How could it be that the largest-ever recorded drop in childhood poverty had next to no political resonance?

One of us became intrigued by this question when he walked into a graduate class one evening in 2021 and received unexpected and bracing lessons about the limits of progressive economic policy from his students.

Deepak had worked on various efforts to secure expanded income support for a long time—and was part of a successful push over two decades earlier to increase the child tax credit, a rare win under the George W. Bush presidency. His students were mostly working-class adults of color with full-time jobs, and many were parents. Knowing that the newly expanded child tax credit would be particularly helpful to his students, he entered the class elated. The money had started to hit people’s bank accounts, and he was eager to hear about how the extra income would improve their lives. He asked how many of them had received the check. More than half raised their hands. Then he asked those students whether they were happy about it. Not one hand went up.

Baffled, Deepak asked why. One student gave voice to the vibe, asking, “What’s the catch?” As the class unfolded, students shared that they had not experienced government as a benevolent force. They assumed that the money would be recaptured later with penalties. It was, surely, a trap. And of course, in light of centuries of exploitation and deceit—in criminal justice, housing, and safety net systems—working-class people of color are not wrong to mistrust government bureaucracies and institutions. The real passion in the class that night, and many nights, was about crime and what it was like to take the subway at night after class. These students were overwhelmingly progressive on economic and social issues, but many of their everyday concerns were spoken to by the right, not the left.

The American Rescue Plan’s temporary expansion of the child tax credit lifted more than 2 million children out of poverty, resulting in an astounding 46 percent reduction in child poverty. Yet the policy’s lapse sparked almost no political response, either from its champions or its beneficiaries. Democrats hardly campaigned on the remarkable achievement they had just delivered, and the millions of parents impacted by the policy did not seem to feel that it made much difference in their day-to-day lives. Even those who experienced the greatest benefit from the expanded child tax credit appeared unmoved by the policy. In fact, during the same time span in which monthly deposits landed in beneficiaries’ bank accounts, the percentage of Black voters—a group that especially benefited from the policy—who said their lives had improved under the Biden Administration actually declined.

Explaining the Disconnect

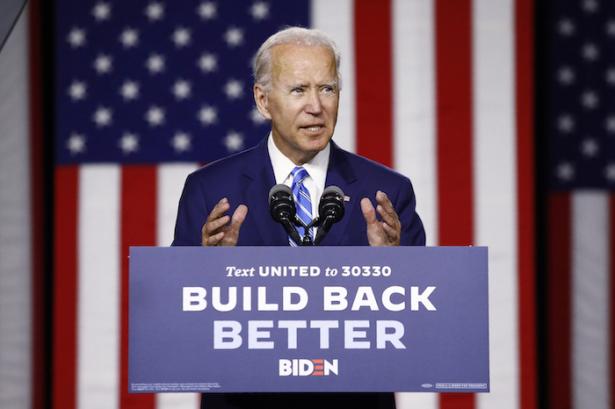

More broadly, the suite of progressive economic policies Biden enacted hasn’t made a dent in his approval ratings. Sixty-two percent of Americans said in a poll from early 2023 that Biden has accomplished “not very much” or “little or nothing” during his presidency. The ambitious drive to “Build Back Better” after the COVID-19 economic shock wasn’t as far-reaching as progressives (or Biden) had hoped, but taken together, the American Rescue Plan, the CHIPS and Science Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act constitute a sweeping effort to remake the U.S. economy. Many progressive groups are turning their attention to implementation of these major pieces of legislation, which is worthy work, whether it has political consequences or not. But it’s a remarkable feat to spend trillions in an attempt to usher in an economic transformation and to get such an underwhelming response.

It has long been an article of faith among liberals and leftists that if you “deliver” for people—specifically, if you deliver economic improvements in people’s lives through policy—these changes will solidify or shift people’s political allegiances. Ironically, this transactional vision of politics echoes a naive assumption more commonly associated with economists, particularly neoliberals: that humans are rational actors motivated above all by immediate material interests. After the 2022 midterm election, Elizabeth Warren wrote an op-ed in The New York Times that exemplifies this way of thinking. She contended that “Voters rewarded Democrats for protecting the lives and livelihoods of struggling families,” citing things like allowing Medicare to lower drug prices, capping insulin costs, and increasing corporate taxes. A more accurate look at the 2022 election results, however, shows that they were highly geographically uneven, and that the unusually good results for Democrats came in places where reproductive rights were under threat and where people felt their votes mattered as a stand against MAGA extremism. Biden’s economic record played little role in persuading voters—and in much of the country, authoritarian candidates prevailed.

