internationalism and liberation from capitalist and imperialist oppression.

Our job is to help others understand violence: who is perpetrating aggression, who is victimized, and how we can stop it. Our job is to make sense of the senseless.

With that principle in mind, the new book War in Ukraine: Making Sense of a Senseless Conflict by Medea Benjamin and Nicolas J. S. Davies (of the antiwar group CODEPINK) fails on every level. It offers a myopic view of Russia’s war in Ukraine that sees the entirety of the conflict through the lens of U.S.-NATO aggression without making even a perfunctory attempt to engage with the many other critical aspects of the war: oligarch rivalries, capital accumulation, imperial revanchism, anti-communism, resource extraction, and more.

The book makes no effort to understand Ukrainian perspectives beyond casting the entire society as nameless and faceless pawns of U.S. imperialism. Similarly, the authors don’t bother to engage with any Russian perspectives—except those of Vladimir Putin—let alone provide a materialist analysis of Russian society, economy, or political institutions. It makes little mention of the events leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, save for those that involve NATO, omitting Russia’s military intervention in Kazakhstan in January 2022 to crush a worker uprising. The authors studiously avoid even a superficial analysis of the nature of the so-called People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk, how the situation came to be, or the players involved.

In fact, Benjamin and Davies ignore all the critical elements of this ghastly and criminal war apart from the wrongs of the United States and NATO. And even with respect to NATO, the authors fail to capture the complexity of its role since the end of the Soviet Union, carefully sidestepping the inconvenient examples of NATO-Russia collaboration.

It is distressing to see leaders of one of the most prominent antiwar organizations in the United States, in effect, upholding Putin’s left flank, offering up hollow condemnations of the Kremlin while using its propaganda to badly misinform the public about the nature of a war that has already shaken the global capitalist system and has the potential to end human civilization.

With that in mind, I offer this review for those interested in a serious analysis of the war and its attendant complexities, one that jettisons the fundamentally flawed framework of Benjamin and Davies and instead maintains an internationalist, anti-colonial, and authentic anti-imperialist perspective.

A Critical Look at U.S./NATO-Russia Relations

Benjamin and Davies are at their strongest when highlighting the vicious U.S.-NATO war machine, which sends arms and soldiers across the planet for military exercises, military interventions, and, of course, profits. The book provides an adequate, though uneven, introduction to the insidious role of NATO throughout the post-Soviet period, including most importantly highlighting how the U.S.-led military alliance expanded to include much of the former Soviet bloc. However, as with everything in this book, the analysis is partial and ignores many of the critical elements of the NATO-Russia relationship.

Reading Benjamin and Davies one could easily reach the conclusion that Russia and NATO have been locked in a conflict since at least 2007, if not 1991, as NATO crept its way to Russia’s border, thus presenting Russia with an “existential threat.” That aligns them with Putin, who has made the same point countless times, including in his oft-quoted 2007 speech in Munich. Conveniently, however, both Benjamin and Davies, like Putin, ignore the fact that Russia was a critical NATO partner for much of the last 20 years.

