A few hundred million years ago, when rocks and water ruled the world, the Appalachian Mountains rose out of a shallow sea. Humans came much later, the first appearing in the region just twelve thousand years ago, and have always had to creatively accommodate its ancient geology. Today the roads of Appalachia snake and coil, making mystifying designs through the stubborn mountains. Appalachia and its people are governed by a turbulent history.

Documentary filmmaker Elaine McMillion Sheldon’s family has been in Nicholas County, West Virginia for eight generations, living in the same hollow on Fenwick Mountain since the turn of the twentieth century. The story goes that their ancestors arrived on foot from Wise County, Virginia, about 150 miles southwest as the crow flies. But the crow can fly over mountains, and Central Appalachia is an almost impassable area on land. As for how they made the journey, Sheldon says, “Aunt Ola reckons they just followed a river.”

Sheldon has made two films about the opioid crisis in her native state: Heroin(e), which garnered her an Academy Award nomination, and Recovery Boys. She’s also worked with PBS Frontline a few times, and been nominated for half a dozen Emmys, winning two. Hollow, her first film out of film school, picked up a Peabody Award in 2013, and she received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2020. That same year she released Tutwiler, documenting how America’s prison system handles pregnant incarcerated women and their newborns.

I meet Sheldon at a Walmart parking lot in Summersville, the Nicholas County seat. She is pregnant with her second child, and has kindly offered to show me around the region and talk about her new film, King Coal, an intimate and philosophical look at Appalachia’s socioeconomic relationship to its central resource.

She’s also a coal miner’s granddaughter. We ride from Summersville to nearby Nettie to see her grandfather Doy Russell, one of the on-screen stars of King Coal, whom she calls Paw Paw. Russell retired from the mines in ’86. Today, at eighty-eight years old, he digs graves for five funeral homes in Nicholas County, as well as for family and friends. He’s dug four generations of his family’s graves, from his mother to his wives to his great niece. There is an exquisite symbolism in Russell’s transition from miner to gravedigger, for in many ways the film feels like a requiem for coal. It asks: What exactly do we do when the king dies and there is no clear heir apparent?

“I’d been influenced by these historical records of grieving and mourning,” Sheldon says. “The film is not trying to prescribe a solution to post-coal. It’s more: What is the next step that allows a new mindset to enter? We haven’t faced the fact that we are standing on the other side of decline with no real direction. So grieving felt like the first natural step in that.”

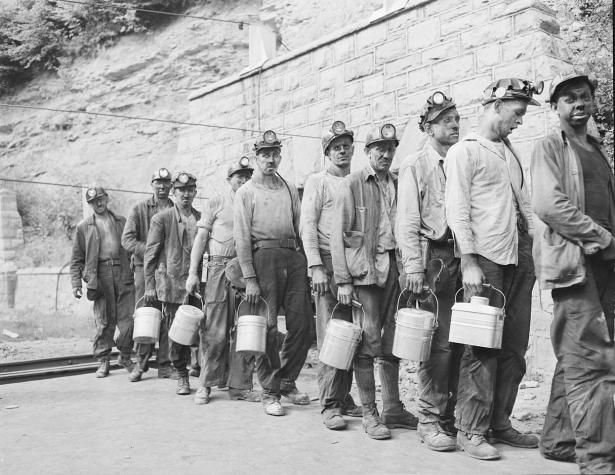

As we pull into Russell’s, we see him on his front porch with his wife, Nancy, wearing the work blues that he still dons every day. He sits back in his rocking chair and starts telling us stories from his mining days with a clear memory of and reverence for the past. His career spanned coal’s critical transition from “hand-loading” to the more automated methods that have transformed the industry and its workforce. We listen to him talk about the union, the company, and his complex, often contradictory feelings about them both.

Then he shows me the simple records he keeps of the graves he digs: name, date, and price, all handwritten on the back of old union ballots and mining guidelines.

Sheldon looks sincerely across the porch and says, “Paw Paw, one of the reasons I made the film was because you once told me everything that’s gone the way it’s gone didn’t have to go this way. That part of the reason these communities have been hollowed out and people have had to leave and there’s nothing left for people here is because of greed.”

Russell rocks and nods in agreement. “Everything in Nicholas County that should be for the people here they ship off and make big bucks off it. I’m a full believer in the man up above and when they started hollering about the rights to the minerals and everything I prayed about it. And He let me to know that we had everything we need as long as the earth stood, but it’s who was in charge of it.”

He walks us into the yard to show off a big pile of coal that to this day he shovels into a stove to heat his home. Then we inspect his heavy gravedigging machinery in a shed close by. “Some people charge as much as nine hundred dollars to dig a grave. I won’t do that. I don’t think it’s fair to the people,” he says.

