The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and the Warrantless Collection of Personal Data

Introduction

Spying has been a practice of the U.S. government since its inception. Gathering intelligence is justified because it helps uncover malicious actions that could endanger the safety of Americans and people around the world. However, in many instances intelligence is gathered unlawfully on individuals who have no harmful intentions and in violation of Americans’ Fourth Amendment right to privacy. This explainer breaks down the various illegal spying practices the U.S. conducts and the reforms needed to ensure constitutional integrity.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) sets the rules for the collection of foreign intelligence by the U.S. government, including critical rules that protect or compromise Americans' privacy. It first became law in 1978, but since then, it has been amended multiple times to enable greater domestic surveillance.

Section 702

Section 702 of FISA was enacted in 2008. It allows intelligence agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the National Security Agency (NSA), and the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), to search through billions of warrantlessly acquired international communications. These agencies target non-U.S. persons (meaning non-U.S. citizens or residents) outside the U.S. and compel electronic communications companies, such as Google and Verizon, to turn over these individuals’ communications. Because we live in a globalized world, many Americans’ Fourth Amendment-protected conversations are swept up “incidentally.” This information includes emails, text messages, and internet data. In 2013, 89,138 individuals were targeted under Section 702 (Figure 1). In 2022, 246,073 people were targeted. Hundreds of millions of communications continue to be collected each year.

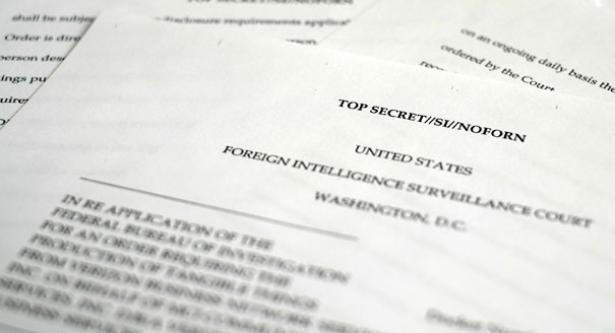

Figure 1

Reformers have focused on the CIA, FBI, NSA, and NCTC’s practice of knowingly searching through this staggering amount of warrantless surveillance, specifically looking for information about U.S. persons (U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents) who are protected from illegal surveillance, even when located abroad. U.S. Privacy advocates call this the "backdoor search loophole." In 2022, intelligence agencies conducted over 200,000 of these “backdoor searches.” The FISA Court revealed that the FBI engaged in “persistent and widespread” violations when conducting these backdoor searches.

The Section 702 database has been used to search the communications of:

-

A sitting Member of Congress and a sitting Senator.

-

141 Black Lives Matter protesters.

-

19,000 individuals who donated to congressional campaigns.

-

Individuals whom eyewitnesses called “tips” on because they were of “Middle Eastern” descent.

-

A state court judge who reported civil rights violations to the FBI.

Despite Section 702’s stated use for foreign intelligence, it has become a tool of domestic surveillance and led to repeated violations by the intelligence community and misuse of Fourth Amendment-protected private communications. Section 702 is set to expire on December 31, 2023. Reauthorizing it provides Congress an opportunity to reform these unconstitutional practices. Because Section 702 certifications are issued annually, current surveillance practices will continue until April 10, 2024, even if Congress does not act.

Other Surveillance Practices

In addition to Section 702, other surveillance practices lead to the warrantless collection of Americans’ private data.

Executive Order 12333

Executive Order (EO) 12333 allows the government to spy on foreign individuals, organizations, and other entities abroad. Like Section 702, this inevitably collects private information on Americans, given our interconnected world. This means there are similar backdoor searches conducted under EO 12333 as under Section 702. The CIA operates bulk collection programs under EO 12333, which includes gathering Americans’ financial transactions and other private information.

Data-Broker Loophole

The Data-Broker Loophole allows the U.S. government to purchase Fourth Amendment-protected data, such as phone call records, internet activity, location information, and other electronic data, directly from data brokers, which are third parties that harvest data from communications and technology companies such as Verizon, AT&T, and Meta. Congress prohibited these companies from directly selling this sensitive data to the government in the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. Additionally, the Supreme Court ruled in Carpenter v. United States that a warrant protects some of this data. However, no court is involved in authorizing or overseeing these purchases. Agencies such as the FBI, DHS (including CBP and ICE), and DOD are purchasing this data on an enormous scale.

Congress took a meaningful step to address the warrantless purchase of Americans’ data in the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act. It prevents government agencies from purchasing Americans’ data from communications and technology companies. It unanimously passed the House Judiciary Committee on July 19, 2023. House Floor consideration is pending. A companion bill has been introduced in the Senate.

Judicial Process

Three main issues exist concerning the judiciary’s role in protecting Americans’ constitutional rights against illegal government surveillance.

