In this special section, co-sponsored by The Indypendent and the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung New York Office, we delve into the landscape of the New York City movement in solidarity with Chile in the tumultuous aftermath of the Sept. 11, 1973, coup that saw the overthrow of President Salvador Allende’s democratically elected government and the rise of General Augusto Pinochet’s oppressive dictatorship. Fifty years later, we honor the sacrifices and draw inspiration from the enduring legacy of New York’s solidarity actors in their pursuit of justice and democracy amid one of Chile’s darkest chapters.

The global movement standing in unity with Chile initially surfaced while Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular democratic socialist government (1970–1973) was in power. The UP’s victory in the 1970 presidential election and Allende’s unwavering commitment to forging a democratic path toward socialism garnered substantial attention and empathy worldwide. The government’s imperative to build a more equitable society led by the working class served as inspiration for countless individuals beyond Chile’s borders during the short period of Allende’s administration.

The news of the military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet on Sept. 11, 1973, sent shockwaves across the world. The oppressive Pinochet dictatorship, which subjected thousands of Chileans to torture, murder, and disappearance, ignited international resistance to his illegitimate government. Standing in support of the Chilean people, New Yorkers felt compelled to respond. Amid the upheaval and repression in Chile, New York City became one of the centers for exiled Chileans seeking safety and support. Various solidarity initiatives blossomed throughout the city. Leftists, artists and exiles emerged in this context as key protagonists in a multifaceted movement that sought to amplify the voices of those suffering in Chile and challenge the human rights abuses perpetrated by the Pinochet regime.

The solidarity movement with the Chilean people also played a crucial role in enlightening Americans about the extent of U.S. imperialism’s influence in Latin America. These groups exposed the immoral strategies employed by the U.S. government and corporations to safeguard their economic and political interests and the consequences of U.S. interference in foreign governments.

This special section looks into these New York’s networks and the pivotal role they played in raising awareness. As we uncover stories of solidarity in action, we witness how the boundaries of nationality, language and culture dissolved, and a profound sense of interconnectedness took root. New York’s response to the Chilean coup epitomized the true spirit of internationalism, showcasing the power of collective action in advocating justice on a global scale.

Solidarity Initiatives

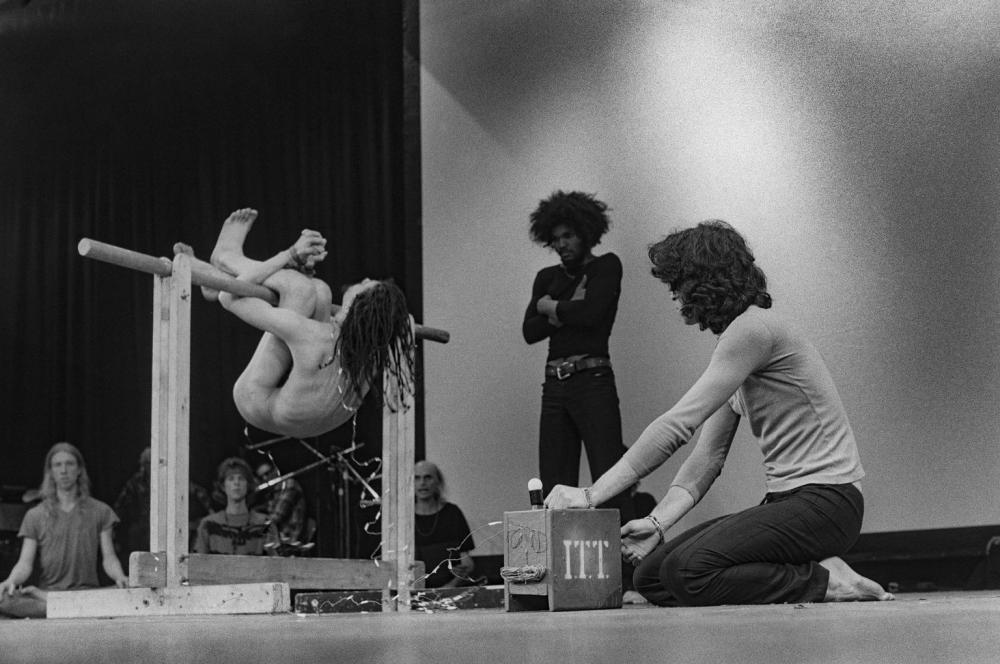

Julian Beck and Judith Malina’s Living Theatre reenact torture on stage at An Evening with Salvador Allende, organized by Phil Ochs with Friends of Chile, Felt Forum at Madison Square Garden, New York, May 9, 1974.