After we leave Russell’s house, Sheldon and I stop for lunch at Lora’s Family Restaurant, where our waitress is another coal miner’s daughter. Over white beans and cornbread, we talk about the mine as a kind of embodied monster. “Even the mine has been named like a giant,” Sheldon says. “You enter the mouth. You mine the face. It has ribs that you hold up.” The colossal mine has the power to make people smaller or bigger, to swallow them up or to blow them out of proportion. “The early ballads about coal are full of myths and coal miners being larger than life.”

Fred Powers talks to kids at White Hall Elementary in West Virginia about his time in the mines. (Courtesy of the filmmaker)

But King Coal is not a nostalgic film about sitting on a porch with an old miner listening to stories. In fact, Paw Paw Doy doesn’t even speak when he’s on screen. Sheldon is conscious that the myths of her grandfather’s generation are not resonating in the same way with younger people. Part of her aim with the film is to focus on the kids, the intergenerational aspect of Appalachian mythmaking.

“When you center a kid rather than a bunch of elders you start thinking about what is left for them. Kids were immediately relevant to the film because there’s miners going in classrooms telling them stories. Kids are being indoctrinated so early but they are given a story they don’t own. The kids in the film break down the level of importance that adults here put on coal.”

Ancient forests canopy our drive up the mountain, until suddenly sunshine blights the scenery. The earth stands scorched-looking and bare — a huge swath of land has been clearcut, an unsustainable logging practice that is common despite local protests.

“I don’t think that healthy people can live on unhealthy land,” Sheldon says. “For my Paw Paw’s generation, before coal companies owned all the land, the commons was a very important idea. There’s land that we all hunt on, that we all care for.”

The Matter of Ownership

We veer off of Fenwick Mountain and down into her family’s hollow. Houses of various shapes and sizes are scattered across the green grass. We park in front of one to find Aunt Ola and Uncle Fred sitting on the front porch. They greet their grandniece with pleasure and usher us inside to see Great Uncle Roy. At ninety-six, Roy’s vision is poor, but he smiles wide at the sight of Sheldon approaching. Sheldon takes after Roy’s creativity. Rarely seen at family functions without a camera around his neck, Roy is a photographer, painter, and family chronicler, and was the only artist in the family while Sheldon was growing up.

I ask about the family’s journey on foot from Wise, Virginia down into this hollow. As Aunt Ola tells it, Roy and Doy’s uncles were sent by their mother to Nicholas County because she heard that there was work in logging. Mining was taking off around Wise, and she didn’t want her boys working in the mines. The uncles did manage to find work in timber, but before long the allure of the coalfields was unavoidable. Sheldon recounts how Doy’s decision to enter the mines had been influenced by the look of the loggers’ missing fingers.

Outside, a teenager rides around on a four-wheeler chased by a huge German shepherd. A pile of coal sits in front of a shed. A goat and pony mingle about a pasture. The land is pristine, homely, and theirs.

But beneath the ground is another story. The rights to the minerals of much of West Virginia were separated long ago from surface rights to the land. The deeds to these deals were done a hundred years ago and passed down through the generations, making it hard to tell who owns what. Sheldon’s family has never owned the mineral rights in the hollow. Around the middle of the twentieth century Crichton Mines, the employer of several of her uncles, got underneath the family property and took the coal.

“My great grandma couldn’t use her well,” Sheldon says. “The underground mine sunk it. They had to buy water fifty cents a gallon to have it to drink, but they used the spring for everything else. Eventually city water came on the mountain in 1978.”

We ride to Richwood, the nearby town where most of Sheldon’s family was schooled. On the way a hitchhiker stands smiling, sure to be picked up, maybe even recognized, by a local traveler. Richwood is nestled deep in a small valley. You get the feeling that standing smack in the middle of it you can reach your arms out in either direction and touch the sides of the mountains. Its geography left it vulnerable to catastrophic flooding in 2016. The plot of land where the high school once stood is now vacant, razed to the ground after the flood.

On Main Street we enter Rosewood Florist, a local shop run by Sheldon’s cousin Jeromy Rose and his wife Christy. Beyond flowers the shop sells a variety of goods and houses a café with locally roasted coffee beans. We sit at the counter and Rose, a coal miner’s son and sometime location scout for Sheldon’s work, talks about the political fight that went down when it was decided that the Richwood schools damaged in the flood would be demolished and not rebuilt, in favor of an educational amalgamation in Summersville half an hour away. The community fought back, and the case went to West Virginia’s Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Richwood.

I ask Rose about the political energy within the community to organize against the Summersville school plans and whether that same energy exists around other issues, such as mining. “I hate politics,” he says, before proceeding to speak politically and passionately for fifteen minutes. “But coal companies own the mines. And people view the schools as theirs. They’re community assets paid for by our tax dollars. We were outraged. All you had to do was post something on the Richwood Facebook page and people would show up in droves.”

