With the exception of the Second World War, every military conflict in which the United States has taken part has generated an anti-war movement. During the American Revolution, numerous Loyalists preferred British rule to a war for independence. New Englanders opposed the War of 1812; most Whigs denounced the Mexican-American War launched by the Democratic president James K. Polk; and both the Union and the Confederacy were internally divided during the Civil War. More recently, the wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan split the country. At the same time, wars often create an atmosphere of hyper-patriotism, leading to the equation of dissent with treason and to the severe treatment of critics. During the struggle for independence, many Loyalists were driven into exile. Both sides in the Civil War arrested critics and suppressed anti-war newspapers. But by far the most extreme wartime violations of civil liberties (with the major exception of Japanese American internment during the Second World War) took place during World War I. This is the subject of Adam Hochschild’s latest book, American Midnight.

Adam Hochschild is one of the few historians whose works regularly appear on best-seller lists, a tribute to his lucid writing style, careful research, and unusual choice of subject matter. Most historians who reach an audience outside the academy focus on inspirational figures like the founding fathers or formidable achievements such as the building of the transcontinental railroad. Hochschild, on the other hand, writes about villains and rebels. His best-known book, King Leopold’s Ghost, is an account of the Belgian monarch’s violent exploitation of the Congo, one of the worst crimes against humanity in a continent that has suffered far too many of them. When Hochschild writes about more admirable figures, his heroes are activists and reformers: British antislavery campaigners in Bury the Chains, the birth control advocate and socialist Rose Pastor Stokes in Rebel Cinderella, the Americans who fought in the Spanish Civil War in Spain in Our Hearts.

American Midnight does not lack for heroic figures. But as Hochschild notes at the outset, the book presents a tale of “mass imprisonments, torture, vigilante violence, censorship, killings of Black Americans.” It will certainly not enhance the reputation of President Woodrow Wilson or that of early 20th-century liberalism more broadly, nor will it reinforce the widely held idea that Americans possess an exceptional devotion to liberty.

Hochschild relates how, when the United States joined the conflict against Germany and its allies in 1917, “war fever swept the land.” Some examples of the widespread paranoia seem absurd: Hamburgers became “liberty sandwiches,” frankfurters “hot dogs.” (The latter name stuck, unlike the rechristening of french fries as “freedom fries” in 2003, after France refused to support the Iraq War.) The German Hospital and Dispensary in New York City changed its name to Lenox Hill Hospital (even though no hill is to be found nearby). In New Haven, Conn., volunteers manned an anti-aircraft gun around the clock, oblivious to the fact that Germany had no aircraft capable of reaching the United States. Neighbors accused Karl Muck, the German-born conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, of radioing military information to submarines from his vacation home on the coast of Maine. Anecdotes like these have long enlivened history classrooms. But Hochschild also details the brutal treatment of conscientious objectors subjected to various forms of torture in military prison camps, including the infamous “water cure” the Army had employed in the Philippines, nowadays known as waterboarding.

In 1917 and 1918, Wilson and Congress codified this patriotic fervor in the Espionage and Sedition Acts. These laws had nothing to do with espionage as the term is commonly understood (and Hochschild points out that hardly any German spies were actually apprehended). The former criminalized almost any utterance that might interfere with the war effort; the latter outlawed saying or printing anything that cast “disrepute” on the country’s “form of government.” States supplemented these measures with their own laws and decrees, including banning speaking on the telephone in German or advocating “a change in industrial ownership.” It is difficult to say how many people were arrested under these statutes, but the number certainly reached into the thousands.

Meanwhile, private organizations such as the Knights of Liberty and the American Protection League took the law into their own hands. The APL investigated the “disloyal” by, among other methods, purloining documents, and it swept up thousands of Americans in “slacker raids,” in which men were accosted on the streets, in hotels, and in railway stations and were required to produce draft cards. If a person did not have one, he would be dragged off to prison. Throughout the country, individuals who refused to buy war bonds were tarred and feathered and paraded through their communities. German Americans everywhere came under suspicion for disloyalty, as did members of other immigrant groups. In the years before the war, Southern and Eastern Europeans had immigrated to the United States in unprecedented numbers, sometimes bringing political radicalism with them, and they too found themselves in the crosshairs of nativism.