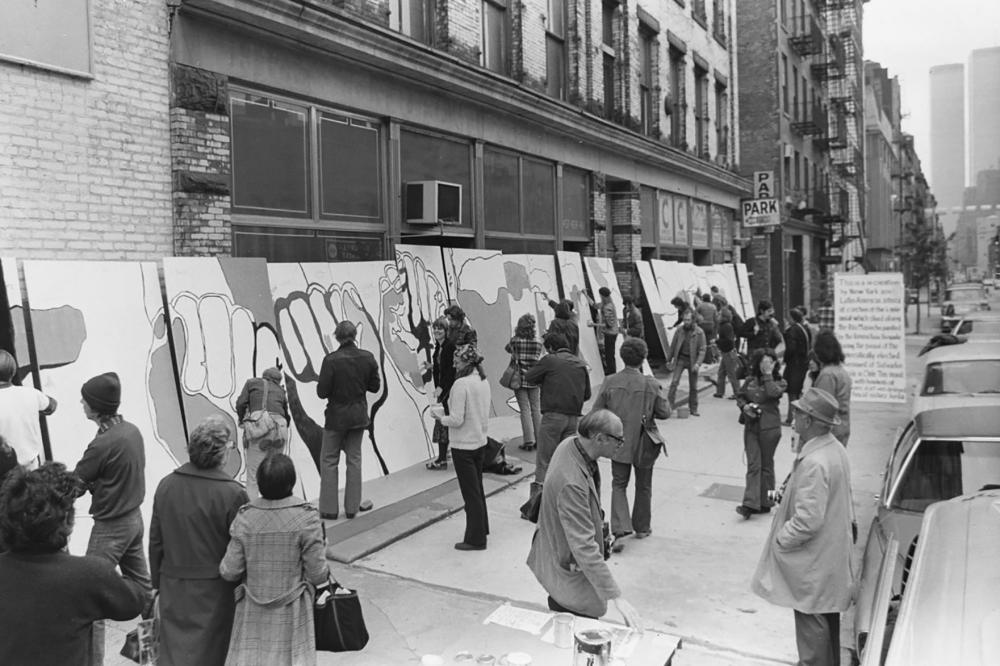

On October 20, 1973, New Yorkers gathered on West Broadway between Houston and Prince St. to recreate a 100-foot-long political mural in Chile that was destroyed by the military regime.

AN EVENING WITH ALLENDE CONCERT

The Friends of Chile, An Evening With Salvador Allende Benefit Concert, on May 11, 1974, was one of the main international acts in support of Chilean exiles, the first to attempt to rally global rejection of the established dictatorship in the country, and the first to openly criticize and confront the intervention of the U.S. government in the military coup that had overthrown Salvador Allende a year earlier.

The event, held at Madison Square Garden, was organized by U.S. protest singer Phil Ochs and Chilean actor and poet Claudio Badal. Ochs, motivated by his interest in Latin American political processes, had visited Chile in 1971 to closely experience the labor and university movements. A close friend and admirer of popular Chilean communist singer, poet, and actor Víctor Jara, Ochs was moved to organize the benefit concert after the Pinochet regime kidnapped, tortured, and executed Jara in the aftermath of the coup.

The evening featured an eclectic and wide-ranging lineup with Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Dennis Hopper, Bob Dylan, Swedish diplomat Harald Edelstam, Gato Barbieri, and others. Allende’s widow, Hortensia Bussi, was also at the venue. The Living Theater, an American experimental theater company, staged a vivid reenactment of the tortures described by former prisoners of the Brazilian dictatorship (1964–1985), which was also devastating that South American country at the time.

MURALS FOR THE PEOPLE

Cover of Eva S. and James D. Cockcroft, “Murals for the People of Chile,” in Toward Revolutionary Art, no. 4 (1973): 2-11. Lucy R. Lippard papers, 1930s– 2007, bulk 1960–1990.

A leaflet made without computer software urges people to come out for the Oct. 20 mural action.

The final step in the mural making came on Oct. 27 when the panels were presented to representatives of the Chilean National Airlines.

Following the 1973 coup, a group of intellectuals, artists and other cultural workers organized a solidarity initiative to replicate a mural originally created by the Brigada Ramona Parra (BRP) in New York. The original mural had been destroyed by the dictatorship upon taking power.

BRP was a muralist brigade associated with the Chilean Communist Party. Established in Chile in 1968, the BRP was responsible for producing murals in various public spaces throughout the country, conveying social and political messages. Following Pinochet’s coup, the regime launched a concerted effort to eliminate all forms of leftist art and culture, which included the whitewashing and erasure of BRP murals.

In a show of solidarity with Chile’s resistance movement, a group that included important figures of New York’s cultural scene, such as art critic Lucy Lippard, art historian Jaqueline Barnitz, exiled filmmaker Jaime Barrios, and Chilean artist Enrique Castro-Cid, issued a call to join a protest against “censorship, book- and art-burning, and the arrest of artists and intellectuals in Chile.” Organized under the name Concerned Artists from the US and Latin America, the group invited New Yorkers to recreate a 100-foot-long mural that had been destroyed by the regime. This mural, originally located at the Mapocho River in Chile, was reproduced on West Broadway between Houston and Prince Street.