-

The FISA Court: The FISA Court operates in secret and generally only hears from government lawyers. The participation of other lawyers, or amici, is extremely limited, meaning there isn’t a lawyer who raises issues with or questions FISA Court proceedings or rulings. Additionally, amici don’t have access to the same information as government lawyers, making it difficult for them to appeal decisions.

-

Civil Lawsuits: Plaintiffs are required to prove definitely that the government surveilled and gathered data on them. Because foreign intelligence surveillance is conducted entirely in secret, obtaining this proof is virtually impossible. This effectively ensures that plaintiffs don’t have the standing to sue. Even if individuals can prove they have standing (i.e., they have definitive proof the government spied on them), FISA Courts could reject a case claiming it involves “state secrets.”

-

Criminal Lawsuits: The government is legally required to inform defendants in criminal cases if it intends to use evidence obtained under Section 702. However, this practice has not occurred in the past five years. To avoid providing this notice, one practice the government conducts is “parallel construction.” Agencies gather evidence by searching the Section 702 database but then go back and recreate an alternative source of the evidence to evade FISA’s notice requirement.

The Government Surveillance Reform Act

The Government Surveillance Reform Act (GSRA) is a bicameral, bipartisan bill that reforms provisions of FISA, Section 702, and other surveillance practices. Notable reforms include:

-

Closing the “backdoor search loophole” by requiring law enforcement and intelligence agencies to obtain a warrant before searching through Americans’ communications that were obtained without a warrant under Section 702 or EO 12333. There are exceptions to this, including:

-

When an agency receives consent from the individual, for instance if someone has been targeted by a foreign actor.

-

Emergencies, such as if a person’s life is at risk.

-

Cybersecurity-related searches for malware.

-

-

Closing the “data broker loophole,” meaning agencies can’t bypass Constitutional and statutory safeguards by purchasing private data directly from data brokers and would instead have to obtain court orders.

-

Providing a larger role for amici in FISA courts, such as allowing them to appeal FISA court decisions and ensure they have access to the same information as government lawyers.

-

Making it easier for individuals to have standing to sue if they believe they have been improperly surveilled.

-

Ensuring defendants in criminal cases receive notice if an agency will use information derived from Section 702.

The GSRA was introduced on November 7, 2023, by Rep. Warren Davidson (R-OH-08), Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA-18), Sen. Ron Wyden (D-OR), and Sen. Mike Lee (R-UT). While committee or floor activity has not been scheduled, the House Judiciary Committee is expected to consider the legislation soon.

On November 16, 2023, the Republican majority of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) released a report proposing legislation that fails to address the well-documented abuses of Section 702 and would also expand warrantless surveillance in several ways. One of the many concerning HPSCI provisions would allow government agencies to search through Section 702 databases for the communications of non-U.S. persons (including those legally in the U.S.) applying for a green card, visa, asylum, or other immigration benefit—with zero suspicion that they pose a threat to national security.

The GSRA would enact much-needed reforms to the government’s warrantless surveillance practices. Still, additional reforms are needed, such as narrowing the scope of non-U.S. persons the government can target. Right now, government agencies can collect data and surveil virtually anyone in the world due to FISA’s overly broad definition of “foreign intelligence.” Individuals who have no connection to malign foreign actors should not be targeted for surveillance.

Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act

On December 4, 2023, Congressman Andy Biggs (R-AZ-05) introduced the Protect Liberty and End Warrantless Surveillance Act (PLEWSA). This legislation, like the GSRA, would require government agencies to obtain a warrant before searching through Section 702 data to obtain information on U.S. persons. The PLEWSA would also reform the FISA courts and includes the Fourth Amendment Is Not For Sale Act, which would close the data-broker loophole for location and other sensitive information. The PLEWA is expected to be marked-up by the House Judiciary Committee on December 6, 2023. Bipartisan cosponsors are; Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH-04), Rep. Jerry Nadler (D-NY-12), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA-07), Rep. Warren Davidson (R-OH-08), Rep. Sara Jacobs (D-CA-51), and Rep. Russell Fry (R-SC-07).

Conclusion

While FISA serves a key purpose in helping gather intelligence on threats to people in the U.S. and around the world, many surveillance practices under FISA violate Americans’ right to privacy. The GSRA would protect Americans’ private information from warrantless collection under Section 702 and EO 12333, prevent the lawless purchase of sensitive information from data brokers, and more.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus Center thanks The Brennan Center for Justice, Demand Progress, and Electronic Privacy Information Center for their comments and insights which contributed to this explainer.

Mariam Malik,, Senior Foreign Policy Associate, joins the CPC Center from the U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on House Administration, where she assisted the committee with its work related to election administration, voting rights, and election security.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus Center brings together community leaders, researchers, movement organizations, and the public to develop people-led, cutting-edge policy ideas to address the economic inequity and systemic racism that the pandemic has laid bare.

Spread the word