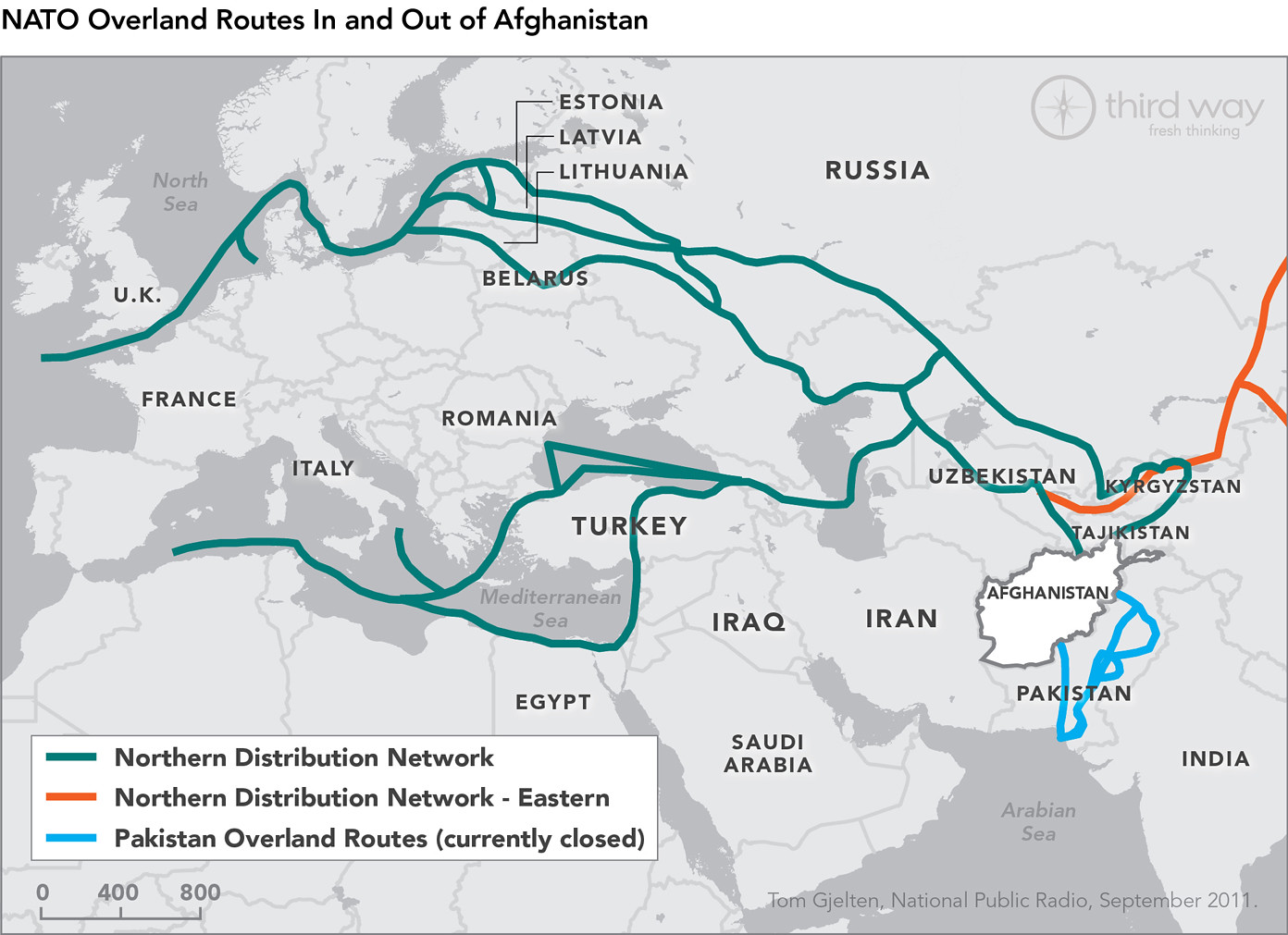

Take, for instance, the fact that Russia hosted a NATO base inside its borders for many years, and that it was a critical linchpin of NATO’s imperial infrastructure allowing the U.S. and its “NATO allies and partners” to rain death and destruction on Afghanistan for twenty-plus years. Sounds a bit odd for a country that allegedly views NATO as an existential threat. In fact, as the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute noted, “Russia was the second largest supplier of major arms to the Afghan armed forces in the period , accounting for 14 per cent of imports, by volume. All of these deliveries took place between 2002 and 2014.”

Let us recall that Russia steadfastly refused to use its UN Security Council veto to prevent the NATO-led destruction of Libya, an egregious war crime carried out by the United States, United Kingdom, France, and other powers. At the time, Russia had no significant qualms with NATO’s crime against humanity, with then-President Dmitry Medvedev—a placeholder for Putin due to constitutional term limits—saying that Russia did not veto Resolution 1973, which authorized the intervention, “for the simple reason that [Russia does] not consider the resolution in question wrong. [The resolution] reflects understanding of events in Libya too, but not completely.” So much for “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” school of realpolitik.