The atmosphere of intolerance opened the door to settling scores that predated the war. Long anxious to rid the nation of the Industrial Workers of the World, business leaders and local and national officials seized on the organization’s outspoken opposition to the war to crush it. All sorts of atrocities were committed against IWW members, from Frank Little, an organizer who was lynched in Montana, to the more than 1,000 striking copper miners in Bisbee, Ariz., who were rounded up by police and a small private army hired by the Phelps Dodge company, then driven into the desert and left to fend for themselves. Local police routinely raided the IWW’s offices without a warrant. In 1918, over 100 “Wobblies” were indicted for conspiracy to violate the Espionage and Sedition Acts, resulting in the largest civilian criminal trial in American history. Every defendant was found guilty and received a jail sentence.

Hochschild brings this history to life by introducing the reader to a diverse cast of characters, some well-known, many unfamiliar even to scholars. His protagonists include Ralph Van Deman, who oversaw the surveillance of Americans deemed unpatriotic. Having honed his skills in the Philippines by keeping track of opponents of American annexation, Van Deman became head of the newly created Army Intelligence branch—the first time, according to Hochschild, that the US Army spied on American civilians. One of Van Deman’s men was among the first to tap Americans’ telephones. The surveillance reports in government archives also allowed Hochschild to follow the exploits of Louis Walsh, a militant labor activist in Pittsburgh who was actually Leo Wendell, a paid government agent who sent a “blizzard” of paperwork to the Bureau of Investigation, the FBI’s forerunner. Wendell boasted of joining “prominent Reds” in stirring up violence, providing a justification for further repression.

The Espionage Act empowered the Post Office to exclude from the mail publications that undermined the war effort. Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson interpreted this as an authorization to go after any published expression of dissent. In the first year of American participation in the war, Burleson banned 44 periodicals. He also suppressed individual issues of other publications, including the one you are reading now. Issues of The Gaelic American, a supporter of Irish independence, were barred for fear of offending our British ally. Burleson particularly targeted the Socialist Party press, which consisted of numerous small local newspapers—a powerful blow against the party’s efforts to communicate with its membership. His first target, though, was a small Texas newspaper, The Rebel, whose offense had less to do with the war than with having published an exposé of how Burleson had replaced Mexican and white tenant farmers with convict laborers on a cotton plantation his wife had inherited. And his crusade against unorthodox opinion continued after the armistice: Even as the Paris Peace Conference deliberated in 1919, the New York World commented, Burleson acted as if “the war is either just beginning or is still going on.”

To ensure that Americans received the right kind of news, not the “false statements” criminalized by the Espionage Act, the federal government launched a massive wartime propaganda campaign, spearheaded by the newly created Committee on Public Information. Headed by the journalist George Creel, the CPI flooded the country with publications, films, and posters. It mobilized journalists, academics, and artists to produce pro-war works, as well as some 75,000 “Four Minute Men” trained to deliver brief speeches at venues including churches, movie theaters, and county fairs. In previous wars, such propaganda had been disseminated by nongovernmental organizations. But Wilson decided that patriotism was too important to be left to the private sector. Much of Creel’s output whipped up hatred of the Germans as barbaric “Huns.” But he also put forth a vision of the country’s future strongly influenced by the era’s Progressive movement, a postwar world in which democracy would be extended into the workplace and the vast gap between rich and poor ameliorated. This wartime rhetoric was one contributor to an upsurge of radicalism after the conflict ended, when it became apparent that no such changes were in the offing. Creel’s success at shaping wartime public opinion, Hochschild remarks, launched the symbiotic relationship between advertising and politics so visible today. It alarmed observers like the political commentator Walter Lippmann, who in a series of writings in the 1920s lamented that while democracy required an independent-minded citizenry, the war experience demonstrated that public opinion could be shaped and manipulated by the authorities.

Then there was Wilson’s attorney general, A. Mitchell Palmer. Obsessed with deporting radical immigrants, the “fighting Quaker,” as the press called him, launched what came to be known as the Palmer Raids, which lasted from November 1919 into the following year. By this point, the First World War was over, but not the Wilson administration’s war on the American left. Thousands of people—critics of the war and suspected socialists and anarchists—were arrested, mostly without a warrant. Many who had recently immigrated and not become citizens were deported. The Palmer Raids dealt a serious blow to the left, and they were followed by one of the most conservative decades in US history.

