Donald Trump Wants Coal Mining Jobs To Be a Big Election Issue and It Seems the Washington Post Is Prepared To Help

As a major proponent of global warming, Donald Trump apparently thinks it benefits him to be perceived as a savior of jobs in the coal industry. This is likely not because he can do much to protect the country’s remaining coal jobs, but it gives him an opportunity to appear to be supporting workers.

The Washington Post, which is owned and controlled by people who will pay lower taxes with Donald Trump back in the White House, seems anxious to help Trump in this effort. That is the most likely explanation for the article near the top of the home page on how the Democrats are facing problems in a coal county in Pennsylvania.

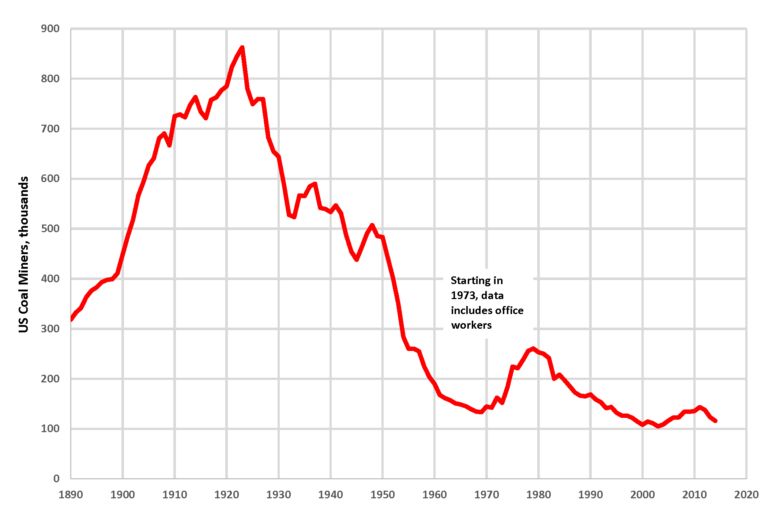

Before dealing with the specifics of the article, some background on coal and coal mining jobs is needed. The coal industry used to be a huge employer, both in Pennsylvania and across the country, as shown below.

Coal Industry Employment Since 1890

Source: US Census via Wikimedia.

At its peak in the middle of the 1920s, there were more than 850,000 people employed in coal mining. This was a time when total non farm employment was around 30 million, which means that coal mining would have accounted for roughly 2.8 percent of all jobs in the country.

Employment in the industry fell sharply over the next four decades, as oil and gas heating replaced coal to a large extent, and productivity growth reduced the need for miners. By the late 1960s, we were down to around 130,000 jobs in the coal industry, meaning we had lost over 700,000 jobs. At that point, total non farm employment was over 70 million, so the coal industry accounted for a bit less than 0.2 percent of total employment.

There was an uptick in employment in the industry in the 1970s, as the OPEC price increases led people to switch back to coal. Employment in the industry peaked at roughly 260,000 in 1979.

Employment in the industry then fell sharply over the next 20 years, sitting at just over 100,000 by 2000. The major factor was productivity growth, as strip mining replaced underground mining and also a switch back to oil and gas as their price fell back from the 1970s levels. Pollution regulation was also a factor in this decline, but a less important one. We were producing 50 percent more coal in 2000 than we had in 1979.

In the last dozen years, employment in the industry again fell sharply as natural gas displaced coal in many electric power plants. Currently, employment stands at a bit over 40,000, which is slightly less than 0.03 percent of total employment.

It’s clear that the general direction of employment in the coal industry is downward. Solar and wind power are already cheaper in most circumstances, with the costs declining rapidly. The cost of battery storage is also declining rapidly. Unless we impose massive taxes on clean energy and/or have huge subsidies for coal, we will be using much less coal in the years ahead.

This means that we will lose most or all of these 40,000 jobs in the not distant future. The question is, how big a deal is this?

Let’s say we lose the jobs over the course of a decade. That comes to 4,000 jobs a year. By comparison, in a healthy economy, 1,600,000 workers are laid off or fired from their jobs every month. This means that the 4,000 or so coal mining jobs we can expect to lose over the course of a year are less than one-tenth the number of people who would be losing their jobs in a typical day.

To be clear, the fact that lots of other people are losing their jobs doesn’t mean the job loss is any less traumatic for these coal miners. In many cases, this will be the best job they can ever hope to get. And in some small towns, the coal mine will be the main employer, so its loss will devastate the community. That is not something to be trivialized.

But we do need to keep it in perspective. Between 2000 and 2007 (before the Great Recession) we lost 3.5 million manufacturing jobs, largely due to trade. This far more massive loss of jobs (roughly 100 times as many) seemed to get less attention from the WaPo and other media outlets than the coal mining jobs now at risk.