When he was twenty-six, Rose ran for mayor of Richwood and won. Having gone to art school, he decided to commission a series of massive murals, which now stretch across the sides of buildings on Main Street and showcase the vivid history of Richwood. The public art withstood the flood, reminding the residents of their collective past as they organized themselves to fight the school closure.

“You cannot recover from something like a natural disaster if your schools are taken from you,” Rose says. “Over time we’ve lost our hospital, our armory. We were tired of losing things.”

New Myths

From Richwood we cross the county line and make toward Fayetteville. The town is seeing a bit of a tourism boom due to the adjacent New River Gorge National Park, the country’s newest national park signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2020. We ride over what once was the longest single arch bridge in the world, now trailing four in China. Nine hundred feet above the New River, we look down on the dense trees, competing for space and sunlight as the Appalachian spring turns to summer.

Dinner is at the home of Dina Hornbaker, a musician and activist who now works in solar energy. Around the table are also Katey Lauer, a community organizer, and Crystal Good, the independent publisher of West Virginia’s only black media publication, Black By God. Hornbaker has taken some mushrooms from her garden and made a risotto, and Lauer has spun a salad out of homegrown kale and beets. All three women appear in King Coal and are working across disciplines to help reshape Appalachia’s self-conception.

“What the Trump election really showed was that coal is our identity,” says Good. “And when you take away someone’s identity and you don’t have anything to replace it with you are creating panic and chaos. So if we are not a coal miner, who are we?”

“One piece of the story that gets missed about mining identity, and the film plays with this,” says Lauer, is that “it used to be that the primary identity around mining was the union. ‘I’m a union member. I’m a union man. We’re a union family.’ And [coal baron] Don Blankenship and company had a deliberate strategy to break the unions that involved an awareness that identity mattered.”

Lauer refers to Friends of Coal, a pro-industry group set up in response to hits the industry was taking from environmental activists in the early aughts. It has since become a ubiquitous catchphrase in Appalachia, used to deter criticism of the coal industry and consolidate the culture around the coal mythos.

“We are not that special,” says Good. “Yes, I am Appalachian and I wear it, but really we are just like any other place in the world that has had an extraction economy. We are not unique. But people have to rally around jobs or identity. So the work with the narrative I am trying to build around black folks in Appalachia is something people can see as part of the greater consciousness of black America, rather than separate from it.”

The women discuss the merit of the myths they’ve inherited around organizing. Lauer recounts her time working for a campaign in the 2020 governor’s race that attempted to build a broader movement rather than organize around their political candidate’s identity. Hornbaker explicates different ways to identify with the land, other than through the mines. Good talks about the harmful values she’s inherited from Appalachian working-class culture around the virtue of working yourself to the bone. Sheldon watches her friends with pride, letting them speak at length.

Lauer sighs and says, “There’s this illusion that a $30,000 grant is going to solve the underpinning of the problem.”

“Or learning to code!” says Hornbaker.

“I think we will find more answers if we are humble enough to name the depth of how difficult the problem is.” says Lauer. “Policy and foundation leaders push this simple solution and there’s some arrogance about that.”

“Things like King Coal are important for the spirit,” says Good. “Our soul is suffering because we’ve been told we are proud coal miners but now we don’t have coal.”

Pineapple is served for dessert. “It’s local!” jokes Sheldon, who bought it from Walmart. We sit across from each other. As in Sheldon’s film, the complexity of the problem is respected at this table. But through local food and fellowship, the way forward becomes clearer. If Appalachia’s past has been dominated by a monoeconomy and a monopoly on myth, it will no doubt need an interdisciplinary approach in reorganizing its future — changing the way people relate to work, local natural resources, and the past.

Most of all, the future is a matter of resource ownership. Like Doy Russell said, “We have everything we need . . . it’s just who’s in charge of it.” Will Appalachia be owned by anonymous corporate entities that strip it for parts, or by the people who live on, love, and often nurture the land?

Each shot of King Coal, on which Sheldon’s husband served as the director of photography, is composed with a painterly regard. Sheldon’s voiceover provides a poetic commentary that makes room for contemplation. The viewer understands that there is not just coal, the by-products of ancient geologic movement and compression, in these mountains. There are people here, too, living rich and meaningful lives amid the region’s radical changes.

“I found an old notebook trying to remember what I was doing with this film,” says Sheldon. “I had asked myself if documenting joy is as valuable as documenting pain. I was like, I can’t make another film that is going to make people feel paralyzed. There has to be joy. I know the film is hard for people, but I feel there is still hope in it.”

King Coal opens in New York City August 11 at the DCTV Firehouse. The following week the film will release in select cities. For tickets and information visit kingcoalfilm.com/screenings.

Chandler Dandridge is an American psychotherapist and educator. His clinical interests revolve around addiction, anxiety, and exploring creative ways to improve public mental health.

Our new issue on the 20th anniversary of the Iraq War is out now. Subscribe today for just $20 to get it in print!

Spread the word