We use the term “deliverism” to describe the presumption of a linear and direct relationship between economic policy and people’s political allegiances. Originally coined by Matt Stoller and expanded on by David Dayen, the word broadly describes an approach to governing that focuses on enacting and implementing policies to improve people’s lives. Stoller and Dayen situate the concept as an alternative to popularism, arguing that it’s not enough for progressives to simply talk about popular policies—they must also actually deliver on the policies they claim to support. In exchange for enacting these policies, deliverism holds, voters will reward progressives at the ballot box. Centrists, liberals, and progressives in politics and in outside social movements disagree about many things, but deliverism is a worldview that unites most of them.

However, progressive economic policies do not necessarily lead to the political outcomes that deliverism predicts they should, and deliverism is proving ineffectual as a response to authoritarianism. People are fully capable of supporting or ignoring progressive economic policies while voting for authoritarians. In 2020 in Florida, for example, more than 60 percent of voters supported a ballot initiative to raise the state minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2026—the same state where a majority also voted for Trump. Last year Nebraska passed a similar measure despite overwhelming support for Trump in both the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections. And we’ve seen this movie before: Political scientist Dan Hopkins shows that President Obama’s signature achievement, the Affordable Care Act, did virtually nothing to shift political allegiances and had a minimal impact on the political behavior of even its direct beneficiaries.

Although we have long been sympathetic to deliverism, we now believe that it is mostly wrong. Delivering for people on economic issues is an important goal in itself, but it is not an antivenom for the snakebite of authoritarianism.

There are many reasons why economic policy and political behavior might be disconnected. People might not know about a policy, why it happened, or who brought it about. (There is a long history of politicians blaming faulty “messaging” for the lack of popularity of their policies. And to be sure, getting better at communicating with voters is important.) A policy may not be large enough or not get implemented soon or well enough for people to see a direct impact in their lives. (Sometimes policies are designed to make their impact on beneficiaries invisible, as was the case with Obama’s middle-class tax cuts.) In some cases, a policy simply may not feel particularly salient to some people. The media frequently fail to explain the relationship between policies and people’s everyday lives. Often the right has already done such a good job of inoculating people against the idea of government as a benevolent force that many are unable to see it working to make their lives better. And both parties have created programs that are demeaning, confusing, and demoralizing to their beneficiaries, leading to the deep and grounded skepticism of government that Deepak heard from his students.

But there is another factor we want to highlight to help explain this disconnect—a dramatic cultural turn that has been weaponized by the authoritarian right and neglected by the technocratic, policy-obsessed left.

The Rising Wave of Unhappiness

Happiness, measured in a variety of ways, has been on the decline for decades in the United States, and this phenomenon is crucial to understanding the cultural sources of the authoritarian turn. The meaning of “happiness” is of course contested, slippery, and culturally specific. We’re using the term here deliberately because it is a frame through which people understand their everyday lives. But we’re not using the word to describe ephemeral, moment-to-moment feeling states. We use “happiness” to refer both to objective indicators of well-being and to people’s subjective characterizations of their satisfaction with their lives.

Since 1990, the number of Americans reporting they feel “not too happy” has been trending upward, particularly among those without a college education. The onset of the pandemic only exacerbated the growing national unhappiness: By 2021, just 19 percent of Americans reported that they felt “very happy”—the lowest level on record since the General Social Survey began asking the question in 1972. The intensifying unhappiness is also reflected in data showing that more and more Americans are overdosing on drugs and that the suicide rate has increased by about 30 percent over the last couple of decades. Our culture and politics are increasingly driven by this rising wave of unhappiness.

And it’s a worldwide phenomenon. Gallup data reveal a global surge in unhappiness that predates the pandemic and has gotten worse since. The percentage of people reporting a negative overall experience of life increased nearly by half around the world between 2011 and 2021—from 24 percent to 33 percent. Surprisingly, this trend coincides with a steady decline in the global poverty rate over at least the last couple of decades.

