Smith College Professor Loretta Ross and 22nd Century Initiative Director Scot Nakagawa have both engaged for decades in the fight against the far Right. In this conversation they look at the lessons that Ross’ work with the National Anti-Klan Network hold for the present; how the landscape of the Right has changed; and how we should orient ourselves to the present. Convergence Editorial Board member Marcy Rein edited the transcript of their hour-plus dialogue.

Scot Nakagawa: Loretta, I think of you as one of the architects of the framework that is being used by social justice advocates and democracy reformers through the work you did with the National Anti-Klan Network and even earlier. Could you talk a bit about that history and what lessons you draw from it, and not just from the successes but from the mistakes you made?

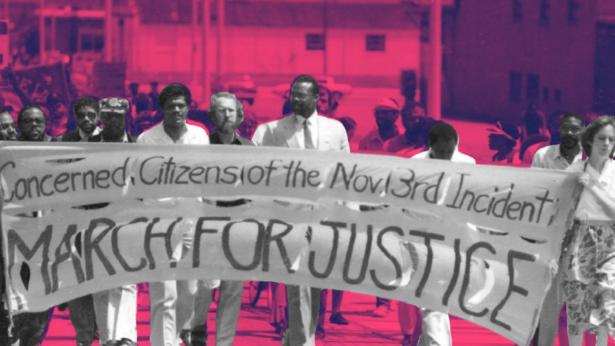

Loretta Ross: The National Anti-Klan Network (NAKN, later renamed the Center for Democratic Renewal) dates back to the Greensboro massacre of November 1979 in which five anti-Klan protestors were murdered. An interracial group of people, including Rev. C.T. Vivian, Anne Braden, Rev. Mac Charles Jones, and others, decided that there needed to be a watchdog agency, a civil rights organization that kept its eye on hate groups. The popular conversation at the time was that during the presidency of Jimmy Carter the Klan was in retreat and hate groups didn’t matter. Every time there’s a Democratic president, somebody wants to spin that narrative. But these organizers begged to differ — particularly because the people caught on videotape murdering those leftists were all acquitted, and it turned out that the FBI and the local sheriff had provocateurs in the crowd in amongst the Klansmen.

NAKN’s purpose was to monitor and report on hate groups and the threat that they posed — the Klan and what then was revealed as the neo-Nazi movement. When I came on as program director in 1990, my particular responsibilities were to help communities and individuals deal with the consequences of the far Right’s activities. If they marched through a town or committed a hate crime or whatever, my job was to parachute in and help local people come up with an effective response. We wrote a handbook called When Hate Groups Come to Town, giving people what we found to be effective responses.

We also wrote a number of smaller pamphlets about dealing with homophobia and talking about the intersection of white supremacy and law enforcement. The latter was called “They Don’t All Wear Sheets.” Three years into my term, I became the program/research director after the research director, Leonard Zeskind, received a MacArthur “genius” grant and retired. That meant dealing with a bunch of people who infiltrated hate groups and reported on them. That allowed me to do a weekly report of what hate activity occurred and what hate crimes happened, those kinds of things, and to try to plot the trajectory of their future activities. I was the only Black person and the only woman at the time managing such an opposition research department.

One of the things that I’m rather proud of was our 1994 report called “Women’s Watch.” There was such increasing violence against abortion clinics and everybody else who was running a research department at an anti-hate monitoring group was denying the overlap between the anti-abortion violence and the racist and anti-Semitic violence. I believe that they were the same people because the tactics were too similar and some of the same people we monitored in racist activities were showing up at anti-abortion protests. Others were saying, “They’re borrowing tactics from the white supremacist movement,” and I’m saying, “No, they are part of the white supremacist movement; they don’t have to borrow anything.”

In terms of mistakes, I guess the most obvious mistake would be not anticipating the prevalence of white supremacist ideology in the religious Right. That wasn’t something that we were particularly monitoring. And it’s something that Political Research Associates took on: Jean Hardisty, Chip Berlet, and Fred Clarkson recognized it and spent a lot of time monitoring the religious right and their shift to the hard right. But at CDR, we did not focus on that.

The Right makes its connections

SN: You also did mention how the far Right, the white supremacist Right, and the Christian nationalists appear to be merging. But that wasn’t as evident way back then, right?

LR: Not in the ‘70s. That was still the beginning of the Reagan Revolution. And what they badly named the Moral Majority started deciding to become much more highly political, entering into electoral politics, and that happened with the organization of Ronald Reagan’s campaign during Carter’s administration.