Even taking this WaPo piece at face value, it’s difficult to see much of a case for its story. Pennsylvania is widely recognized as a swing state and a small number of votes can make a difference, but we should be clear on how small the number at stake here is likely to be.

Pennsylvania has 4,700 coal mining jobs as of May. Total employment in the state was 6.15 million, which means that the industry accounted for less than 0.08 percent of statewide employment.

The counties where coal is important are overwhelmingly white. Indiana County, which is the focus of the article is roughly 95 percent non-Hispanic white. Trump carried the rural white vote in 2020 by margins of close to two to one even in areas like rural Minnesota and Wisconsin, where the coal industry has never been an issue. That means that if Biden can somehow overcome anger over coal jobs, he would still likely lose these voters by a large margin.

Suppose that every coal mining job is associated with two votes and if Biden can somehow do the right thing by the miners (in their view) it will reduce Biden’s losing margin among this group by 10 percentage points. That would translate into 940 additional votes for Biden. This is almost certainly a large exaggeration of what is plausibly at stake since many of these people will not vote and 10 percentage points would be a very large shift.

In 2020, Biden’s margin of victory in the state was 1.2 percentage points or 80,000 votes. In this context, the 940 votes plausibly at issue in coal country could matter, but it’s not likely.

What could have a much greater effect is if the Washington Post and other major media outlets can keep up a drumbeat that Biden is indifferent to the plight of ordinary workers. That is how this article is best understood.

Dean Baker is Senior Economist and co-founder CEPR in 1999. His areas of research include housing and macroeconomics, intellectual property, Social Security, Medicare and European labor markets. He is the author of several books, including Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. His blog, “Beat the Press,” provides commentary on economic reporting. He received his B.A. from Swarthmore College and his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Michigan.

His analyses have appeared in many major publications, including the Atlantic Monthly, the Washington Post, the London Financial Times, and the New York Daily News.

Dean has written several books including Getting Back to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People (with Jared Bernstein, Center for Economic and Policy Research 2013), The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive (Center for Economic and Policy Research 2011), Taking Economics Seriously (MIT Press 2010) which thinks through what we might gain if we took the ideological blinders off of basic economic principles; and False Profits: Recovering from the Bubble Economy (PoliPoint Press 2010) about what caused — and how to fix — the current economic crisis. In 2009, he wrote Plunder and Blunder: The Rise and Fall of the Bubble Economy (PoliPoint Press), which chronicled the growth and collapse of the stock and housing bubbles and explained how policy blunders and greed led to the catastrophic — but completely predictable — market meltdowns. He also wrote a chapter (“From Financial Crisis to Opportunity”) in Thinking Big: Progressive Ideas for a New Era (Progressive Ideas Network 2009). His previous books include The United States Since 1980 (Cambridge University Press 2007); The Conservative Nanny State: How the Wealthy Use the Government to Stay Rich and Get Richer (Center for Economic and Policy Research 2006), and Social Security: The Phony Crisis (with Mark Weisbrot, University of Chicago Press 1999). His book Getting Prices Right: The Debate Over the Consumer Price Index (editor, M.E. Sharpe 1997) was a winner of a Choice Book Award as one of the outstanding academic books of the year.

Dean previously worked as a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute and an assistant professor at Bucknell University. He has also worked as a consultant for the World Bank, the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress, and the OECD’s Trade Union Advisory Council. He was the author of the weekly online commentary on economic reporting, the Economic Reporting Review (ERR), from 1996–2006.

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) was established in 1999 to promote democratic debate on the most important economic and social issues that affect people’s lives. In order for citizens to effectively exercise their voices in a democracy, they should be informed about the problems and choices that they face. CEPR is committed to presenting issues in an accurate and understandable manner, so that the public is better prepared to choose among the various policy options.

Toward this end, CEPR conducts both professional research and public education. The professional research is oriented towards filling important gaps in the understanding of particular economic and social problems, or the impact of specific policies. The public education portion of CEPR’s mission is to present the findings of professional research, both by CEPR and others, in a manner that allows broad segments of the public to know exactly what is at stake in major policy debates. An informed public should be able to choose policies that lead to improving quality of life, both for people within the United States and around the world.

CEPR was co-founded by economists Dean Baker and Mark Weisbrot. Our Advisory Board includes Nobel Laureate economists Robert Solow and Joseph Stiglitz; Janet Gornick, Professor at the CUNY Graduate School and Director of the Luxembourg Income Study; and Richard Freeman, Professor of Economics at Harvard University.

Spread the word