But although happiness in the United States has fallen on average, there are profound differences across demographic groups. One of those divides is class. Since 1990, a growing gap in life expectancy has emerged between the one-third of the country with college degrees and the two-thirds without, driven in part by “deaths of despair” from drug overdoses, suicide, and alcohol-related liver disease. Class-based discrepancies in happiness have long been present in the United States, but researchers have found that the “happiness gap”—the divide between those with the lowest socioeconomic status and the highest—has steadily grown between the 1970s and the 2010s.And this dynamic, too, is not the same for all groups. White Americans appear to be losing ground in terms of happiness compared to their Black counterparts, despite persistent racial inequities. College-educated whites with high incomes experienced stable happiness levels or slight declines, but white Americans without a college degree saw a 28 percent drop in happiness from the 1970s to the mid-2010s. By contrast, working-class Black Americans without college degrees experienced relatively stable happiness levels throughout the four decades, and higher-income, college-educated Black Americans experienced large gains, with 63 percent more Black adults with a college degree reporting they were “very happy” in the mid-2010s compared to the 1970s.

These differences present a paradox: Those in relatively privileged positions, such as white men, are experiencing greater declines in happiness than groups facing objectively worse social conditions. One explanation for this is that white Americans, particularly white men, feel that their dominant position in the social hierarchy is diminishing, and studies have shown that status threat is associated with greater mortality among whites.

To be sure, worsening financial circumstances—for example, as evidenced by non-college-educated white men’s declining wages over recent decades—likely play some role in explaining this group’s downward trend in happiness. But economic conditions make up just one piece in the larger happiness puzzle and cannot be assessed without taking sociopsychological dynamics into account as well. For example, economist Pinghui Wu shows that between 1980 and 2019, non-college-educated men’s earnings decreased by 30 percent on average relative to the wages of all workers. But white men responded to declining wages by exiting the labor market in huge numbers, while Black and Hispanic men did not. This finding points to the way economic realities are mediated by identity, and it is suggestive of the power of people’s sense of social status to shape their economic and political decisions.

The causes of rising unhappiness are complex, but they surely have roots in the failures of a neoliberal economic regime that has fostered insecurity, isolation, anxiety, and fear—and was brought about by politicians in both political parties. Neoliberalism privatized risk, catalyzed alienation, and cultivated feelings of inadequacy and low self-worth for the 99 percent. But the fact that neoliberalism is a primary cause of unhappiness does not mean that the implementation of progressive, redistributive economic policies alone will lead to rising happiness. Bad economic policy has produced knock-on effects of increasing drug use, homelessness, and mental illness—realities that have come to dominate the mental landscape of voters who nonetheless may not see economic policy as a source of solutions. There are many other related causes contributing to the unhappiness wave, including corporate social media, the impending sense of doom brought about by the climate crisis, and the social and cultural aspects of neoliberalism such as the dramatic decline of people’s attachment to institutions like work, unions, and churches. Loneliness and social isolation are major drivers of unhappiness. We are experiencing a crisis of what French sociologist Émile Durkheim called “anomie,” or normlessness, arising from the dizzying pace of social, economic, political, and technological change in our times and the weakening of institutions that foster social cohesion.

How Authoritarians Surf the Unhappiness Wave

Whatever the causes, it turns out that unhappiness is a very strong predictor of voting behavior. Being extremely unhappy more than doubled a person’s likelihood of voting for Trump in 2016, and the unhappiest counties were the Trumpiest. As social scientist Johannes Eichstaedt and colleagues show, “Unhappiness predicted the Trump vote better than race, income levels, or unemployment, how many immigrants had moved into the county, or how old or religious the citizens were. Unhappiness also predicted the Trump election better than other subjective variables, like how people thought the economy was going or would be going in the future.”

Other researchers have shown that counties that went to Trump were often “landscapes of despair,” characterized by more economic distress, poor health, low educational attainment, high alcohol and suicide mortality rates, and high divorce rates. States with the lowest life expectancies and education levels used to vote strongly for Democrats, but the past four decades have witnessed what Nobel laureate Angus Deaton called an “extraordinary realignment,” with those states now heavily favoring the Republican Party.