American Midnight does introduce the reader to more praiseworthy figures. Hochschild devotes considerable attention to the great anarchist and feminist orator Emma Goldman, who spent much of the war in prison for conspiracy to interfere with the draft and was deported a year after the arrival of peace as an undesirable alien. In contrast to Burleson, Palmer, and the enigmatic Wilson, whom Hochschild describes as simultaneously an “inspirational idealist” and a “nativist autocrat,” a few government officials remained committed to constitutional principles. If the book has a hero, it is Louis F. Post, the assistant secretary of labor, who ran the Labor Department in the spring of 1920 when his boss was away because of family illness. Post’s career embodied much of the 19th-century radical tradition: His forebears were abolitionists, and he himself participated in Reconstruction in the South. Post was an ardent follower of Henry George, the popular late 19th-century economist who proposed a “single tax” on land to combat economic inequality. For a time, Post edited a magazine that opposed America’s war in the Philippines, denounced the power of big business, and called for unrestricted immigration. He directed the Labor Department for only six months, but in that time he invalidated thousands of deportation orders that lacked the proper paperwork and released numerous immigrants being held, ironically, at Ellis Island awaiting expulsion from the United States. He also refused to be intimidated when a congressional committee held hearings about his actions.

One individual who doesn’t quite get the attention he deserves is Eugene V. Debs, the most prominent leader of the Socialist Party, which on the eve of the war was a major presence in parts of the United States, with 150,000 dues-paying members and a thriving local press. The party controlled the local government in many working-class communities, sent elected members to Congress, and won almost 1 million votes for Debs in the presidential election of 1912. Compared with the colorful IWW, with its Little Red Songbook and its rallying cry of “One Big Union,” the Socialists seem boringly respectable, which perhaps accounts for their relative neglect here. But they arguably had a greater impact on American life. The Socialist Party was the largest organization to oppose America’s entry into the war.

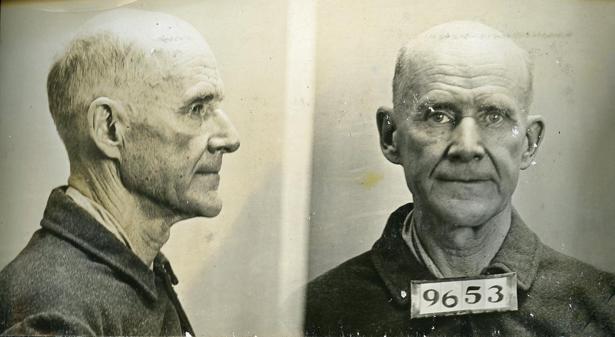

Debs was arrested in 1918 after delivering a speech in Canton, Ohio, critical of the draft. He received a sentence of 10 years in prison for violating the Espionage Act. Before his sentencing, he delivered a brief speech to the jury that remains a classic vindication of freedom of expression. “I look upon the Espionage Law as a despotic enactment in flagrant conflict with democratic principles and with the spirit of free institutions,” Debs declared. He traced the right to criticize the government from Thomas Paine to the abolitionists and women’s suffrage leaders. While Wilson and his administration proclaimed themselves the creators of a new, liberal world order, Debs asked, “Isn’t it strange that we Socialists stand almost alone today in upholding and defending the Constitution of the United States?” After the war ended, Wilson rebuffed appeals for Debs’s release. “I will never consent to the pardon of this man,” he declared. It was left to his successor, Warren G. Harding, a conservative Republican, to free Debs from prison in 1921.

Hochschild presents a vivid account of this turbulent time. But he does not really explain one of its many disturbing features: why so many Progressive-era intellectuals failed to raise their voices against the suppression of free speech. Many, in fact, enlisted in the CPI’s propaganda campaign. Although the Progressive movement, which envisioned government as an embodiment of democratic purpose, is sometimes viewed as a precursor of the New Deal and the Great Society, it differed from them in a crucial respect: Civil liberties were not among the Progressives’ major concerns. Many saw the lone person standing up to authority as an example of excessive individualism, which they identified as a cause of many of the nation’s problems. They believed that the expansion of federal power required by the war would enable their movement to fulfill many of its goals for social reconstruction, from the public regulation of business to the creation of social welfare programs, and they also hoped that the mobilization of America for war would help integrate recent immigrants into a more harmonious and more equal society.