SN: It seems to me like NAKN, because it had the base it had (rooted in the Civil Rights Movement), did something really important in publishing for their membership. Things like the publication Mab Segrest authored, “Quarantines and AIDS” –– which came out right on time at the height of the AIDS pandemic –– had a powerful effect in helping people to see how different groups were connected to each other. It showed how the attack on gay men’s sexuality was related to the attack on abortion and affirmative action, all the different things that we were seeing playing out in that period. I felt like the Network played a really critical role in helping us who were members of it to pick up those threads and to start to see what was happening locally in a much bigger context.

LR: Of course. I don’t know about you, but my jaw dropped when I read Nancy McLean’s Democracy In Chains, and then realized that this many-headed hydra we’ve been fighting had congealed in the 1950s, and here we are 70 years later just catching up to that level of coordination while we’re playing Whack-a-Mole with all these different issues, and they have intersected these issues long before we knew the role of the Koch brothers and all of that. So it really does feel like we’re often playing Whack-a-Mole, when in fact they have a court date and cogent plan for deforming or deconstructing democracy.

SN: In 1991 we had Russ Bellant’s Old Nazis, the New Right and the Republican Party; there were all the publications by Political Research Associates… We’ve been getting these warnings for so long. Why do you think we haven’t responded?

LR: Well, part of it is capacity. Every time there’s a Democrat in office, we end up with all the foundations de-prioritizing the anti-fascist work and then they have to ramp it up all over again when a Republican gets elected. We could point out at least a dozen organizations that have folded because of this yo-yo funding. Now we’re down to three. It’s not a little foundation world thing: It’s all the white liberal perception. They are so eager to put white supremacy, the ideology, behind them that they want to declare it prematurely dead over and over again.

SN: That is such a good way of putting it. So the way that I remember this history is that in 1979 the Greensboro massacre happens. That’s an important inflection point. By the 1980s, there’s a Northwest imperative when the white supremacist movement starts to rebrand itself and move organizers and resources into the Pacific Northwest, pivoting toward youth organizing through neo-Nazi organizing and to white nationalism. Strategic realignment, basically.

To try to build a new constituency, they come up to the Northwest. The murder of Mulugeta Seraw happens in 1988. And then we learned that Muguleta Seraw’s murderers were actually connected to a national organization. They weren’t just local racist skinheads: They were connected to the White Aryan Resistance which was headed by a former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard named Tom Metzger. And that was the opening for the Southern Poverty Law Center to come in and sue on behalf of the Seraw family, because there was an entity you could sue that did collaborate with them and encourage them and train them. And that lawsuit was successful. Then there are other somewhat successful efforts to try to unseat them.

But the backdrop of all of this is FBI overreach at Ruby Ridge, in Waco, Texas, targeting the white separatist movement and what was becoming white nationalism. Then the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing happens in retaliation for those violent overreaches. And the movement is forced underground. They get put to the top of the FBI watch list and are forced to start to reorganize themselves as an underground movement. Many people think that once they were underground they disappeared.

Then we start to view the issues as more national: We start to be less concerned about the grassroots Christian nationalist movement because the election of George W. Bush mainstreams them. That precipitates this huge defunding of an entire sector of organizations that were the watchdogs, that did the vigilance work, and also organized communities to try to create a permanent countervailing force against what we thought was a permanent right-wing insurgency.

But then Barack Obama is elected president and the movement starts to explode in number in these online spaces until Donald Trump comes in and runs against the phantom Black president who can’t run again and calls the white supremacists into action as he starts to realize the power of being a disrupter. All those things seem to be leading to the present moment.

LR: Absolutely. And there would be one other thing that I would add to that brilliant analysis and that’s the role that the Aryan Nations played, and Richard Butler because of the unifying gatherings he offered. At one time the Klan and the Nazis didn’t speak to each other because there were too many former World War II people in the Klan who fought Nazis and didn’t see them as their natural allies. Richard Butler played a significant role in bringing the Klan and the Nazis together including the Church of the Creator people (COTC) led by William Pierce (author of the Turner Diaries that influenced Timothy McVeigh to blow up the Oklahoma federal building) and others who really worked hard to build unity within the white supremacist movement, just like they tried to do with Charlottesville in 2017.

SN: Yes. Now we’re facing a really sad set of circumstances. And I think you’re right about that liberalism –– at least as an ideology in the United States –– insulated people from the sense of what was actually happening. They kept thinking about us as facing an outside invading force as opposed to something endemic.

Stop fighting each other and build power

LR: Exactly. One of the sayings we have in the civil rights movement (which I always feel a little silly about quoting because I’ve never actually been in the civil rights movement — the closest work I did was the National Anti-Klan Network, and in the years before that, I was in the women’s movement) but anyway, we say that we have to convince people today that they are not the entire chain of freedom. The chain of freedom stretches back toward your ancestors and forward toward your descendants. Your job today is to make sure the chain doesn’t break at your link. That’s all you need to focus on: Not letting the chain break at your link.