Map from 2012 showing NATO’s logistical supply routes, including the Northern Distribution Networks through Russia, during the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan. Graphic from Third Way Think Tank.

And, in perhaps the most distasteful of ironies, Benjamin and Davies, like some segments of the Left, allow Putin’s iteration of Bush-era neoconservative imperialism to go entirely unnoticed. How hard would it have been to point out, as I did in CounterPunch within the first two weeks of the war, that Putin was following the Bush-Cheney playbook? A little Azov Bandera Nazis in place of al-Qaeda terrorists, a few Ukrainian biolabs and a non-existent nuclear weapons program in place of “Saddam’s Weapons of Mass Destruction,” make a nice little neocon war.

Don’t take my word for it. Here’s Putin in his now infamous speech just before officially ordering the invasion:

If Ukraine acquires weapons of mass destruction, the situation in the world and in Europe will drastically change, especially for us, for Russia. We cannot but react to this real danger, all the more so since, let me repeat, Ukraine’s Western patrons may help it acquire these weapons to create yet another threat to our country.

Like a cheaply made Russian knockoff of a carcinogenic Western consumer product, Putin attempts to replicate the worst of U.S. imperialism and adapt it to his own needs. While such cynicism is to be expected from the undisputed leader of the global far right, the credulity of some on the Left, including Benjamin and Davies, toward Putin’s words is unacceptable.

About that Putin Speech…

It is interesting to note that Benjamin and Davies quote liberally from numerous Putin speeches, including the now infamous February 21, 2022, address to the Russian people in which he formally announced the invasion. And yet the authors studiously ignore all of it save for the bits about NATO. I wonder why?

Could it be because in the same speech, Putin made very clear that the war was about righting a historic wrong perpetrated by the dastardly Vladimir Lenin and those insidious Bolsheviks with their crazy ideas about the right of nations to self-determination? Could it be because Putin quite openly declares the conflict to be neocolonial in nature? Don’t believe me. Here’s Putin:

I would like to emphasize again that Ukraine is not just a neighboring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture, and spiritual space. … Since time immemorial, the people living in the southwest of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians. … So, I will start with the fact that modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia. …

This process started practically right after the 1917 revolution, and Lenin and his associates did it in a way that was extremely harsh on Russi—by separating, severing what is historically Russian land. Nobody asked the millions of people living there what they thought…When it comes to the historical destiny of Russia and its peoples, Lenin’s principles of state development were not just a mistake; they were worse than a mistake, as the saying goes. This became patently clear after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991… Soviet Ukraine is the result of the Bolsheviks’ policy and can be rightfully called “Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine.”

And today the “grateful progeny” has overturned monuments to Lenin in Ukraine. They call it decommunization. You want decommunization? Very well, this suits us just fine. But why stop halfway? We are ready to show what real decommunization would mean for Ukraine.

What Putin’s address reveals, and what Benjamin and Davies go to great lengths to ignore, is the fact that this war is, at its root, an imperial, revanchist, neocolonial war. From regarding much of Ukraine as “historically Russian land” to identifying it with Orthodox Christianity, Putin is quite openly declaring that Ukraine does not, in fact, have a right to exist. Or, to the extent that it does, it is exclusively Catholic, Western Ukraine, with the rest of the country belonging to Russia and Orthodoxy.

What do you call a war that has as its explicit goal the erasure of an entire nation? Supremacist? Genocidal? Colonial? Take your pick. Benjamin and Davies prefer to call it “self-defense.” Or to just not comment at all.