MAGA extremists have made the most of the cultural turn, capitalizing on the unhappiness wave for political gain. Trumpist politicians invoke righteous indignation not only about material economic conditions, but also perceived disrespect by cultural elites, rising crime, and disintegration of traditional family structures. The power of this story derives partly from its clarity about the enemies—despised “others”—and from the sense of community and shared purpose that participation in the mass authoritarian project provides. There is considerable evidence that authoritarianism is driven by racial animus. Whether supporters view it this way or not, the MAGA movement is fundamentally a white supremacist movement that activates racist beliefs as a powerful political weapon. Despite the common narrative that Trump’s 2016 win could be explained by the economic distress of Americans who felt they’d been left behind, research shows that candidate preference was influenced more by issues that threatened many white Americans’ sense of dominant group status.

The emotional alchemy of the authoritarian approach is so strong that it can override facts and material reality. Trump duped millions with his false claim to have brought back manufacturing jobs. (In reality, manufacturing jobs declined during his Administration.) By contrast, Biden’s success in reducing unemployment to the lowest level in 54 years goes virtually uncredited, with his approval rating hitting an all-time low of 36 percent this past May. In the same poll, an astounding 54 percent of Americans said that Trump handled the economy better than Biden has so far, compared to just 36 percent of Americans who felt the opposite was true. The MAGA extremist response succeeds because it speaks to a visceral sense of dissatisfaction and promises security, belonging, and recognition.

It works because it offers a kind of psychic release, an outlet for powerful emotions to find expression. There is an angry ecstasy in authoritarian rallies and online culture. MAGA extremism takes seriously some aspects of people’s actual, lived experience (like a sense of bewildering change and threatened life prospects), and it invents other threats (like trans people, immigrants, refugees, and racial justice protestors). If anomie or normlessness is the problem, authoritarianism supplies certainty and a compass to navigate a changing world.

Importantly, authoritarianism does not depend on solving people’s problems to succeed politically; indeed, its genius is to harness and feast on unhappiness without trying to reduce it. In his speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference in March, Trump spoke openly to this pain and offered the satisfaction of revenge: “In 2016, I declared, ‘I am your voice.’ Today, I add: I am your warrior. I am your justice. And for those who have been wronged and betrayed: I am your retribution.”

This challenge will not be solved, as the Biden Administration seems to be realizing, by industrial policy or progressive economic policy alone. Although the wave of unhappiness is partly the result of neoliberalism, the cultural response has acquired its own force and exercises a powerful influence on social identities and modes of living, thought, and feeling. People who do not conceive of their unhappiness as a product of economic forces and seek solutions in other spheres of life are unlikely to be moved by an economistic response, however worthy it may be and even if they agree with specific policies. Biden has spent much of his political capital in his first term on delivering economic wins, while deprioritizing issues like racial justice, voting rights, immigration reform, and reproductive rights that have a deeper connection with people’s most salient identities. But his reelection campaign’s pivot toward defending personal freedoms and denouncing MAGA extremism signals a recognition that deliverism is not a viable political strategy.

Implications for the Fight Against Authoritarianism

What does the death of deliverism mean for progressive strategy? We see four strategies that are crucial to countering authoritarianism; all involve broadening our idea of how to talk to people and taking seriously fears and anxieties that we have too often tended to ignore or downplay.

First, progressive policymaking must take identity, emotion, and story much more seriously. We should care not only about the details of the policies we pass, but also about how we fight for them. Policies that deliver economic benefit without speaking to, reinforcing, and constructing a social identity are likely to have little political impact. Progressives won a victory for working people in passing the expanded child tax credit, but leading up to, during, and after passage they largely failed to tell a political story that answered urgent questions: Why was this happening? Who were the beneficiaries? And why did they deserve to get the check? An exception was Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, who defended the fact that people without earnings got the child credit by saying, “raising kids is work.” That’s a compelling moral argument that draws on and amplifies the powerful identity of parenthood. But most who promoted the policy failed to make that case. So even though the economic, material benefit of the expanded child tax credit was enormous, the political benefit was close to zero.

