A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. – Second Amendment, U.S. Constitution

When, on June 8, 1789, James Madison took to the floor of the House of Representatives to propose a collection of constitutional amendments – some of which, he said, “may be called a bill of rights” – he faced a steep climb. Few in the First Congress wanted to adopt a bill of rights, at least then. “The Constitution may be compared to a ship that has never put to sea,” said one congressman. It needed to be tested before decisions could be made about amending it.

Madison himself had opposed a bill of rights during the Constitutional Convention and the ratification process. He believed that rights were better secured through governmental structure than through what he called “parchment barriers.” He also worried that any list of rights would generate arguments that anything omitted was not a right.

What changed Madison’s mind? And why did he include the Second Amendment?

The answers to those questions begin one year earlier. By its own terms, the Constitution had to be ratified by at least nine states at special ratifying conventions. When Virginia’s ratifying convention convened in Richmond in June of 1788, eight states had ratified, but if Virginia failed to ratify, it was by no means clear that there would be ninth state.

Federalists and antifederalists battled fiercely for a nearly a full month in Richmond. Madison led the federalists, who wanted a strong national government and favored ratification. The antifederalists, who feared a strong national government and opposed ratification, were led by Patrick Henry and George Mason. Henry, Virginia’s first governor and the most politically powerful person in the state, was considered America’s greatest orator. Mason was one of three delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia who had refused to sign the Constitution.

One of many arguments that Henry and Mason deployed in Richmond concerned the militia. Until then, states controlled their militia. But the Constitution gave Congress the power to organize, arm, and discipline the militia. The states were only given the authority to appoint officers and train the militia in accordance with the discipline prescribed by Congress. Time and again, Henry and Mason argued that Congress might “neglect or refuse” to arm the militia, on which the South relied for slave control. “The militia may be here destroyed by that method which has been practiced in other parts of the world before; that is, by rendering them useless – by disarming them,” Mason declared. Henry argued that authority to arm the militia implied the authority to disarm it, and he raised the specter of Congress – controlled by a faster-growing, increasingly abolitionist North – doing exactly that.

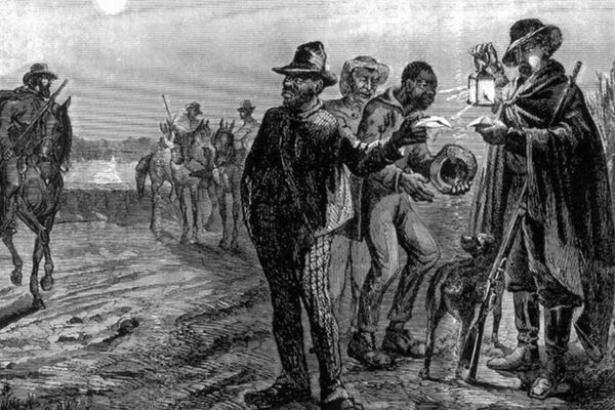

Southerners lived in terror of slave revolts. In 1739, an insurrection in Stono, South Carolina by 60-100 slaves, armed with stolen muskets, left more than 60 White slaveowners, family members, and militiamen dead. No one knows how large the rebellion might have grown, or what the death toll would have been, if militia had not snuffed out the revolt before the end of its first day. In Eastern Virginia, where many of the Founders lived and the Richmond debate was taking place, enslaved Blacks outnumbered Whites. At night, militia groups patrolled designated areas – called “beats” – to ensure slaves were where they were supposed to be (this is where the terms patrols and policeman’s beat originated).

But while militia were essential for slave control, the Revolutionary War had demonstrated they were useless as a military force. Lexington and Concord were the only true militia victories. In the face of the enemy, militia repeatedly threw down their muskets and fled. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee, a hero of the Revolutionary War, told the Richmond convention that he “could enumerate many instances” of militia unreliability but would describe just one: how Continental soldiers behaved with “gallant intrepidity” and militiamen fled at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Other Virginians had previously reported much the same. George Washington repeatedly expressed disgust with militia. After Virginia militia bolted without firing a single shot at the Battle of Camden, their own commander told Governor Thomas Jefferson, “ilitia I plainly see won’t do.”

When Madison argued that Virginia could arm its own militia if Congress failed to do so, Henry ridiculed him. The Constitution allocated some powers to Congress and others to the states. “To admit this mutual concurrence of powers will carry you into endless absurdity – Congress has nothing exclusive on the one hand, nor the states on the other,” Henry said. He was, of course, right.

The federalists prevailed at Richmond, but just barely. The key vote was 88-80.

Henry then worked to extinguish Madison’s political career. He had the state legislature send two other men to the U.S. Senate, gerrymandered Madison’s congressional district by packing it with antifederalist counties, and recruited rising star James Monroe to run against Madison for the House. Monroe intended to campaign on his support for, and Madison’s opposition to, a bill of rights. And so, Madison flipped – promising, if elected, to write a bill of rights.

Madison won the election, yet he continued in jeopardy as long as Henry remained powerful. “Poor Madison got so cursedly frightened in Virginia that I believe he has dreamed of amendments ever since,” said one of Madison’s congressional colleagues. Another said Madison was “haunted by the ghost of Patrick Henry.” It makes perfect sense that, in writing a bill of rights, Madison would try to cure the problem Henry and Mason raised in Richmond. Madison could not expressly give states the right to arm the militia because he vowed his amendments would not contradict anything in the Constitution. In fact, states rarely armed their militia; they simply passed laws requiring militiamen to furnish their own arms. By using that model, Madison was able to write an amendment that assured his constituents – and the South generally – that they would have an armed militia for internal security.

Carl T. Bogus is an author and Distinguished Research Professor of Law at Roger Williams University School of Law in Rhode Island. He is the author of three books: Buckley: William F. Buckley Jr. and the Rise of American Conservatism (Bloomsbury Press 2011), Why Lawsuits Are Good for America: Big Business, Disciplined Democracy and the Common Law (NYU Press 2001) and Madison's Militia: The Hidden History of the Second Amendment (Oxford University Press 2023). Bogus has received the Ross Essay Award from the American Bar Association and the Public Service Achievement Award from Common Cause of Rhode Island.

History News Network depends on the generosity of its community of readers. If you enjoy HNN and value our work to put the news in historical perspective, please consider making a donation today!

Spread the word