Seen from this perspective, perhaps we can finally “make sense” of Russia’s “senseless” criminal attacks on civilian infrastructure, such as Ukraine’s energy system, which Amnesty International, along with every other human rights body, describes as war crimes. Similarly, one can understand why Putin seems so cavalier about holding Europe’s biggest nuclear plant hostage, risking a catastrophic nuclear accident, since it would most acutely affect Ukrainians, who don’t really matter anyway. Likewise, we now can understand the attacks on Ukraine’s cultural institutions, including art and science museums, because a nation that has no right to exist surely has no right to its own unique culture. For Putin, Ukrainian culture is a figment of the Bolshevik imagination. (I’ve written about this erasure of Ukrainian identity elsewhere.) And, naturally, a people who do not exist have no rights.

Benjamin/Davies and Putin Agree: Ukrainians (Mostly) Don’t Exist

One of the most stunningly asinine aspects of the book is the fact that it completely ignores Ukrainian society, Ukrainian voices, and Ukrainian perspectives. There is a grand total of one Ukrainian activist cited in the book, despite the fact that every day on both traditional and social media there are countless Ukrainians from all political persuasions active on every front of this war.

The sole Ukrainian voice belongs to Yurii Sheliazhenko, a pacifist and war resister. While one can certainly respect a person’s decision to be a pacifist, it raises the question of why this was the only voice included in the book.

Benjamin and Davies could certainly have spoken with the comrades of Maksym Boutkevytch, the antifascist, anarchist, and human rights defender who co-founded the “Without Borders” project, and who since June has been a prisoner of the Russians, who dishonestly claim he’s a “Nazi.” Benjamin and Davies would have had no difficulty speaking with Taras Bilous, a Ukrainian socialist historian, editor of Commons: Journal of Social Criticism, and an activist with the left-wing Social Movement. Or Dmytro Mrachnyk, a political activist, journalist, and tattoo artist turned soldier who participated in the liberation of Kharkiv and who has seen frontline combat since the Russian invasion began. Or journalist turned soldier Yevgeny Leshan. Or, until this past Fall, Yuriy Samoilenko, the head of the antifascist football hooligan crew Hoods Hoods Klan, who became an officer in the Ukrainian Army and was killed in combat. Or members of the Solidarity Collectives, which has organized medical aid and foreign medical volunteers in places on the frontlines like Bakhmut where the reality of Russian aggression is inescapable.

So, what’s the difference between those Ukrainians listed above (and many others not mentioned) and Benjamin and Davies’ preferred Ukrainian voice? Resistance. For Benjamin and Davies, the only Ukrainian worth talking to is one who does not resist Russia’s aggression.

Russia is Putin, Putin is Russia

Another inexcusable omission in the book is the complete absence of any Russian voices and analysis of Russian society and domestic issues that may have motivated Putin’s invasion. One gets the impression from Benjamin and Davies that Russia can be reduced to Putin and his ideas about the West, the world, and Russia’s place within it. How else is one to interpret the complete lack of any Russian perspectives? The authors mention in passing the repression by the Putin regime, the suppression and outright criminalization of independent media, and other measures taken by the Kremlin, but conveniently they do not seek analysis from Russian experts.

Had they bothered to do so, they would have discovered a wide range of factors complicating the simple, myopic Russia vs. NATO narrative that is the lifeblood of the book. For instance, they could have spoken with renowned historian, sociologist, and author Boris Kagarlitsky, whom I interviewed in September 2022 about the political, economic, and social factors behind the invasion. Benjamin and Davies might have been surprised to hear Kagarlitsky explain that, while it’s self-evident that NATO expansion was imperialist, it’s also true that much of the U.S. motivation was rooted not in targeting Russia but in absorbing the post-Soviet militaries of Eastern Europe into NATO (along with their hardware) in order to use them in far-flung operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. Poland and Ukraine rank fourth and fifth in combat deaths in Iraq, for example.