Hochschild says nothing about one of the most memorable exchanges of these years, the debate over American participation in the war between the prominent intellectual John Dewey and the brilliant young writer Randolph Bourne. Hailing the “social possibilities” created by the conflict, Dewey urged Progressives to support American involvement. In response, Bourne ridiculed the idea that forward-looking thinkers could guide the conflict according to their own “liberal purposes.” It was far more likely, he wrote, that the war would empower the “least democratic forces in American life.” War, Bourne famously declared, “is the health of the state,” and as such posed a threat to individual liberty.

Despite the clear words of the First Amendment, the Supreme Court offered no assistance to those seeking to defend civil liberties. Early in 1919, the justices unanimously sustained the conviction of the Socialist Party’s Charles T. Schenck for violating the Espionage Act by distributing leaflets opposing the draft. A week later, it upheld Debs’s conviction. The same result followed in 1919 in the case of Jacob Abrams and four others jailed for distributing publications opposing US intervention in the Russian Civil War. This time, however, Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis dissented. The next year, 1920, saw the formation of the American Civil Liberties Union, founded by an impressive group of believers in free speech, including Jane Addams, Roger N. Baldwin, Helen Keller, and Oswald Garrison Villard, the editor of The Nation. The ACLU would wage a long battle to invigorate the First Amendment. Its efforts were initially stymied, its own pamphlets defending civil liberties barred from the mail. But the excesses of wartime repression were finally beginning to generate opposition.

How can we explain the “explosion of martial ferocity” in a country where respect for the free individual is supposedly the culture’s bedrock? Hochschild doesn’t offer a single explanation, but he directs the reader’s attention to a number of factors—historical, material, political, and psychological—that “fed the violence.” They include nativism, which made it easy to identify radical ideas with immigrants; the “brutal habits” (which is to say, a penchant for torture) picked up by the military in the Philippine-American War; and the long-standing hostility of business leaders to trade unions and socialists. He notes that Palmer sought the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination in 1920, hoping to ride the hysteria he had helped create all the way to the White House. Hochschild also suggests that American men felt uneasy at a time when “the balance of power between the sexes” was changing, with women rapidly moving into the workplace and the campaign for women’s suffrage reaching its culmination. War offered a way to reinvigorate an endangered masculinity. As Lippmann observed, World War I created a situation in which all sorts of preexisting prejudices and fears could be acted out, a perfect storm in which “hatreds and violence…turned against all kinds of imaginary enemies.”

One additional element should be noted: As Black Americans streamed out of the South to take up jobs suddenly available in Northern industry because the war cut off European immigration, “race riots” broke out in East St. Louis, Chicago, Tulsa, and other cities. Protests by Blacks who came to realize that Wilson’s rhetoric about democracy did not apply to the American South were met with an upsurge in lynchings. Some of the victims were soldiers still in uniform. W.E.B. Du Bois had urged Black people to enlist in the armed forces to stake a claim to equal citizenship. Instead, as he put it, “the forces of hell” had been unleashed “in our own land.”

Wilson’s deep-seated racism has been the subject of much discussion in the past few years. Princeton University recently removed his name from its School of International and Public Affairs. (This step was taken almost entirely because of his racial views; there was little discussion of the wartime suppression of civil liberties.) The first Southern-born president elected since the Civil War, Wilson grew up in Columbia, S.C., during Reconstruction, a time of major gains for African Americans but also a campaign of violence by the Ku Klux Klan and kindred organizations. Wilson shared the prevailing disdain among white Southerners for the enfranchisement of Black voters during Reconstruction and embraced the system known as Jim Crow that followed, which locked Blacks into second-class citizenship. One of his initiatives as president was to segregate the civil service in Washington, D.C.

Copyright c 2023 The Nation. Reprinted with permission. May not be reprinted without permission. Distributed by PARS International Corp.

Eric Foner, a member of The Nation’s editorial board and the DeWitt Clinton Professor Emeritus of History at Columbia University, is the author, most recently, of The Second Founding: How the Civil War and Reconstruction Remade the Constitution.

The Nation Founded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.

Please support progressive journalism. Get a digital subscription to The Nation for just $24.95!

Spread the word