Contrast this with “Build the Wall,” Trump’s only partly realized signature policy proposal that had zero economic benefit but activated intense (if not broad) support by tapping into a social identity—whiteness—and telling a story, complete with villains and heroes, of being under siege. As historian Greg Grandin has written, “The point isn’t to actually build ‘the wall’ but to constantly announce the building of the wall.”

Progressive policymaking will need to better identify and make clear for people the culprits fueling our discontents. Stories without villains make no sense to anyone. The mainstream Democratic Party’s tendency to avoid naming corporations as bad actors, whether pharmaceutical companies or big banks, is politically disastrous. The Bernie Sanders campaigns showed the importance and potential of telling a simple, true story about cause and effect.

Second, progressives must offer ideas about issues they have too long neglected. Economic changes may be at the root of what ails us, but they are refracted through people’s lived experience with things like violence, addiction, mental health problems, social isolation, loneliness, and a sense of social disintegration. Progressive policymaking and political rhetoric have been extraordinarily thin on these topics, tending to treat them as secondary issues. The visceral experience of class, race, and gender is often felt through these non-economic aspects of life.

People’s fears of crime may be exaggerated, for example, but their feelings of disorder and danger are real and demand a response. This is not just about reaching Trump voters—it’s about reaching working- and middle-class people across racial lines. Taking fears of crime seriously is not an inherently conservative position; what’s important is how policymakers address these concerns. Do we turn to outdated, cruel, and ineffective answers, like punishment and fear-mongering? Or do we tackle crime at the root, offering all people nourishment, care, and community? It’s time we realize that people aren’t foolishly “voting against their interests,” as many on the left have long argued and struggled to explain. People hold multiple and sometimes contradictory identities and interests. It’s not inevitable which identities or interests will come to the fore and determine their political allegiances. We have to take seriously people’s preoccupations as they define them, not as some distraction from what they should care about.

Some of the root causes of growing unhappiness aren’t solely economic and need more attention. Social media, for example. Utah is the first state to have restricted access to social media without parental consent for those under 18. The idea raises concerns—for example, some kids, particularly queer and trans youth, may find solace in supportive relationships built on the internet, especially if they find themselves in homophobic or transphobic in-person environments (which is increasingly likely in states, like Utah, that have banned gender-affirming care). But the Utah law is an actual response to the impact tech companies are having on our brains, especially young brains. As digital media use has increased, in-person social interactions, amount of sleep, and general happiness have plummeted among teens. The CDC reports that the percentage of teenage girls who said they feel persistently sad or hopeless increased from 36 percent in 2011 to 57 percent in 2021. Nearly one in three had seriously considered attempting suicide—up nearly 60 percent from a decade ago. Progressives need to confront these issues with the seriousness they warrant and offer clear solutions.

We also need to take social connection, isolation, and community much more seriously as policy priorities. Even before COVID-19 changed the way we interact with our social worlds, three in five Americans were classified as lonely. Research shows that Americans’ number of close friendships has shrunk over the past few decades, especially for men: In 1990, just 3 percent of men reported having no close friends at all, but by 2021 that number had risen dramatically to 15 percent. Policy can’t solve a crisis of friendship directly—but it can support the rebuilding of social institutions, like community organizations and unions, that create opportunities for connection. (There is considerable evidence that unions are a bulwark against authoritarianism.)

Third, progressives need to articulate not just a string of worthy policies, but a vision of the good life grounded in what British cultural theorist Stuart Hall called “root ideas” about how we should live, who we should care about, and what makes for a meaningful life. Neoliberal striver culture promises wealth, security, and pleasurable consumption through individual effort. This conception of the good life has proved persuasive to people across race and class lines. An ethno-nationalist, patriarchal vision promises community, belonging, and status dominance through the support of authoritarian leaders. That vision has gained adherents as fewer people find the promise of striver culture to be convincing. A compelling alternative progressive vision will start from first premises about identity, purpose, and the grounds for human flourishing, and will make practical sense to people grappling with everyday challenges by providing clear stories, complete with heroes and villains.

Fourth and most importantly, reinvigorated organizing and recruitment of new people, especially working-class people, into worker and community organizations is essential. But the craft of organizing has been in deep decline. As long-time community organizer Kirk Noden puts it, “Never have there been so many people with the job title ‘organizer,’ never have so many foundations funded organizing, and never has there been so little real organizing happening in America.” People are often mobilized on issues but too rarely invited to be part of a democratic community built on relationships that forge collective power.