As Kagarlitsky noted, “The eastward expansion of NATO was part of Western imperialist policies…but up to at least 2014 it had very little to do with Russia. It was much more about Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, and maybe China to some extent.” Kagarlitsky explains:

[NATO expansion] is one side of the coin. And the other side is Russian sub-imperialism. Russian elites accumulated enormous quantities of hard currency throughout the Putin era, and this is a very typical crisis of overaccumulation as described by Rosa Luxemburg… the Russian elite accumulated much more capital than it could use and invest inside its own country…this accumulation by both the state and private sector was enormous and led to a specific type of expansionism because Russian corporations were interested in taking over companies, and especially resources, of former Soviet Republics; Ukraine was of special interest but also Moldova, Kazakhstan, etc. And here you have a classic capitalist-imperialist conflict between competitors Western capital and corporations were moving into the same markets.

Perhaps such an analysis might have proven useful in making sense of this senseless conflict?

The “People’s Republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk: A Fairy Tale

In what is a running theme of War in Ukraine, the authors spend many pages detailing the events of 2014 and the establishment of the “People’s Republics” without ever asking any of the key questions: Who created them? How? What is daily life like there?

Indeed, an uninitiated reader would be hard-pressed to identify anything about the “People’s Republics” from the book other than some vague explanation about “anti-coup” uprisings that led to their creation. Benjamin and Davies write:

On April 7 , anti-coup protesters in Donetsk stormed a government building, declared the formation of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and announced a referendum on independence from Ukraine to take place on May 11. Luhansk followed suit on April 27, declaring the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR) and announcing a referendum for the same day as Donetsk.

And that’s it. What Benjamin and Davies omit is that nearly all significant early leaders of the “People’s Republics” were Russian-backed intelligence operatives and/or fascists with deep connections to the Russian state and fascist tendencies within it. For brevity, we’ll highlight just a few.

Igor Girkin (aka Strelkov), a Russian FSB (Federal Security Service) colonel, was an early leader of one of the primary paramilitaries involved in fomenting the conflict in Donbas. Girkin admitted as much himself when he brazenly boasted about creating the war, stating, “If our unit had not crossed the border, everything would have ended as it did in Kharkiv and in Odesa.” One would think that a book written by leaders of a prominent antiwar organization would perhaps have included such relevant information about how the war actually began.

Pavel Gubarev rose to prominence in the early days of protests in Donetsk, leading anti-Maidan rallies, the seizure of government buildings, and eventually appointing himself the first “People’s Governor.” Gubarev spent formative years as a member of Russian Nation Unity (RNE), a far-right, neo-Nazi group where he participated in training camps, and internalized a Russian imperial revanchist politics aligned with Alexander Dugin, the influential Russian fascist ideologue and political operator. Konstantin Skorkin, a Russian journalist specializing in Ukrainian politics, noted that Gubarev is understood to have been connected to, and financed by, Russian fascist oligarch Konstantin Malofeyev, who is both Dugin’s patron and was named in a federal indictment as one of the “main sources of financing for Russians promoting separatism in Crimea.”

Malofeyev, Dugin, and Gubarev are all unreconstructed imperial revanchists who see the Russian-fomented war in Donbas as an opportunity to re-establish “Novorossiya,” the Russian imperial name for the region. Dugin himself is on record saying that the goal in Donbas was not incorporation into the Russian Federation but “restoration of the old Russian Empire.”

Andrey Purgin is another of the early instigators of the conflict. He founded the “Donetsk Republic” in 2005 in direct response to the Orange Revolution of 2004, which brought the pro-western Viktor Yuschenko to power. Like Gubarev, Purgin was also connected to Dugin and Malofeyev, with activists of his organization having been trained in Dugin’s International Eurasian Movement camps. Also, like Gubarev, Purgin was sidelined by the end of 2014 in favor of more reliable United Russia party apparatchiks like Alexander Zakharchenko (succeeded by current Donetsk warlord Denis Pushilin).

But aside from the “activists” on the ground doing Russia’s bidding in fomenting the war on Donbas, there was also pro-Russian neo-Nazi infiltration of the region that helped spark what became called a “civil war.” Among those groups were the Russian Imperial Movement (RIM), described by Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation as

An extreme-right, white supremacist militant organization based in St. Petersburg, Russia promotes ethnic Russian nationalism, advocates the restoration of Russia’s tsarist regime, and seeks to fuel white supremacy extremism in the West. RIM maintains contacts with neo-Nazi and white supremacist groups across Europe and the United States…Members of RIM’s armed wing, the Imperial Legion, have fought alongside pro-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine and been involved in conflicts in Libya and Syria. In addition to its ultra-nationalist beliefs, RIM is known for its anti-Semitic and anti-Ukrainian views.