ARTISTS FOR CHILE

Orlando Letelier was a Chilean economist, politician and diplomat. In 1971, he was appointed ambassador to the United States by Salvador Allende. Back in Chile in 1973, Letelier assumed various key roles within the government. After the coup, he was swiftly apprehended by the military authorities. He was among the initial members of the Allende administration to be detained and subsequently incarcerated in a political prison. During his year-long captivity, he endured imprisonment in different concentration camps and was subjected to torture.

After mounting international diplomatic pressure that included the mediation of the governments of Venezuela and the U.S., the regime agreed to release him on condition that he leave the country. Forced into exile, Letelier moved to the U.S. and took an academic post in Washington, D.C. There he became a fellow of the Institute for Policy Studies.

On September 21, 1976, Letelier was killed in a car bombing in Washington in a politically motivated assassination orchestrated by agents of the Chilean military regime. The bomb was planted in his car, and upon detonation, Letelier and his IPS colleague Ronni Moffitt were tragically killed. Even beyond Chilean borders, Pinochet’s regime demonstrated the lengths it was willing to take to suppress opposition.

After his assassination, a group of artists from the US Ad Hoc Committee of the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia “Salvador Allende” organ-ized an art exhibition and benefit event at Cayman Gallery in New York for the “Chile Committee for Human Rights” in memory of Letelier, showcasing artworks from American and Latin American artists.

Nitza Tufiño, Nuyorican artist, co-founder of El Museo del Barrio and member of the political-artistic collective Taller Boricua, was one of its organizers.

THE ESMERALDA SHIP PROTESTS

Critics of the Chilean regime protested the presence of the Esmeralda in the bicentennial parade of ships on July 4, 1976.

The boat was previously used as a site to torture political prisoners.

The protest against the Esmeralda was held at Pier 86 on Manhattan’s West Side where the “torture boat” was docked.

The Chilean naval ship “Esmeralda” was slated to participate in the July 4th Bicentennial parade of tall sailing ships on the Hudson River in 1976. The vessel had previously been highlighted in a report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights of the Organization of American States as a floating detention facility where political prisoners were subject to torture by electric shock, beatings and high-pressure water hoses.

“The four-masted barquentine Esmeralda, Chile's envoy to Operation Sail, has become the object of protests here by groups charging that political prisoners were tortured aboard the ship," The New York Times reported.

"There would be good reason to protest any Chilean ship coming here,” Susan Borenstein of the National Coordinating Center in Solidarity with Chile told The Times. “Its presence would make a mockery of the very principles of democracy and human decency our nation is celebrating in this Bicentennial year.”

According to The Times, Action for Women in Chile, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), Amnesty International, religious groups and others expressed their opposition to this symbol of the Chilean military regime in New York City and organized a protest at Pier 86 on Manhattan’s West Side. The National Council of Churches submitted a draft resolution to the New York City Council calling on Mayor Abe Beame to deny access to the ship to any city-owned facility.

— The New York Times: ‘Four Master From Chile Is Called Torture Ship’ June 20, 1976. ‘Fete for Chilean Naval Ship Faces Protest’ June 26, 1976.

VELADAS POLÍTICAS

Part of the audience at the Velada (evening) dedicated to Pedro Lastra, organized by the Pablo Neruda Cultural Center at the loft of Marcelo Montealegre and Silvia Doris Dillems Quezada, SoHo, New York, 1979.

Chilean photographer Marcelo Montealegre has been living in New York City since 1968. In the aftermath of the coup, Montealegre joined the movement denouncing Pinochet’s dictatorship in the city and documented a large part of the political and artistic activities that took place in that context.

By the end of the 1970s, along with other Chilean artists such as filmmaker Javier Barrios (who arrived in NYC in 1977), he began organizing monthly meetings at his loft in Soho, nicknamed Veladas (evenings). In these gatherings, recent exiles and activists shared and discussed news about the current situation in Chile. They called the space the Pablo Neruda Cultural Center.

As the news of the activity started reaching other groups, Nicaraguans, Salvadorians, Argentinians, and other Latin American exiles joined the meetings, eventually transforming them into a political and art center for Latin American solidarity in New York City.

SOURCES:

— Iglesias Lukin, Aimé. This Must be the Place: An Oral History of Latin American Artists in New York, 1965-1975. New York: Americas Society/ISLAA, 2022.

—Power, Margaret. “The U.S. Movement in Solidarity with Chile in the 1970s.” Latin American Perspectives, vol. 36, no. 6, 2009.

—The New York Times Archives

Research & text by Mariana Fernández

Spread the word