There is important innovation underway. A new generation of organizing efforts in both blue urban and red rural terrain pairs work on issues with a strong emphasis on building community and connection, including sometimes through direct services and mutual aid. Make the Road NY, a grassroots organization rooted in immigrant communities, uses services to recruit working-class immigrants and actively constructs a culture of belonging grounded in love that forges strong ties. While the organization delivers concrete benefits to community members, people who seek services first experience an “agitational intake”—a conversation that situates a personal problem in a collective context and asks individuals to join with their neighbors to fight for structural solutions. People may come for the service, but they stay for the community. Political scientist Deva Woodly shows how the Movement for Black Lives has developed a politics of care and specific practices, like healing justice, that connect personal pain and trauma to collective struggle.

Defanging authoritarianism requires a shift in organizing methods to widen the on-ramps that welcome in people who are not already progressive and to work at the levels of survival needs, meaning, and identity—not only policy. One group, Hoosier Action in Indiana, likes to say that its model is to create an organization that is a “Church, Shelter, and Vanguard,” meaning that it provides a combination of belonging, mutual aid, and intensive training and meaning-making. The organization also works directly on issues at the heart of the crisis of despair, like the opioid epidemic. Hoosier Action is building community-owned centers that can provide an institutional home to help foster solidarity among working-class people. Some organizing on the right—for example, in evangelical churches—is thick in this same way, forging deep social ties rather than relating to people transactionally on issues of the moment.

Organizing works in part because it breathes life into latent social identities. For example, someone may be a worker, but that may not become their primary identity until they are engaged in a concrete struggle over wages and benefits with other workers. The students receiving the refundable child tax credit experienced having something done to them, rather than being protagonists in the story. And the latent and powerful identity of being parents, with the deep love that lies at the core of their purpose, was untapped by the policy debate. Progressive efforts to implement the Inflation Reduction Act are far more likely to increase civic engagement if they proceed from an organizing, rather than a technocratic, mindset.

The Cloth and the Milk

In a series of classic behavioral experiments conducted in the mid-twentieth century, psychologist Harry Harlow separated infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers and placed them in isolation, where they had access to two surrogate “mothers” fashioned by Harlow. One surrogate mother was constructed out of wire and offered milk from a feeding tube; the other wore soft terry cloth but did not provide milk or food. The infant monkeys showed a strong preference for the cloth mother, spending far more time clinging to it and running to it when frightened. When hungry, they would go to the wire mother, but then immediately return to the comfort of the cloth mother. At times, the monkeys would even try to reach their lips to the feeding tube of the wire mother while still grasping onto the cloth mother. Progressives have, too often, played the role of the wire monkey, expecting love in exchange for benefits that are vital but insufficient.

Deliverism is not the solution to our democracy crisis because, as Staci K. Haines has argued, our needs for safety, belonging, and dignity are fundamental to our humanity. Delivery of even dramatically more progressive economic policies than are on offer in the United States today won’t prevent the rise of authoritarianism. The rise of far-right parties in the Scandinavian social democracies—which have social and economic policies that U.S. progressives envy—is a cautionary tale about the limits of an economistic approach. The best strategy, therefore, will combine the milk with the cloth—the material with the emotional.

Solving the authoritarianism challenge requires a progressive program and organizing strategy that speak directly and persuasively to the wave of unhappiness and despair and are rooted in the texture of everyday life—what people actually talk about, care about, and worry about. Such an approach will continue to foreground economic security and rights, but it must also affirm other aspects of human flourishing that have long been emphasized by diverse social movements, including the importance of collective care, community, belonging, and solidarity. The task for progressives at this historical juncture is not to find the magic message or to deliver more popular policies. Rather, it is to offer a compelling, energizing, persuasive vision of the good life and to organize mass-based organizations through which people shape and live out those values in the here and now.

Deepak Bhargava is a senior fellow at the Roosevelt Institute and a Distinguished Lecturer at the CUNY School of Labor and Urban Studies.

Shahrzad Shams is the program manager for the Race and Democracy program at the Roosevelt Institute.

Harry Hanbury is a documentary filmmaker and journalist.

Spread the word