RIM was joined by Task Force Rusich, a Russian neo-Nazi mercenary outfit understood to be a cadre of the infamous Wagner Group. Task Force Rusich was especially brutal in summer 2014 when it was deployed to Donbas at the peak of the fighting that year.

I could go on and on naming all the individuals, groups, and oligarchs that are never even mentioned in a book purporting to make sense of a senseless war, but this is not a full catalog of all the players or the innumerable human rights abuses occurring in Donbas every day. Rather, it is an attempt to ask a fundamental question of both Benjamin and Davies as well as others parroting Russia’s talking points about Donbas: Why didn’t they bother to study the war before forming their political position on the issue?

Similarly, why didn’t Benjamin and Davies examine the financial flows to and from Donbas? Had they done so they might have discovered a company called VneshTorgServis, which is headed by a Putin ally and former governor of Irkutsk region, Vladimir Pashkov. The company was established to take control of seized Ukrainian factories and funnel the revenues, resources, and capital goods into the pockets of Kremlin-connected insiders. Some of the factories seized by Russia’s proxies and turned into money-makers for Russia’s oligarchs and elite include Donetsksteel Iron and Steel Works, Yenakiieve and Makiivka Iron and Steel Works, Yenakiieve Coke and Chemicals Plant, Yasinovka Coke Plant, Makiivkoks, and Khartsyzsk Tube Works.

Why Understanding the War Matters So Much

Were this a simple disagreement among U.S. leftists, I would never have bothered to critique this book. But how we understand the nature of this war directly informs how we develop a sound leftist position on it and how we rebuild our international movement.

Reading Benjamin and Davies leaves one with the simple, straightforward analysis, dominant in some corners of the Left, that this is an easily understood proxy war between NATO and Russia. Seen through this distorted lens, one could understand why some on the Left call for an end to the war via “peace negotiations” (and dismembering of Ukraine) and oppose sending vital weapons to those fighting the Russian invaders.

However, a serious examination of the war and its many dimensions leads to the very different conclusion that Ukraine has been invaded by an aggressive sub-imperial state, which also happens to be the traditional colonial power in the region, and that resistance to such aggression is not only justified, but a prerequisite for the survival of the people of Ukraine and the defense of their right to self-determination. In fact, such an analysis leads to the logical conclusion that opposing Ukraine’s right to defend itself and eject its invaders is an abandonment of every principle of internationalism, solidarity, and anti-colonial and anti-imperialist politics.

Some Concluding Thoughts

While I don’t know Davies, it is truly a shame to see Benjamin, whose work I’ve often found valuable and whom I’ve hosted on my podcast, degrade herself with such an embarrassing distortion of an extremely complex and exceedingly dangerous war.

Benjamin and Davies, like Noam Chomsky and Katrina vanden Heuvel (who contributed the preface to this book), are correct that the threat of nuclear war still looms over everything happening in Ukraine, and everyone globally should be concerned about that. They are also correct that U.S.-NATO imperialism is critical to understanding the invasion. Unfortunately, the book they’ve produced misinforms more than it informs and distorts more than it clarifies.

Benjamin and Davies have done a tremendous disservice to the people of Ukraine resisting an invasion, the people of Russia living under (especially those resisting) a criminal regime, and the international Left as a whole. And in so doing, they provide left cover for Putin’s war machine. Echoing Gupta, even if the Left in the United States lacks effective power at the moment, we must at the very least provide a serious analysis, based on historical truths as well as current political realities. Anything less fails all those suffering under the guns of imperial aggressors—in this case, the forces led by Vladimir Putin.

Spread the word