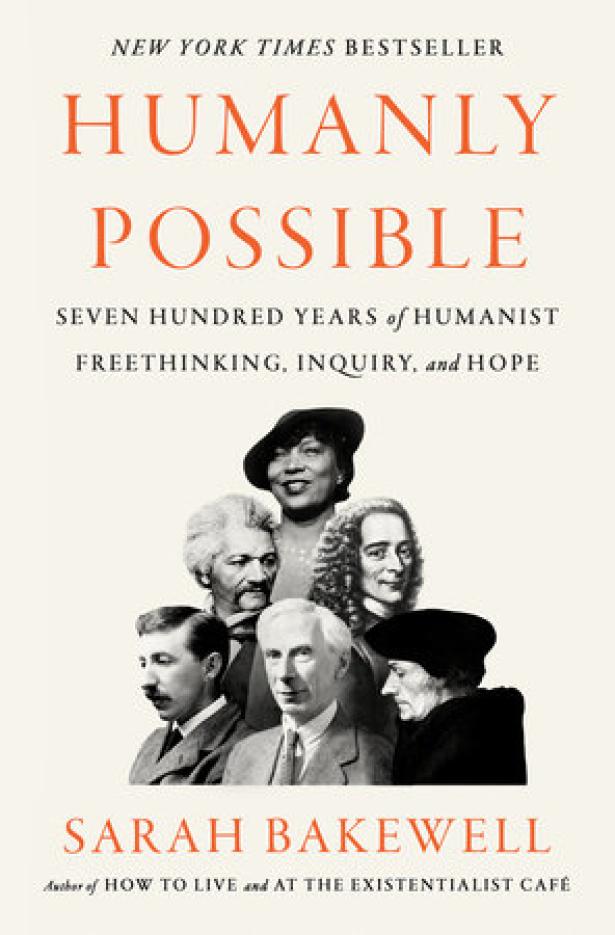

Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope

Sarah Bakewell

Penguin Press

ISBN: 9780735223370

“I am human, and consider nothing human alien to me”: The famous line from the Roman playwright Terence, written more than two millenniums ago, is easy to assert but hard to live by, at least with any consistency. The attitude it suggests is adamantly open-minded and resolutely pluralist: Even the most annoying, the most confounding, the most atrocious example of anyone’s behavior is necessarily part of the human experience. There are points of connection between all of us weirdos, no matter how different we are. Michel de Montaigne liked the line so much that he had the Latin original — Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto — inscribed on a ceiling joist in his library.

But as Sarah Bakewell notes in her lively new book, “Humanly Possible,” Terence wrote the line as a joke. It’s said by a busybody character after being asked why he cannot seem to keep his nose out of everybody else’s beeswax. This sly double meaning is what makes the line so fitting for the capacious tradition known as humanism that Bakewell writes about. On the one hand, the quote offers a high-minded philosophical sentiment; on the other, it’s a playful gag. Humanism, too, has always had to negotiate between noble ideals of humanity and the peculiarities of actual humans. Paradox and ambiguity aren’t to be rejected but embraced. “Dispute and contradiction, not veneration and obedience, are the essence of intellectual life,” Bakewell writes.

The value of debate and skepticism sounds fairly unobjectionable now, but as Bakewell shows, this turned out to be a radical way of apprehending the world. She begins her story in earnest in the 1300s, during the early Renaissance, and ends with the present day. “Understanding human life non-supernaturally,” as she puts it, was — even for those humanists who didn’t reject religion outright — a startling rebuke to religious doctrine. Immediate kindnesses should be valued for being immediate kindnesses, not because they brought any kind of glory in an afterlife. A focus on the here and now made for an intrinsic irreverence. The poet Petrarch wrote letters to classical authors he admired and signed off with the words “From the land of the living.” His friend Boccaccio wrote about pantless priests and bawdy nuns.

Bakewell is the author of several books, including the marvelous “How to Live” (a biography of Montaigne) and the terrific “At the Existentialist Café.” Her new book is filled with her characteristic wit and clarity; she manages to wrangle seven centuries of humanist thought into a brisk narrative, resisting the traps of windy abstraction and glib oversimplification. But covering such enormous terrain means that “Humanly Possible” doesn’t quite have the bracing focus of her earlier work, even if there are several points of overlap. “Humanism is personal, and it is a semantic cloud of meanings and implications, none attachable to any particular theorist or practitioner,” she writes. Saying that humanists “all look to the human dimension of life” narrows it down somewhat, but only up to a point. To put it another way, how do you keep your story contained when nothing human could be alien to humanism?

But the humanist tendency toward moderation has often turned out to be helpless against the anti-humanist forces of extermination. In 1935, as Nazism was ascendant, Thomas Mann noticed that in “humanism there is an element of weakness,” which he predicted “may be its ruin.” Bakewell puts the charge against humanists another way: “They always try to see the other side of any question. When dealing with murderous fanaticism, that is not necessarily helpful.” They risked both-sidesing themselves into oblivion.

Bakewell concedes that the anti-humanist critique is important, so that humanists don’t become too smug or complacent. But she identifies in anti-humanism a kind of complacency, too — a nihilism, or fatalism, which assumes that the impossibility of perfection should drive us into a quest for domination or else the depths of despair. Humanists put a lot of stock in reason, although a good humanist will also admit that when it comes to reason, nobody has a monopoly on it. This is why rhetoric isn’t a matter of wily persuasion but “a moral activity,” she says. Writing about Frederick Douglass, whose skills as a writer and orator were a matter of life and death, Bakewell extols the power of language to connect us.

To that end, Bakewell practices what she preaches — or, since preaching would be anathema to a humanist, she does what she suggests. She puts her entire self into this book, linking philosophical reflections with vibrant anecdotes. She delights in the paradoxical and the particular, reminding us that every human being contains multitudes.

This can lead her to some wonderful asides. In his book “On Good Manners for Boys,” Erasmus included some tips on what to do if one needs to pass gas in polite company, advising the flatulent boy to keep his brow unfurrowed, “not irresolute like a hedgehog’s; not menacing like a bull’s.” When Bertrand Russell was in a seaplane accident in Norway and a journalist called him afterward to ask whether his brush with death had led him to think about such high-flown concepts as mysticism and logic, he said no, it had not. “I thought the water was cold.”

Spread the word