SN: Speaking of the present and those of us who are attending to our links, what are your key recommendations for now? What do you think this long history taught us? What are we going to be doing?

LR: Mobilize, mobilize. That’s one reason that I’m so passionate about the calling-in culture, because it’s a well-known truism that the Republicans organize for power and Democrats organize to fight each other. I want to keep us from fighting each other so we can make sure we get the power necessary to keep the Republicans out of office and quash this neo-Nazi threat.

I live in Georgia and I want to call this “Stacey land.” Because we are where the states can be tipped blue. With Governor Brian Kemp, we know what it feels like to have the fucker who’s the referee of the election run for office. The only way Republicans stay in power in our state is by cheating. We don’t need a blue wave. We need a blue tsunami! It’s not just enough to go to the polls yourself. You got to bring 10 people. Everybody you talk to, whether it’s a grocery clerk bagging your groceries or some random taxi driver, you ask everyone if they are going to vote. We must include this in our everyday conversations. That’s what Stacey has done for us in Georgia; politics is never just a casual thing. It is a movement, a participatory democracy movement, that we’re building in this state. For every election. That’s the dominant conversation, at least in the Black community.

But I was really impressed with the last elections we had, not only 2020 but 2022 as well. Of course, the governor shut down polling precincts all through the Black community for various spurious reasons to suppress our votes. But when I came back to Georgia to vote in 2022, I couldn’t even find a place to vote because the lines were wrapped around the fucking buildings almost three times. I mean, we’re talking about massive lines as if people were giving away money. I don’t know if you’ve ever lived in a state where you experienced that. It’s amazing what that does to your spirit and your determination.

When I finally found a place where I could vote with a shorter waiting period, that line was half-white. I’m in the heart of the black community here, right? I’m not in safe, white, North Atlanta. I’m in the ghetto part of the Black community with hip-hop music blasting, people with their pants hanging off their asses, and all kinds of chicken wings being sold. And half the voting line is white. And they were patiently determined. I said to myself, “Oh my, oh, here. We got this. We got this!” You know, I so wish every state felt like the Black community in Georgia when it comes to voting.

Proven, potential and problematic allies

SN: You’re going to be at our conference. What’s your message?

LR: Calling in. I think that’s what the Left most needs to hear right now.

I mean, if I hear another young person telling me, “This is performative,” I want to stop them. If you see somebody put up a Black Lives Matter sign, and that’s all you see of them, you already know the most important thing you need to know about them, because a Klansman never put up a Black Lives Matter sign! Do your damn threat assessments better.

We’ve got three different kinds of allies: potential, problematic and proven. They all have the most important word in there: ally. But we need different strategies for potential ones, for problematic ones and for proven ones. Because we’ve got to unite all of them against the actual fascists. But if we dismiss people because they’re problematic or unproven, then we weaken our own forces. And if we missed the potential of the Black Lives Matter sign person, we’ve shot ourselves in the foot.

In the civil rights movement, they used to say we need to turn to each other instead of on each other. If you read the accounts of Ralph David Abernathy, Joseph Lowery, and C.T. Vivian, Hosea Williams, and all these other people, they used to fight so bitterly behind closed doors, but they knew how to present a united front once they came out to confront Bull Connor. The legends have it that even the Selma march that John Lewis organized, most of the leaders didn’t want him to do it. But you never heard a word of criticism about him doing it. And so that’s what we need to learn. You don’t win when you’re trying to be right, versus trying to be effective. That’s gonna be the big message.

Convergence is pleased to co-publish this article with The Forge.

Loretta J. Ross is a visiting professor at Smith College. In the course of her decades of activism, Loretta became one of the first African American women to direct a rape crisis center; served as the program/research coordinator at the Center For Democratic Renewal (National Anti-Klan Network) and the national coordinator for the SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Justice Network.

Scot Nakagawa is a co-founder and co-director of the 22nd Century Initiative, a national strategy and action hub in the fight to defeat white nationalism and authoritarianism. Scot is also the founder of The Anti-Authoritarian Playbook, an online newsletter to the frontline of the growing movement to win a truly people-centered, pluralistic, multiracial and feminist democracy in the U.S.

Convergence is a magazine for radical insights. We work with organizers and activists on the frontlines of today’s most pressing struggles to produce articles, videos and podcasts that sharpen our collective practice, lift up stories from the grassroots, and promote strategic debate. Our goal is to create the shared strategy needed to change our society and the world. Our community of readers, viewers, and content producers are united in our purpose: winning multi-racial democracy and a radically democratic economy.

Today, our movements continue to grow, but so too does the threat from the racist, authoritarian right. We believe we can defeat them, dismantle racial capitalism, and win the change we need by building a new governing majority that is driven by a convergence of grassroots social movements, labor movements, socialists, and progressives. Join us.

Spread the word